“Interesting how the theatre publications picked up that Karen Olivo wasn’t returning to Moulin Rouge in LESS THAN AN HOUR. And needed to be called out into publicizing ANYTHING about the abuse that human beings suffered at the hands of Scott Rudin”, wrote the Broadway actor Eden Espinosa on Monday.

Olivo’s announcement, of course, was tied to her distress at Broadway’s silence and collusion around those revelations; but the Broadway websites were faster to report her decision to give up her Tony-nominated role than it was to report the background information that precipitated it.

Over the years, I’ve worked for — or contributed to — a lot of theatre websites. So I’ve seen from the inside how many of them work; and how frequently dysfunctional they can be. There’s sometimes inevitably a tension between their commercial interests (usually to sell tickets or offer other promotional content that producers pay for) and their providing a genuine, unbiased service to their readers.

I was in at the beginning of the launch of Broadway.com, the now biggest-branded Broadway website — a growth achieved partly because the name makes it look like it is an ‘official’ channel for Broadway, whereas in fact it is a third-party reseller of ticketing for Broadway shows, putting a considerable service charge mark-up on each ticket it sells.

Its original owners — the same people who had also secured the URL for Hollywood.com — had done so at a cost of several million dollars, knowing the value that the name would have; and when in turn the site was re-sold to others, before ending up with the John Gore Organisation, the name alone remains its biggest asset.

For Gore (pictured above), a British-born Broadway investor and producer, owning the website now is part of a vertically-integrated business model in which he now owns a distribution channel to promote the shows and sell tickets for them that he himself is involved in — his company also owns Broadway Across America, a leading producer/investor in touring shows and theatres outside New York — as well as giving him leverage over other Broadway shows, too, who need him to help sell their tickets.

Gore came after me, but I was there when Broadway.com was just an editor Kathy Henderson (who I knew because she used to edit a New York theatre magazine InTheater that I’d been the London correspondent to) and an assistant. She subsequently hired Paul Wontorek — now Editor-in-chief of the site — to join her; and then she bowed out, leaving him in charge. I remember having an awful lot of difficulty getting my invoices paid, and eventually jumped ship.

But a few years later, Paul came calling again — Broadway.com was exploring moving into the West End market, and wanted to hire contributors on the ground here. He came to me and Matt Wolf (also a London contributor to the New York Times and other publications; he’s most recently done a stint as an interim London editor for Broadwayworld. com).

The company had acquired the theatre. com URL — another New York-based site I’d once been involved in — and wanted to relaunch it as a branded West End version of Broadway.com. They even set up a London office in Fizrovia, and brought over ticketing staff and a full time editor Beth Stevens from New York.

But London is a very different model to Broadway, with ticket inventories that aren’t centralised but spread out amongst many different competing interests; and theatre.com failed to make inroads here. They soon cut their losses, and folded their West End coverage back into Broadway. com. At this point, I joined Playbill. com as their London correspondent instead.

Playbill.com was Broadway’s oldest publisher — embedded into the fabric of the New York theatregoing experience by their monopoly of the distribution of free Playbill programmes at Broadway theatres — and their website, launched by Robert Viagas, was an early adopter of the new online environment; it offered the most comprehensive news service of any site from the very beginning. But being a part of the industry, it would be careful not to tread on toes, and only publish stories that were properly validated. That much integrity was welcomed, in a world in which other sites — including Broadway.com at the time — would rush to get scoops out, whether validated or not, just to drive traffic to it.

But integrity costs too much in lost traffic. A subsequent editor at Playbill.com called Mark Peikert brought in a fresh broom, and a renewed drive for increased traffic at any cost. I once visited the office and the newsroom worked in front of massive flatscreens that revealed how many hits each story was getting. He and his news and feature editors demanded EXCLUSIVES (but also insisted they be validated, too). I was relieved when Peikert, implementing cost cutting measures, cancelled my contract so I could exit Playbill (as did Peikert a few years later, going on to edit a site designed to promote gay porn instead (https://thegaygoods.com/why-i-left-playbill-to-write-about-gay-porn/)).

Which brings me back to Scott Rudin. After the Hollywood Reporter released their blistering story on his workplace bullying two weeks ago today, the Broadway sites were slow to report it. As I previously noted here, Theatermania soon wrote a story about the “tyrannical’ geniuses” of the theatre industry, and said why the bad behaviour needs to stop — but failed to mention Rudin by name.

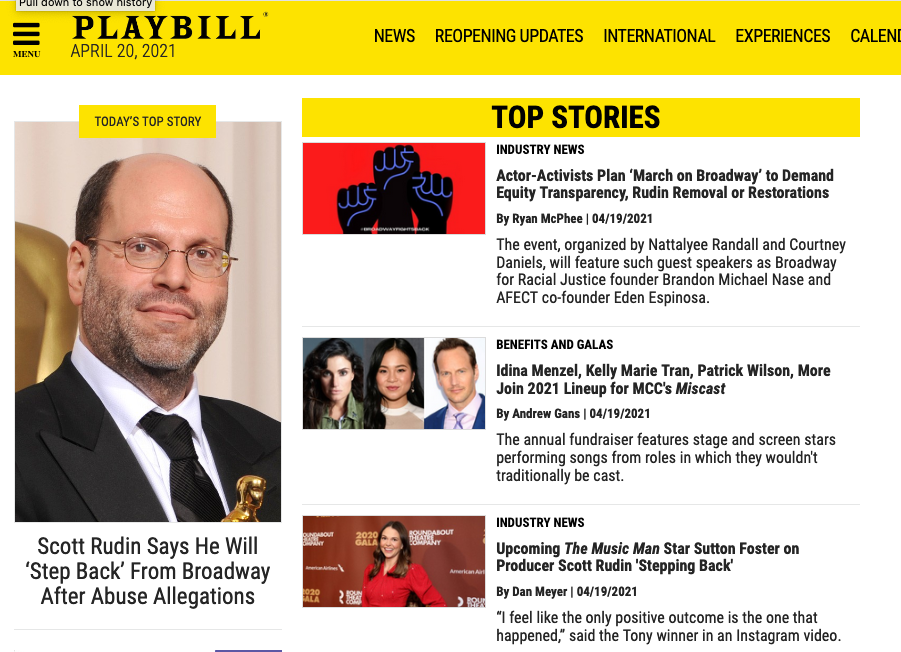

A similar timidity infected everyone from Playbill to the New York Times, both of which finally did so only after Karen Olivo pulled out of Moulin Rouge. Now the elephant in the room could finally be spoken about, as it was impacting on shows beyond Rudin’s own in a newsworthy way that couldn’t be ignored. (And Rudin stories now dominate its editorial front page, shown yesterday above).

Except that Broadway. com HAS continued to steadfastly ignore it. Go to Olivo’s profile on the site, and under related buzz, there’s still no mention of her withdrawal from Moulin Rouge.

Broadway.com is, in other words, still protecting Rudin; could it be due to wanting to protect their access to the highly valuable ticketing inventory his shows give them? His next production — the long-awaited revival of The Music Man, starring Hugh Jackman and Sutton Foster — is sure to be a hot ticket; and they want to be part of it.

The same is true of the lucrative advertising dollars that Rudin brings to the New York Times: his shows typically take full page ads all the time, and especially in the season preview Arts and Leisure section that usually appears in September, there have been occasions when his shows have occupied ten or more full pages. So no wonder the New York Times didn’t want to publish negative stories about him; who wants to kill the goose that lays golden eggs?