Vaudeville Theatre, London WC2 with Peter Capaldi/Zoë Wanamaker to July 24 at certain performances; Sheila Atim/Ivanno Jeremiah at other performances to August 1; then Omari Douglas/Russell Tovey from July 30, and Anna Maxwell Martin/Chris O’Dowd from August 6, at different performances. Pics: Marc Brenner

Nick Payne’s infinitely fascinating and multi-faceted 2012 play about the endless possibilities of life (and facing death) is perfectly expressed in a revival of director Michael Longhurst’s original production that has now been cast in four different age, race and gender combinations that itself yields multiple meanings

Critics (and audiences) are used to double and even triple theatrical bills (though it’s interesting that Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, originally conceived and premiered as a two part experience, is being scaled back go just one “highlights” play when it returns to Broadway in November, though the original six hour version will continue to play in London). But for the press ‘day’ of Constellations we were invited to see the same play twice over so we could see the first two pairings, before we are asked back to see the next two in August.

Of course, this isn’t quite the ordeal that, say, seeing Angels in America repeatedly would be (with its seven-hour plus running time), as Constellations is short, (bitter)sweet, and brisk; it runs for just 70 minutes. But it packs more of a couple’s lifetime into those 70 minutes than many a longer play, as it replays their intimate relationship, from first meeting at a summer barbecue to the passing of one of them.

It bristles with ideas about mortality and infinity, as it wrestles with whether we’re really unique or just part of a multiverse where our lives may being lived in many other combinations and outcomes, as it confronts the ultimate existential dilemma of life: “If only we could understand why it is that we’re here and what it is that we’re meant to be spend our lives doing,” says Roland, the professional bee-keeper and honey maker (his stuff is sold in the Budgens in Crouch End)

The imminence of death, of course, brings this all into perspective, as Roland’s partner Marianne — a research scientist at Sussex University– gets cancer. But as he craves more time together, she points out, “The basic laws of physics don’t have a past and a present. Time is irrelevant at the level of atoms and molecules. It’s symmetrical. We have all the time we’re always had. You’ll have all the time we’ve always had.”

This reminds me of something my brother, a veterinary surgeon, once wisely said to me after a pet rabbit of mine died: “Animals don’t measure their lives in time — only we do.” That’s the most obvious, yet also most profound, thought when it comes to grieving a beloved pet; and this play provides a similar sort of existential comfort as we wrestle with our own limited time on this planet.

We can only hope to make the best of the time we have. And seeing this production twice — or even four times — over is the best use of time I can think of in the West End right now (at least until Come from Away returns, with its similarly life-affirming message of the importance of kindness).

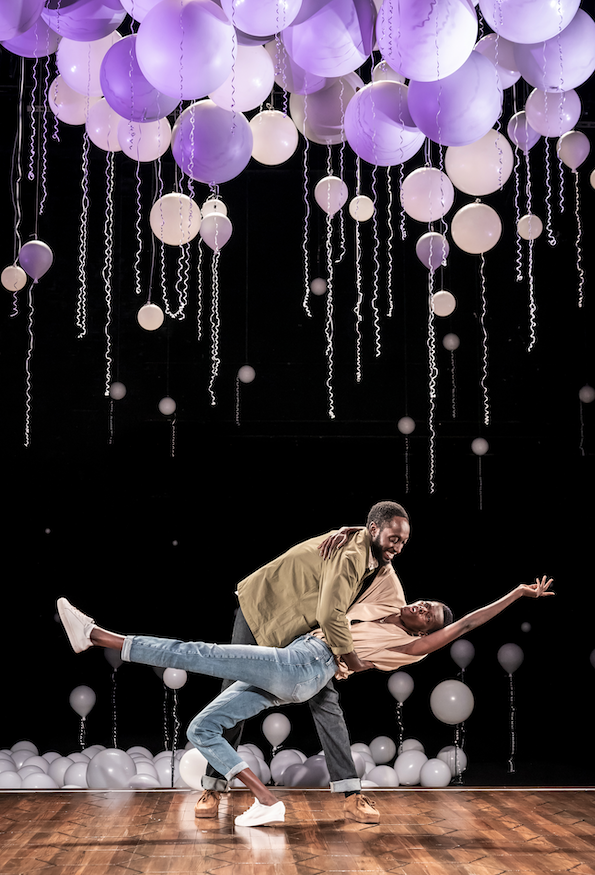

And the different couples on the first day showed how endlessly permeable and shaded our lives can be, even when we speak the same words and are undergoing the identical experiences. The first thirty-something couple, Sheila Atim and Ivanno Jeremiah (pictured above), bring an easy, youthful affability and warmth to the roles; while the older coupling of Zoë Wanamaker and Peter Capaldi (in real life, she’s currently 72 to his 63, though Wanamaker looks a lot younger; pictured below) have an edgier, more brittle rapport. They’ve just lived more. Their imminent separation by the death of one of them is no more or less cruel. (One sidebar note: I could swear, in every sense, that Wanamaker’s Marianne is more swear-y than Atim’s).

A play that is an experiment in theatrical form itself becomes a vibrant expression of it. Michael Longhurst’s exhilarating production remains an abstract, searingly beautiful wonder, with an explosion of white balloons and coloured lights onstage (the designers are Tom Scutt for set and Lee Curran for lighting) that make their own precisely choreographed contribution to a thrilling theatrical experience.