Welcome to today’s edition of ShentonSTAGE Daily, the first of 2023, and is also the first of a new monthly interview feature series.

Broadway’s latest hit show is a museum devoted to itself: the Museum of Broadway which opened its doors on west 45th Street, east of 7th Avenue, last November. The history of Broadway is, of course, being written every single night, when the curtain goes up again at one of around 40 theatres somewhere between 41st Street and 54th Street (with an occasional side trip to Lincoln Center around 10 blocks north of that). Broadway is first and foremost a living art, celebrated best in the living embodiment of it.

But some of its energy its captured in perpetuity in the wise words of its professional critics, from Brooks Atkinson and Walter Kerr (both of whom had Broadway theatres named after them, though Atkinson’s name was removed last year from the 47th Street house and replaced by that of Lena Horne) to Frank Rich, Ben Brantley and Jesse Green, the last three incumbents of the chief theatre critic chair at the New York Times. Permanent records are also made of the plays and their players in the production and celebrity photography of photographers like Martha Swope, Joan Marcus, Sara Krulwich and Bruce Glikas, amongst the many who diligently record its comings and goings.

Another constant for over 40 years was Al Hirschfeld, whose highly distinctive line drawing caricatures of Broadway accompanied the New York Times reviews of new openings. No one elevated the simple line drawing embodiment of Broadway to an art form in its own right quite as he did.

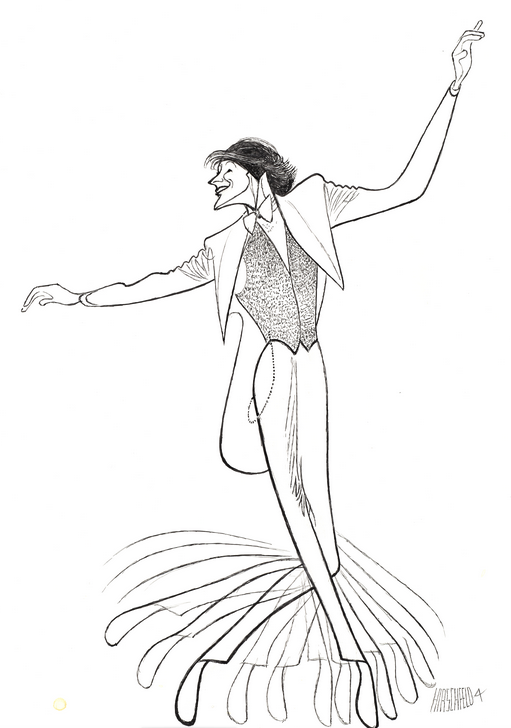

“If you want to tell the history of Broadway, you can’t do it without Hirschfeld,” says David Leopold, his professional archivist who worked alongside him for the final 13 years of his life in cataloguing his collections and establishing the Al Hirschfeld Foundation that the artist endowed to look after his legacy after his death. For over 75 years, his work was a fixture in the New York Times (and other city newspapers); his last published theatre drawing was of the great Broadway dancer and choreographer Tommy Tune, pictured above, for a show called WHITE TIE AND TAILS that ran in 2002 (pictured above).

It conveys both the apparent effortlessness of Tune’s own dance style, but also the apparent ease of drawing it: “Like Tune, Hirschfeld makes you think you can do it, too,” says Leopold. But it was harder than it looked: each picture took three to four days to complete, he goes on to explain, saying that what looks like a sweeping single line is not one pen stroke but hundreds of small scratchings. “He’d work on a hot press illustration board, scratching the lines into the board. When he inked it, it would take hundreds of small scratches to create the line, for which he’d use the same nib.”

Yet he made it look utterly unforced and without apparent effort: “He used to say that when he was rushed he’d do a complicated drawing, but when he had the time, it would be a simple one.”

He always lived in the present — for the next assignment, rather than looking to the past or his own future. “He was only ever interested in what was opening next week. That’s how you get to live to be ninety-nine and a half — by being still interested in the same things you did when you were twenty-nine and a half. The only difference was that his hair was white. But he’s had more impact on Broadway than any performer, or playwright — he was as much a part of the Broadway experience as the opening night.”

“And more people saw his drawing for THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA from when it opened in 1988 (soon to finally close on Broadway, after a run of 35 years, pictured above) than ever saw the show.”

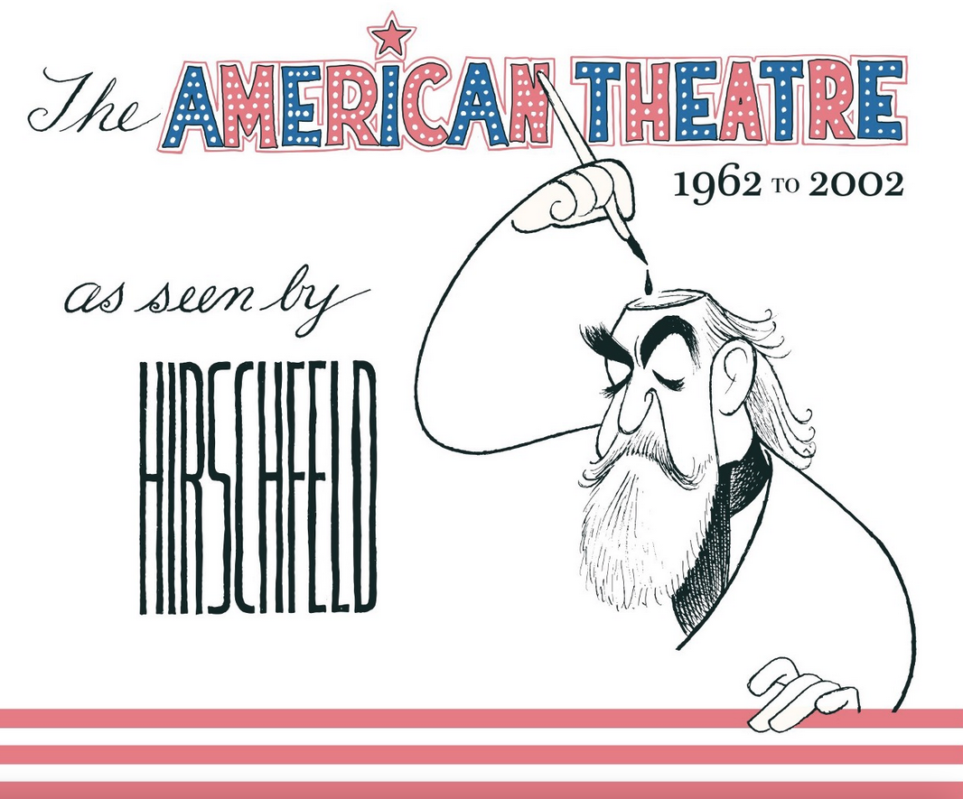

Leapold has also edited a beautiful new book THE AMERICAN THEATRE 1962 to 2002, AS SEEN BY AL HIRSCHFELD, and created a temporary exhibition of his work alongside the permanent exhibition at the Museum of Broadway; it features work from every decade of his career. “Curating is not what you put in, but what you leave out,” he says, noting, “I’ve put more pieces in the space than you would see in a traditional museum. Prepare for sensory overload when you visit it!”

And although the book and exhibition both survey his theatrical legacy, Hirschfeld also had an immense career working in film and music publicity, too. (His final film poster, appropriately, was for the film version of the play NOISES OFF in 1992). “But he was the best friend that the theatre ever had. People knew what was happening in the theatre by seeing his drawings. We don’t have anything like that anymore.”

He was a star maker, in every sense. It was seeing his caricature of Carol Channing (in a show called LEND ME AN EAR) that led composer Jule Styne and writer Anita Loos to cast her as Lorelei in GENTLEMEN PREFER BLONDES. But because he was such an affable, unassuming man, he became a beloved, trusted figure in his own right: “He drew some of the vainest people in the world, but he was greeted everywhere like an old friend.”

The ultimate accolade was bestowed on him when a Broadway theatre, formerly the Martin Beck, was re-named after him in 2003; currently home to the hit show MOULIN ROUGE, you can find an exhibition of some of his cartoons of shows that have played there in the mezzanine.

But his legacy and influence live on not just on West 45th Street but all over Broadway.

LOOKING AHEAD TO 2023

My regularly updated feature on shows in London, selected regional theatres and on Broadway is here: https://shentonstage.com/theatre-openings-from-w-c-december-19/

The next fully-updated version will be published on January 9.

See you here on Friday…

I will be back on Friday. If you can’t wait that long, I may also be found on Twitter (for the moment) here: https://twitter.com/ShentonStage/ (though not as regularly on weekends)