The Show Must Go on! is one of the oldest of theatrical adages, and it has been adopted as a rallying cry for the Theatre Support Fund, who’ve created a wonderful range of branded merchandise, including hoodies, tee-shirts (pictured below) and water bottles, to raise funds to support those affected by the current crisis, and the long theatrical shutdown we’ve endured for most of the last nine months, only briefly eased by a return to limited live outdoor performances in the summer, then indoors under limited circumstances from September. It is available to view and purchase here.

But all of those incremental green-shoots of recovery were summarily shutdown last month when Tier 3 restrictions were imposed across London and extended to other regions, too, with Tier 3 soon becoming Tier 4. As of yesterday, there’s now talk of even more restrictions on movement and socialising than are already prevented by Tier 4, with the Telegraph yesterday reporting that “some scientists have urged Boris Johnson to increase the two-meter rule, to three-meters. The scientists specifically called for a “two metres plus” rule, which would effectively increase the limit on social distancing to almost 10ft.”

Given that theatres, restaurants and shops already lobbied hard — and won — for the restriction to be limited to one-meter, plus so-called “mitigations”, going to two-meters plus mitigations would make a return to live performances come at a literally prohibitive cost.

So Andrew Lloyd Webber’s declaration to The Stage only the day before that he is, for now, sticking with his timetable to premiere Cinderella (above) at the Gillian Lynne from April 30, prior to a planned opening on May 19, seems ambitious, to say the least.

As he told The Stage, “I have taken the view, as far as Cinderella is concerned, that I am not going to change any plans at the moment. They really felt what would happen would be that January and February would be very bad, but that the combination of much better hospital treatment and the vaccine being rolled out would make things get dramatically better come the middle/end of March and that things would improve very fast. So I took my [reopening] decision based on that in November. The only thing that has changed in terms of that advice is of course the new variant of the virus, which is one thing we didn’t know then. The other thing that has possibly changed, but I hope not, is the ability to roll out the vaccine. But bearing in mind that in the middle of the summer we knew that the Oxford one was working and the timetable for that has not changed at all, my decision on everything is holding, as I do genuinely believe things will get better very quickly.”

In Stephen Sondheim’s 1973 musical masterpiece of unrequited or mismatched love A Little Night Music, there’s a great lyric:

Perpetual anticipation is good for the soul

But it’s bad for the heart.

It’s very good for practicing self-control,

It’s very good for morals, but bad for morale.

It’s very bad.

It can lead to going quite mad.

It’s very good for reserve and learning to do what one should.

It’s very good.

Perpetual anticipation’s a delicate art,

Playing a role,

Aching to start,

Keeping control

While falling apart.

And today I can’t help feeling that the total lack of clarity around where we are is leading to exactly this situation for the theatre industry: locked into a cycle of perpetual anticipation, that may be good for the soul — but very bad for the art of making theatre.

Of course theatre people are endlessly resilient — it’s an industry with so much disappointment built into it that they have to be, or they wouldn’t survive. Actors put themselves on the frontline to be judged all the time — by casting directors, by directors, by critics, by audiences.

That’s brave enough. But right now, with their profession effectively shut down, they have nothing to cling on to but hope. No wonder that, in October when I poured some cold water on a producer’s attempts to bring back a show at the London Palladium that was done in conditions where I feared the social distancing was — in my opinion — insufficient, one musical director wrote to me in anguish: “Why are you trying to destroy the industry?”

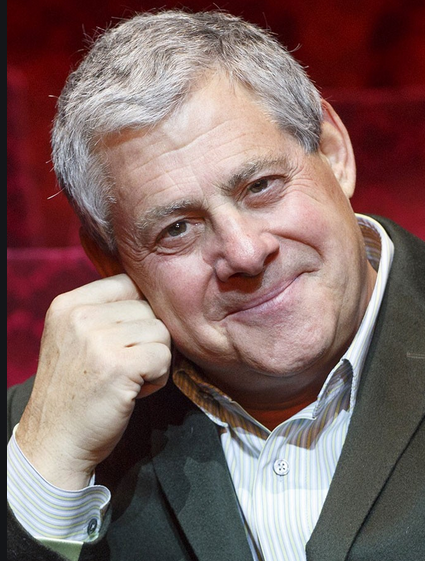

But I do sometimes think it pays to be REALISTIC. Last June, as other theatre owners like Andrew Lloyd Webber were busy planning a Covid-aware trial re-opening of the London Palladium, Cameron Mackintosh (pictured above) announced that the return Les Miserables, Mary Poppins, Hamilton and The Phantom of the Opera would not be until 2021.

The Guardian reported at the time that Mackintosh had said that

….despite the government engaging with “desperate pleas from everyone in the theatre industry”, there had been no “tangible, practical support beyond offers to go into debt”. For the time being, it remains “impossible for us to properly plan for whatever the new future is” he said, which means that the four shows will not return until “as early as practical” next year. “This has forced me to take drastic steps to ensure that I have the resources for my business to survive and enable my shows and theatres to reopen next year when we are permitted to.” Once social distancing restrictions have been lifted, it is anticipated that it will take several months for the productions to be restaged for audiences. In his statement, Mackintosh said he has no investors or venture capital backing and that “everything is funded by me personally”. He recognised that he is “one of the biggest employers in the theatre” and said his companies’ reserves have been severely depleted since lockdown began in mid-March.

Redundancy processes were begun for his production and office staff, with the contracts of cast members terminated. This naturally did not earn Mackintosh many friends, and in the recent Stage 100 list he was completely excluded from a survey that he has previously topped, as I wrote here last week.

But could it be that Mackintosh has, after all, proved to be the most prudent of producers? He did join the attempt to bring back theatre in December by re-opening a concert version of Les Miserables at the Sondheim Theatre, to a significantly reduced capacity; but it, like every other show that came back or newly opened, it was forced to shut again.

Now there’s no sign at all when it, or any of the other shows lining up to open in the coming months as I itemised here last Saturday, will actually be able to.

Meanwhile, in America, Dr Anthony Fauci — the continent’s most famous and authoritative infectious disease expert, at least beyond Trumpland — told a conference held online by the Association of Performing Arts Professionals that the end of the shutdown was in sight. According to a report in the New York Times,

The timeline hinged on the country reaching an effective level of herd immunity, which he defined as vaccinating from 70 percent to 85 percent of the population. “If everything goes right, this is will occur some time in the fall of 2021,” Dr. Fauci said, “so that by the time we get to the early to mid-fall, you can have people feeling safe performing onstage as well as people in the audience.”

He also said that,

if vaccine distribution succeeded, theatres with good ventilation and proper air filters might not need to place many restrictions for performances by the fall — except asking their audience members to wear masks, which he suggested could continue to be a norm for some time. “I think you can then start getting back to almost full capacity of seating,” he said.

That’s the most hopeful sign yet of a possible return to normality. But neither Fauci nor any Broadway producers are yet putting a firm date on it.

I suspect the mistake that British producers have made was to over-anticipate that theatre could return in a changed world; and now that this attempt has failed, they’re actually in a worse position than they would have been had they held off. Not only have they invested money in shows that will not now be returned, but they’ve also undermined at the paying public’s confidence in future bookings. What’s the point of booking for anything right now if, when the day arrives, you’ll only have to plan yet another date?