During the reign of the Nicks (Hytner and Starr, pictured above) at the National Theatre, they initiated many revolutionary acts, including the Travelex £10 season (as it was initially known), which kicked off in 2003 with a season of four productions in the Olivier Theatre where a majority of the seats were sold at just £10, while the remaining third of the best seats were sold at a much reduced top price to the norm, initially just £25. (Travelex would later withdraw their sponsorship, but the annual scheme continued under Rufus Norris’s watch, even if the ticket prices and their distribution in the house also changed, with 50% of the house sold at £15 and staggered higher prices elsewhere, reaching £50 — still some way off the NT’s usual highest price).

It was a scheme that saw the West End replicating some of its headline grabbers, most notably when Michael Grandage launched his own company with a commitment to sell 100,000 seats at £10 for its inaugural West End season (pictured above) in 2012/13, mostly but not all in the balcony of the theatre, with some seats available in other parts of the house for the same low price, which has been continued for all subsequent productions by the company. The Donmar Warehouse found its own sponsor, Barclays, to fund the ‘Barclays Front Row’ scheme, in which 300 tickets across the front rows (of the stalls and circle) being made available for £10 each week.

Most West End shows, in an era of ever-rising price inflation, salved their consciences towards ‘accessibility’ by making at least some tickets at every performance available at £10 or £15, either by lottery or as day seats, either at the theatre or via TodayTix.

I’ve long said that I have no problem with the West End’s highest prices (whether they’re £80 or £150 — a new top price that has just been reached — doesn’t make a lot of difference to those on lower incomes, as they’re unaffordable at either price), as long as they’re mitigated with a sufficient number of realistically affordable seats at the lowest end, and that should go beyond the ten or fifteen tickets made available in the front row as mentioned in the previous paragraph. (My first West End experiences when I first came to London at the age of 16 were from the upper circles and balconies of every West End theatre; when some of those areas now cost up to £40 a ticket, that would no longer be affordable to me).

But an equally big change instigated by the Nicks at the National was the introduction of NT Live, bringing high-definition camera shoots of specific NT productions that were broadcast live, as they were happening, into cinemas up and down the land, and even the world, to New York and beyond — at cinema prices, not theatre ones. This dramatically increased the accessibility and reach of NT productions — especially for sold out productions, where the inevitable cap on available physical seats meant that many thousands more could see a show than would otherwise manage to see it in the theatre.

This has also, valuably, now built up an archive of performance that the NT have recently been able to draw on to establish a new ‘on demand’ paid-for subscription service NT At Home, which means that the shows remain an income stream for the theatre long after they’ve closed.

As the NT’s executive director and joint chief executive Lisa Berger recently remarked,

“At a time when many people were isolated at home, it was uplifting to see audiences recreate the shared experience of visiting the theatre. From homemade tickets to interval drinks, NT at Home was a way of making people feel more connected. And so, since the last stream finished in July, we have been determined to find a way to give our audiences access to these stunning filmed productions online once again. With the agreement from artists, we are now able to showcase an extraordinary range of fantastic NT Live productions and, for the first time, some treasured plays from our NT Archive.”

Again, this was replicated by other companies, from the RSC to the unsubsidised Globe, who set up their own streaming channels. Some West End shows and other companies, including the Donmar, used NT Live platform as well, while other shows (like 42nd Street, An American in Paris and Kinky Boots) were captured for commercial distribution, either on streaming services or even for brief cinematic runs.

The incredible range of performances that have now been filmed in turn had an unexpected purpose during the first lockdown: they became a way for theatrical production to maintain its presence even as every theatre was shut down, and contribute to the entertainment and distraction of the nation. The National screened a different title, for free, every week; while other shows were made available via limited periods of screenings on YouTube channels like The Show Must Go On.

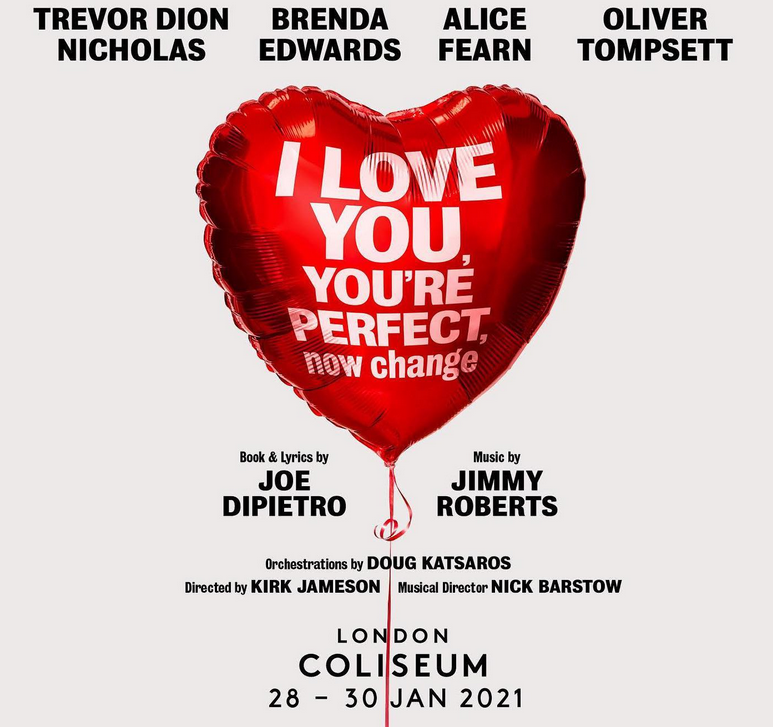

Soon enough, the archive model was replaced by a drive amongst theatre makers, frustrated by not being able to bring their work to a live audience in theatres, creating original content for digital distribution. Initially this had a home made quality — literally so, in the zoom-driven performances from people’s front rooms. But quickly people have stepped up their game, creating professional live streams, like the ones of musicals from Southwark Playhouse (performed not to an audience but in the empty auditorium to camera), or pre-filmed shows like the ones being produced by Lambert Jackson Productions with West End casts performing shows on the London Coliseum stage for streaming (next up, Trevor Dion Nicholas, Brenda Edwards, Alice Fearn and Oliver Tompsett will appear in Joe DiPietro and Jimmy Roberts’s long-running off-Broadway hit I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change from January 28-30, pictured above).

Also being pre-filmed, after its planned premiere run this month was cancelled by the new lockdown, is James Seabright’s production of a new British musical The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, that was already in rehearsal (pictured above). In a press statement issued yesterday, he commented,

“We are sorry not to be able to present this wonderful new show to audiences as planned at Southwark Playhouse, but we are going to film it in the venue next week with broadcast quality cameras and then premiere it online. I commissioned it five years ago, and have loved developing it since then through a series of workshops and a West End concert presentation of an earlier version in 2017, which led to the invitation from Southwark Playhouse to premiere the show at their venue this month. I decided to press ahead with these plans with rehearsals up to Christmas and fit up and get-in since New Year despite the challenges presented by doing so during the COVID-19 pandemic, as I think this magical story of renewal and the importance of family is especially timely. However, the latest national lockdown leaves us with a show ready to perform which we are unable to share with live audiences. I have been inspired by the determination and resolve of our cast, creative team to make this possible whilst maintaining the highest safety standards for everyone on and off stage.”

Last month’s intended live concert performances of Sunset Boulevard in concert at Leicester’s Curve (pictured above) — reuniting cast members of the theatre’s 2017 production — were similarly cancelled by the imposition of Tier 3 restrictions in Leicester, but director Nikolai Foster re-conceived the production as a film/theatre hybrid (currently streaming at specific performance times till Saturday January 9), turning his reconfigured theatre into effectively a large soundstage in which the action took place in different areas of the theatre.

Ria Jones’s Norma Desmond (pictured above) made her first entrance (and later, final exit) from the theatre’s balcony, while Danny Mac — depriving the audience of the original production’s theatre view of him in just his swimming trunks — still flirted shamelessly with the audience direct to camera. Filmed overlaps were super-imposed on the live performance to set locations, much as the original West End production also did. Not all of this worked — and not all of the performances were adjusted to the close-up quality demanded of film, either, but were stage-sized. But it was nevertheless a bold and intriguing way to return the musical to its film origins and co-exist within its heightened framework.

As and when live performances resume again, we can also look forward to simultaneous live broadcasts online of these from places like Crazy Coqs, the London cabaret room that at the best of times can only accommodate less than 100 people, and with social distancing far less than that, but can now reach a global audience online.

But as with so much else we’ve discovered during these long months of lockdown and the changes it has wrought, there’s no going back now. All producers going forward will build digital preservation of their productions into their business models — and a future revenue stream will be available that means that no production need die anymore when the final curtain comes down, either.