Broadway and the West End is strewn with the corpses of bad musicals, some of them (like Rock of Ages or We Will Rock You) which ran for ages. But sometimes, by the same token, good musicals flop and no one quite knows why: the original Blood Brothers, for instance, mustered a West End run of barely six months in 1983; yet when it came back in 1988, it began a run that lasted nearly 25 years. It can sometimes be all a matter of timing, marketing and luck.

Then there are the shows fatally sent down the wrong route by their original productions, as witness most recently Love Never Dies; it wasn’t until new creative eyes looked at it — first when Bill Kenwright re-shaped and significantly re-structured it in the West End (but had to do so on the existing sets), then in an entirely new production in Australia — that it’s true potential was released.

I love to collect seeing them, as it makes me one of a small band of people who’ve seen something. As I once wrote, “Call me morbid, but I love to ambulance-chase dying musicals on their way to the graveyard”.

This musical hall of shame stretches from fiascos like Carrie (adapted from the Stephen King novel about a menstruating teenager into a notorious RSC flop-eretta), Out of the Blue (set in the aftermath of the Nagasaki-H bomb and redubbed ‘A Flash in Japan’ after its short-lived 16-day run) and an infamous musical Oscar about the playwright Oscar Wilde by the one-time radio DJ Mike Read (which opened and closed on the same night in 2004 and it is my eternal regret that I actually missed).

In my latest podcast, which you can hear here, I count down my top ten favourite flop musicals. (On the podcast, they’re revealed in reverse order, but here I post them as a Top 10).

- Carrie The Musical (Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon; and Virginia Theatre, Broadway — now the August Wilson, 1988) Book by Lawrence D Cohen, based on the novel by Stephen King, music by Michael Gore, lyrics by Dean Pitchford

Carrie The Musical — based on Stephen King’s 1974 novel, which was also adapted as a film in 1976 by Brian de Palma with a young Sissy Spacek in the title role, is one of the most notorious flops in musical theatre history, partly for its vast expense (it lost a then-record $8million), short run (five performances on Broadway in 1988), and strong artistic pedigree (it was co-produced by none other than the Royal Shakespeare Company, who staged its world premiere at Stratford-upon-Avon in February 1988 before transferring it to Broadway two months later; its book was by Lawrence D Cohen, who also scripted the 1976 film, and its score was by Michael Gore and Dean Pitchford, best known for their score to another movie musical hit Fame).

A musical that embedded a serious theme about parental religious abuse and school bullying in a show that was was like Glee meets Greek tragedy, its title and status as the King (or maybe that should be Queen) of flop musicals was immortalised in the title of Ken Mandelbaum’s book that chronicled them, Not Since Carrie. As Rocco Landesman, who ran Jujuamcyn Theatres who owned the Virginia Theatre (now the August Wilson) where it ran told Time magazine, “This is the biggest flop in the world history of the theatre, going all the way back to Aristophanes.”

The original Stratford-upon-Avon production, which featured a mixed Anglo-American company, was headed by young British newcomer Linzi Hateley in the title role, and Broadway legend Barbara Cook as Carrie’s mother Margaret White; the show’s Broadway transfer would have marked her first return to the Broadway musical stage since the short-lived The Grass Harp in 1971 (which ran just seven performances). But after the show’s mostly negative critical reaction in Britain, and an incident with the set that could have severely injured her, she pulled out of the transfer, and was replaced by Betty Buckley, who’d had a supporting featured role in the de Palma film.

The original Carrie Linzi Hateley sings the title song in 2020:

In a feature on on the show in the New York Times when it was finally revived off-Broadway in 2012 by MCC at the Lucille Lortel Theatre in Greenwich Village, Patrick Healy wrote about the show’s original production:

“When the lights went black at the end of the first Broadway preview of Carrie, on April 28, 1988, the actress Betty Buckley recalled hearing something she had never experienced in her 20 years in theater: Boos from the audience. Ms. Buckley played the fanatically religious mother Margaret White in the musical, and her character had just been killed by the telekinetic powers of her daughter, the title character. Both Ms. Buckley and Linzi Hateley, who played Carrie, lay on the stage in the dark, hearing the boos; Ms. Buckley recalled that Ms. Hateley, making her Broadway debut, whispered, ‘What do we do?’ ‘We get up,’ Ms. Buckley said in reply. They stood, the lights came on, and the boos turned to cheers and applause for the performers in the show.”

He also went on to describe how “it wasn’t just Broadway audiences who were so shell-shocked that some actually booed the show. Carrie was such a critical and financial flop (at $8 million) that, afterward, its three creators refused to allow another professional production anywhere in the world — a rare act of artistic exile for a title that is a beloved Stephen King novel and a cult classic movie.”

However, they were persuaded to allow MCC to do it; and the company’s then co-artistic director Bernard Telsey said when the production was first announced, “We’re not intimidated by the Broadway blockbuster flop status. By opening Off Broadway, in a smaller and far different production, I think Carrie would receive a fair, fresh look that had nothing to do with its legend.”

I saw both the original Stratford and Broadway productions (I even played a small professional role in memorialising the latter; my first job post-University was editing souvenir brochures of West End and Broadway musicals for Dewynters plc, and we produced one for the Broadway run that have now become collector items!). I also saw the 2012 revival at the Lortel Theatre that starred the late, great Marin Mazzie in the title role; it was actually much improved when done on a far intimate, chamber scale.

When I returned to see it a second time there, I overheard a British-accented man telling his companions how he’d been in the original production. I was intrigued, as I didn’t recognise him; after the show, I approached him to find out what his name was. When I got back to my apartment, I looked up the show online, and he was not credited. So I messaged both Linzi Hateley and Sally Ann Triplett, who was also in the original company, and both confirmed he wasn’t in the show at all! But the show was so notorious he wanted to claim an association!

In 2015, the show finally received its London premiere in a new production at Southwark Playhouse that starred Evelyn Hoskins in the title role and Kim Criswell as her mother.

Trailer:

As I wrote in my review for LondonTheatre.co.uk at the time:

“The show is still not without problems — but it’s also much more than a curiosity to be collected by purveyors of theatrical disasters only (It is, in other words, no Viva Forever! or Stephen Ward).

The chief of those problems is tone: the show wildly oscillates between being a jaunty teenager saga — something between High School Musical, Grease and Glee — and a far more intense dramatic exploration of a deeply troubled and troubling relationship between a controlling, religious single parent and her timid, cowed daughter.

But Gary Lloyd’s new production embraces both extremes with unbounded energy (on the one hand) and searing intimacy (on the other) so that the show lands beautifully in the middle without too many jarring bumps.”

A new podcast series called Out for Blood: The Story of Carrie the Musical, created by two obsessive fans Chris Adams and Holly Morgan, can be heard here, in which they speak to original cast members (and myself!) about the history of the show.

————————————————————-

2. Spider-man: Turn off the Dark (Foxwoods Theatre, Broadway — now the Lyric, 2011), began previews Nov 28, 2010, played 182 previews before opening June 14, 2011 Book: Julie Taymor, Glen Berger and Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa; Music and lyrics: Bono and The Edge

Spider-man: Turn off the Dark set many records: it’s not only a musical that lost more money than any show in history to date (over $70m), but it also played an epic 182 previews that began on November 28, 2010, and continued for some seven months before the show finally officially opened on June 14, 2011. By then, the opening had been postponed three times, and its original director Julie Taymor fired; but though the critics did attend the new opening, most had already lost patience long before that and gone in and reviewed it at the time of its second planned but cancelled opening, by buying their own tickets to do so.

The show, which involved a lot of flying by harness across the stage and even the auditorium, was also famous for the number of injuries that its cast sustained, including most notoriously for Christopher Tierney, a young stunt double for the title character who fell over 20 feet onto the floor of the stage when he leapt off a ramp without his harness being connected to his body.

When I interviewed actor Patrick Page, who’d played the leading role of the villain Green Goblin in that production, he recalled that evening on December 20, 2010 vividly:

“It was in many ways the worst night of my life — I don’t mean to make it about me, as it was obviously much worse for Chris — but in terms of the sheer terror in the moment and not knowing at first whether he had survived. Luckily, he was such a strong athlete that he knew how to take the fall, and managed to roll in the air in just the right way so that he didn’t fall on his head. Though he was severely injured and broke a lot of bones, he made himself better and did physical therapy to a degree that the doctors didn’t expect. We really celebrated when he returned to the show.”

He wasn’t the first, nor the last, actor to be injured: on the very first preview, Natalie Mendoza, who was playing Arachne, suffered concussion when she was hit on her head by equipment in the wings; another stunt-double for Spider-man Kevin Aubin broke both of his wrists, while another actor broke his feet on the same move; while in 2013, actor Daniel Curry suffered a leg trauma after being pinned down by equipment.

ABC Nightline story:

Although the show ended up running for two and a half years, the weekly running costs were so high that it was never able to recoup its investment. Plans for a more streamlined arena touring production were subsequently shelved.

The show’s painful birth and serial betrayals amongst the creative team are chronicled with deep insight and foreboding by book writer Glen Berger in his 2013 book Song of Spiderman — The Inside Story of the Most Controversial Musical in Broadway History.

3. Desperately Seeking Susan (Novello Theatre, London, 2007) Book and concept: Peter Michael Marino. Music and lyrics: Blondie and Deborah Harry.

This jukebox musical — inserting old songs by Blondie and Debbie Harry into the story of the 1985 film of the same name that starred Madonna and Rosanna Arquette — opened in the West End in 2007, where Charles Spencer’s review for the Daily Telegraph was headlined: “Desperately Seeking the Exit.”

Peter Michael Marino (pictured above), an actor and writer who conceived and wrote the book for the musical, turned that headline into the title of a one-man show he created around the fiasco of putting on the show, which he premiered on the Edinburgh Fringe in 2012 and has reprised regularly since, most recently on zoom during the first lockdown last year, which turned out to be a more satisfying theatrical experience than the show itself.

Montage from the original production:

4. Nick & Nora (Marquis, Broadway, 1991) Book: Arthur Laurents. Music: Charles Strouse, lyrics: Richard Maltby Jr

With its solid-gold creative team — lead by West Side Story and Gypsy co-creator Arthur Laurents (who wrote the book and directed), Annie composer Charles Strouse, and Miss Saigon lyricist Richard Maltby Jr — much was expected of Nick & Nora. But after some 71 previews, it only managed a run of 9 performances.

Barry Bostwick, and Joanna Gleason played the title roles, with Christine Baranksi as a supporting character who aspired to be in musicals — and has the show’s funniest song, Everybody Wants to do a Musical:

Listen to audio here:

Seems my testatura’s quite bizarre

My high C may sometimes shriek

Still I hit twice last week

Which proves I can be a musical star

The show played at the Marquis Theatre, a modern theatre that’s located inside the Marriott Marquis Hotel on Broadway between 45th and 46th Street, and has a sad legacy in that five famous Broadway theatres — the Gaiety, Astor, Helen Hayes, Morocco and Bijou — were demolished to make way for the hotel’s construction.

The displaced ghosts of those theatres have not looked kindly on their replacement, which has housed a disproportionate number of flop musicals since it opened in 1986; in addition to Nick & Nora, these include Shogun (1990); Paul Simon’s The Capeman (1998); Andrew Lloyd Webber’s transfer of The Woman in White from the West End (2005); Cry-Baby (2008); Frank Wildhorn’s Wonderland (2011), a short-lived revival of another Wildhorn musical Jekyll and Hyde (2013) and Escape to Margaritaville (2018).

5. Love Never Dies (Adelphi, London, 2010) Book: Ben Elton, Frederick Forsyth, Glenn Slater. Music: Andrew Lloyd Webber. Lyrics: Glenn Slater.

After the smash-hit success of The Phantom of the Opera, Andrew Lloyd Webber had periodically toyed with creating a sequel, and even writing songs for a planned one that, when it didn’t go ahead, he put into his 2000 musical Beautiful Game instead (“Our Kind of Love”). When Love Never Dies finally reached the stage in 2010, he took the melody Our Kind of Love back from Beautiful Game, and with new lyrics by Glenn Slater, repurposed it as the title song there.

After the smash-hit success of The Phantom of the Opera, Andrew Lloyd Webber had periodically toyed with creating a sequel, and even writing songs for a planned one that, when it didn’t go ahead, he put into his 2000 musical Beautiful Game instead (“Our Kind of Love”). When Love Never Dies finally reached the stage in 2010, he took the melody Our Kind of Love back from Beautiful Game, and with new lyrics by Glenn Slater, repurposed it as the title song there.

Soon after previews began at the Adelphi Theatre, a pair of bloggers called the West End Whingers wrote a very negative review of the show which included the infamous phrase re-dubbing the show ‘Paint never dries.’ It’s a label that stuck to the show immediately, and the show never truly recovered from it. In November 2010, some seven months after its original opening in March, the show was briefly closed to allow changes to be put into the show, re-ordered and re-directed by Bill Kenwright, but using the same original sets. In 2011, a brand-new production was staged in Australia by director Simon Phillips that played in both Melbourne and Sydney, and was filmed for video release.

This production was far more successful critically; I attended its opening in Sydney (that starred Ben Lewis as the Phantom and Anna O”Byrne as Christine, both of whom have since relocated to London), and loved it.

Anna O’ Byrne sings Love Never Dies:

A few months later, the filmed version of that production was given an industry screening in London, which I attended. Madeleine Lloyd Webber, wife of the composer, was there and came over to me with her guest, the writer Edna O’Brien, whom she introduced to me with the words: “This is Mark Shenton — sometimes we like him, usually we don’t.”

I have decided I’d like that to be my official epitaph, and included it in a column. A national paper picked it up — and the next time I saw Madeleine at a West End first night, she came up to me and commented that she’d recently read something she’d apparently said to me. I was expecting a denial, but she said: “I don’t remember saying that — but it sounds like something I would say!”

Love Never Dies — and its sumptuous score — will, however, live on, despite its initial failure. That’s by no means certain of his more recent flop show Stephen Ward in 2013, based on the true story of the society osteopath who introduced UK parliament defence secretary of state John Profumo to his mistress Christine Keeler, who was also involved with a Russian spy. The show’s December 19, 2013 opening night was overshadowed by news that arrived just as the curtain came down, that the ceiling of the Apollo Theatre on Shaftesbury Avenue had partially collapsed mid-performance that night, injuring (but fortunately not killing) some audience members. As I reached the street after seeing the messages on my phone, I ran into a leading West End producer who was unconnected to either Stephen Ward or the show playing at the Apollo, and told him what I’d just heard: “An even bigger disaster has happened on Shaftesbury Avenue than happened in this theatre tonight.”

6. Moby Dick (Piccadilly Theatre, London, 1992) Book: Robert Longden. Music and lyrics: Robert Longden, Hereward Kaye

This “whale of a tale”, as the original poster for its first production at Oxford’s Old Fire Station billed it (with a second tag-line, “Stuff Art, Let’s Dance”), starred Tony Monopoly as the headmistress, a drag version long ahead of Matilda’s Miss Trunchbull was also played by a man.

Listen to A Man Happens (audio only):

Producer Cameron Mackintosh subsequently transferred it to the West End’s Piccadilly Theatre, an address that vies with the Shaftesbury for frequently offering a home to flop shows: previous notorious tenants include i (1983, subsequently relaunched as y), Mutiny! (1985), Metropolis (1989), King (a musical based on the life story of Martin Luther King, 1990), Which Witch (1992), and Viva Forever! (a jukebox show based on the back catalogue of the Spice Girls, 2012).

—————————————-

7. Behind the Iron Mask (Duchess Theatre, 2005) Book: Colin Scott, Melinda Walker. Music and lyrics: John Robinson

The composer of Behind the Iron Mask was John Robinson, who managed to get not one but two terrible West End musicals to the West End — four years after this show’s premiere, Too Close to the Sun, based on the life story of Ernest Hemingway, opened — and quickly closed — at the Comedy Theatre (now the Pinter).

In my original review for WhatsOnStage, I wrote,

“Some shows write themselves instantly in the history books, and not always for good reasons. The latest entry into the field of the cataclysmic is Behind the Iron Mask – you might well wish that you were wearing a blindfold if not a full mask (not to mention earplugs) while watching the catastrophe unfold.

At the start, we meet a 17th-century French prisoner (masked throughout, for reasons never explained), who immediately sings “Why am I here?/I can’t move/There’s no escape/I’m here forever.” The dread fear filled my heart that I would soon enough know exactly how he feels. This is a musical about imprisonment that duly (and dully) imprisons its audience for two hours (though at least some had the opportunity to flee in the interval, and many did).

This is one of those phantom exercises in attempting to create a new musical clearly inspired by The Phantom of the opera but it should never have left the drawing board. It exchanges one man in a mask for another, with a parallel story of a gypsy woman drawn unwittingly into his lair and into his heart.

Tony Craven’s grim-looking production – on unbelievably cheap-looking set – fails to harness much energy, though all three actors are to be commended for their apparent sincerity in the face of such adversity. In particular, Robert Fardell’s prisoner – his face hidden by the iron mask that makes him look like a cross between a grey Halloween pumpkin, Shrek and Hannibal Lecter – manages to dredge up some strong vocal tones from the depths of the contraption he’s buried within.”

- 8. In My Life (Music Box Theatre, Broadway, 2005) Book, music and lyrics: Joseph Brooks

This 2005 musical is more famous for what came after it than the show itself, though the show itself was pretty crazy. As Robert Simonson described it in a new story for Playbill, the show is “generally regarded as one of the strangest shows ever to have graced a Broadway stage. A love story between a young woman journalist who has obsessive-compulsive disorder and singer-songwriter with Tourette syndrome, its characters also included a slovenly, jingle-loving God who wears a baseball hat, and a transvestite angel who has a dance number with a skeleton. The finale featured a giant lemon.”

Medley of songs performed at 54 Below by Courtney Balan, Laura Jordan, Kilty Reidy:

However, more sadly, Joseph Brooks, who wrote book, music, lyrics and directed it (and was best known for the Oscar winning song You Light Up My life in 1977, a No 1 hit for Debbie Boon). committed suicide in 2011, after his life rapidly unravelled. In 2009, he was arrested on charges of raping 11 young actresses after luring them to his apartment with the promise of movie roles. In 2010, his son, Nicholas Brooks, 25, was charged with strangling his girlfriend.

Though the original cast was not exactly star-studded, the show’s swing was Jonathan Groff, who would go on to musical theatre fame as a two-time Tony nominee for Spring Awakening in 2007 and Hamilton (in 2016).

9. Legs Diamond (Mark Hellinger Theatre, Broadway, 1989) Book: Harvey Fierstein, Charles Suppon. Music and lyrics: Peter Allen.

This 1989 musical, with songs by Peter Allen who also starred in the title role, was another show to play more previews (72) than actual performances (64) before it closed. It was also, sadly, the last musical to ever play at the beautiful Mark Hellinger Theatre; given the depleted state of Broadway at the time, the Nederlanders (who also produced the show) sold the theatre to the Times Square Church after the failure of Legs Diamond, who have occupied it ever since.

Peter Allen would himself die just over three years later, of an HIV/AIDS related condition. His life story — and back catalogue — would, however, become the basis of a far more successful musical The Boy From Oz that was seen on Broadway in 2003, when Hugh Jackman played him.

10. The Fields of Ambrosia (Aldwych Theatre, London, 1996) Book, lyrics: Joel Higgins. Music: Martin Silvestri

This musical, based on the 1970 film The Travelling Executioner, had a book and lyrics by Joel Higgins, who also played the lead role of the executioner Jonas Candide, who travels around the US with his electric chair dispensing “justice” along the way. Its score was written by Martin Silvestri, whose own wife Christine Andreas played the executioner’s next victim, but whom he seeks to save from the chair after he becomes smitten by her.

No one who saw it will ever forget The Fields of Ambrosia or its title number, with the rhyme, “Where everyone knows ya.” But my favourite moment, quite possibly of any flop musical ever, was the song sung by the travelling executioner’s assistant after he’s been gang-raped in prison: “If it ain’t one thing, it’s another.”

Title song:

No wonder that Paul Taylor, reviewing its short run in The Independent in 1996, dubbed it “a reprehensibly enjoyable new musical”. He also wrote, “The second half of the show left this critic weak with bliss as it trampled over good taste and political correctness like a herd of bullocks.”

But what’s especially amazing about The Fields of Ambrosia isn’t just that it found a home at London’s Aldwych Theatre, but that it had a prior production three years before, at the George Street Playhouse in New Jersey in 1993, so it can’t have been a shock to anyone just how bad it was!

WHAT’S MISSING…..

There are too many other musical theatre flops to even begin to list them.

But there are a fair few I’d love to see again somehow, and maybe find the success that eluded them first time around. In recent years, I’ve loved shows like Bend It Like Beckham, The Girls (based on Calendar Girls) and Made in Dagenham, each of which failed to ignite at their box offices, but which deserve another outing.

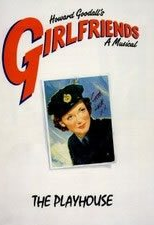

The first of those, of course, had music by Howard Goodall (who also wrote the jingle music for this podcast); and its his second West End score, for Girlfriends (that ran briefly at the Playhouse in 1987) that I’d most love to see a return of. It has a simply gorgeous score, and each time I’ve seen it — and I’ve tracked it down to a student production at Mountview, and fringe productions at Walthamstow’s Ye Olde Rose and Crown and Southwark’s Union Theatre — I’ve loved it more. A 2018 concert staging by the London Music Theatre Orchestra, featuring a cast that included Lucie Jones, Lauren Samuels and Rob Houchen, amongst others, was happily recorded.

NEXT FRIDAY:

My ShenTens podcast and feature here will count down my top ten favourite West End theatres.

AND FINALLY:

Special thanks to my producer Paul Branch; Howard Goodall, for theme music; and Thomas Mann for the logo design