In a month and four days time — March 16 — we will reach the first anniversary of the sudden shut down of every West End theatre, followed the same or next night, by every other theatre in London and around the country, thanks to Boris Johnson’s announcement on what would become the first of his daily press conferences on that Monday afternoon:

“Now is the time for everyone to stop non-essential contact with others and to stop all unnecessary travel. We need people to start working from home where they possibly can. And you should avoid pubs, clubs, theatres and other such social venues.”

In a move that would come to typify Johnson’s behind-the-curve approach to the advancing threat of the virus at every turn, he did not spell out that such venues HAD to shut by legal mandate; merely that the public should avoid them.

SOLT took the responsible decision to tell their members to shut with immediate effect. (I was en route to try see City of Angels at the Garrick that night, ahead of an opening night planned for later that week, that I feared the show would not make; and I was right. When I arrived at the theatre, I found that even that night’s performance was cancelled. The show would never re-open).

On that day, too, the death toll from Covid had risen from 35 to 55. As The Guardian reported then, “The prime minister said the disease was now ‘approaching the fast growth part of the upward curve’, with London in the vanguard.”

And here we are, nearly exactly a year later, with over 100,000 deaths and counting. What followed was what Dominic Cavendish yesterday called in the Telegraph “the theatre sector’s longest period of closure since the Cromwell era and the subsequent outbreaks of plague”. And apart from a brief return for a handful of West End and other theatres in November — all under strict rules for social distancing being enforced — they’ve all gone back into hibernation, and there’s no return date now for if or when they’re likely to re-open, or under what conditions.

So my ShenTens today is particularly bittersweet, as we can’t actually go to any at the moment: my favourite West End theatres. (In future editions, I will look at both my favourite regional theatres around the UK, as well as the extensive network of theatres in London beyond the West End).

“The West End” is strictly speaking a geographical term, first used in the early 19th century to describe areas to the west of Charing Cross, but in theatrical terms, not every theatre thus defined is necessarily located there. While it is true that most are located in a relatively narrow geographical area that stretches from the Embankment north to Oxford Street, and from Regent’s Street east to Holborn, a West End theatre is one that has full membership of the Society of London Theatre, the trade body that represents theatre owners and producers, so it also includes places like the National, Old Vic, Barbican and Open Air Theatre, Regent’s Park, which are all well outside of that geographical reach.

Here are my Top 10 Favourite “West End” theatres according to this expanded definition.

1.National Theatre

The National Theatre, of course, is more than a theatre; it is a statement — that theatre is a central part of our national life, and exists as a physical entity as much as an idea. (Outside of England, the National Theatre of Scotland and National Theatre Wales — founded in 2006 and 2009 respectively — have taken the opposite approach, existing without their own physical homes but using different theatres and site specific locations as they need them).

Founded in 1963 by Laurence Olivier — a barn-storming actor-manager of the old school who had also become an international movie star — it originally set up shop with a lease on the Old Vic (pictured above, on the occasion of the theatre’s 200th anniversary in 2018), before commissioning its own purpose-built theatre, designed by Sir Denys Lasdun, on a site beside the river on the nearby South Bank, which opened — in stages — from 1976 onwards. Olivier passed the baton of artistic directorship to Peter Hall in 1973, who was succeeded by Richard Eyre in 1988, then Trevor Nunn in 1997, and Nick Hytner in 2002, before Rufus Norris took over in 2015.

It comprises three very different auditoria — the 1,100 Olivier amphitheatre (modelled on the ancient Greek theatre at Epidaurus); the more conventional proscenium arched Lyttelton (seating 890 people on two levels); and the flexible spaced Dorfman (originally called the Cottesloe, and renamed in 2014 in recognition of the donor who made its refurbishment possible as part of a wider project to revamp the NT building, seating up to 400, depending on its configuration).

It has also, over the years, developed a number of other temporary spaces, including a season in a reconfigured Lyttelton (during Trevor Nunn’s tenure in charge) that created an auditorium that was all on one continuous level in the main house and had a separate smaller studio space in the upstairs bar area; while The Shed was created as a temporary studio during the closure of the Cottesloe, which operated from 2013-2016. The NT Studio (founded under the directorship of Peter Gill in 1985) is the theatre’s private development space, and is housed in a building across the street from the Old Vic in the Cut, currently run by Emily McLaughlin as head of new work.

The National has become arguably the most important and influential theatre building in London, and possibly the UK, seeding any number of prominent acting, directing and writing careers, as well as productions that have begun life their life here before fanning out into the West End, Broadway and indeed the world. These international successes have stretched from the original productions of Amadeus in 1979 and Alan Bennetts smash-hit plays The Madness of King George III (1991) and The History Boys (2004) to Stephen Daldry’s revival of JB Priestley’s An Inspector Calls (1992) and the hit adaptation of an old Goldoni comedy as One Man Two Guvnors (2011).

Musicals have also become a regular feature, with hit productions of Guys and Dolls (1982, revived 1996) and the dazzling original musicals Jerry Springer — the Opera (2003, pictured above is Alison Jiear and company) and London Road (2011), which are amongst my favourite musicals of the century so far.

The NT has also become staged some brilliant productions of Sondheim (including the UK premiere of Sunday in the Park with George in 1990, and revivals of Sweeney Todd in 1993, A Little Night Music in 1995 and Follies in 2017) and Rodgers and Hammerstein (Carousel in 1993 and Oklahoma! in 1998, both of which went onto Broadway transfers, and South Pacific in 2001).

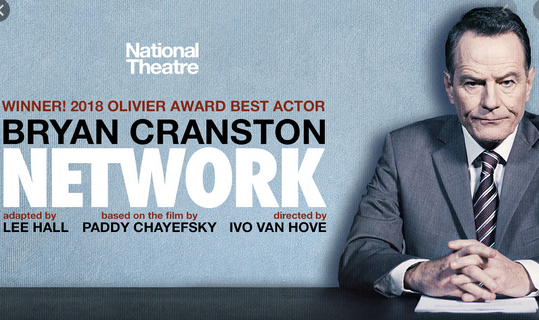

More recent hits, all of which have transferred to Broadway or were about to (when the pandemic struck), have been Network (2017), Hadestown (2018) and The Lehman Trilogy (also premiered at the NT in 2018).

There is no theatre I visit with more confidence and expectation of having a good night than the NT, or more of a sense of easy welcome. It’s the least stuffy theatre building in London, with its foyers that open out onto beautiful river views open to visitors all day, who are welcome to come in and simply have a coffee or a drink, or visit the well-stocked ground floor theatre bookshop that is open all day, or visit one of the foyer exhibitions. The neglected subterranean car park could do with a spruce-up, but other than that, this is my favourite theatre building in London to visit.

2. London Coliseum

There is no more beautiful — or grander — theatre auditorium in London to my eyes (and especially ears, as that’s one of the reasons we go there) than the London Coliseum. Though the Royal Opera House may be more ‘epic’ in scale, it also feels remote and stuffy to me; I once had a conversation with a former head of press there in which I said that, although I’m a relatively sophisticated theatregoer, I didn’t feel welcome at the Opera House, to which he replied, “I can’t deal with your psychological problems.”

In other words, the feeling that it was inaccessible was mine, not theirs; and yet on one of the (very) rare occasions I’ve been there, to attend the Olivier Awards that were held there, I was seated next to Reece Shearsmith, and as he looked around the auditorium with awe and wonder, he said to me he’d never been here before.

Now Reece is a major cultural figure, part of the League of Gentlemen comedy team; and he, too, found it not part of his life until he was invited as part of a theatre awards ceremony. The Opera House simply fails to reach the lives of most ordinary — and some extraordinary — Britons.

By contrast, the London Coliseum — home to English National Opera since 1968, when it was called the Sadler’s Wells Opera Company (it changed its name to ENO in 1974) — always feels a far more democratic space. That’s partly because the seats are a lot cheaper than at the Opera House, and as the name implies, its productions are sung in English. Though the cheapest seats in the top balcony (pictured above), may be quite far away, in common with other theatres designed by the great Victorian theatre architect Frank Matcham they offer perfect views of the stage without giving you vertigo, as the awful amphitheatre at the Opera House guarantees.

The theatre also has past form as a home of more populist entertainment: indeed, it originally opened in 1904 as the London Coliseum Theatre of Varieties. In the 1940s and 50s, it operated as a regular West End theatre that hosted a series of transfers of big Broadway musicals, including Annie Get Your Gun (1947), Kiss Me, Kate (1951), The Pajama Game (1955), Damn Yankees and Bells Are Ringing (both 1957).

ENO have re-introduced musical theatre to the house, leasing it during certain periods of the year when opera is not being presented here to other impresarios, that in recent years have seen productions of Sweeney Todd (with Bryn Terfel and Emma Thompson), Chess, the Broadway production of the Gloria Estefan jukebox musical On Your Feet and the French Canadian blockbuster Notre-Dame de Paris staged here; there was also an admittedly awful production of The Man of La Mancha. A revival of Hairspray, with Michael Ball due to reprise his Olivier award performance as Edna Turnblad, was due to run here last year; it was postponed to this year because of the pandemic, but looks like it will postponed again

3. Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

London’s most venerable and prestigious musical theatre house, the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane — whose current building dates from 1812 — stands on the oldest theatre site still in use in London, where three previous buildings have stood.

The first theatre on this site didn’t last long: it opened in 1663, but was closed by the great plague of London by order of the Crown in 1665 — an unfortunate echo of the circumstances we’re currently in. It reopened 18 months later, but then a fire burnt it to the ground in 1672. The second theatre lasted a lot longer — it opened in 1674, and was demolished in 1791. The third theatre, which opened in 1794, was again short-lived — it burnt down in 1809, with its then-owner Richard Sheridan reported to have watched the flames from the street while drinking a glass of wine, and apparently he said: “Surely a man may be allowed to take a glass of wine by his own fireside”.

The fourth and current building opens in 1812, with the portico that stands at the front entrance added in 1820, and the colonnade that runs down the side of the theatre to the stage door in Russell Street being added in 1831.

The theatre has among the most beautiful and ornate public areas of any theatre in London that makes it look a bit like a Royal Palace — an impression amplified by the statues and sweeping staircases (pictured above left) that lead up to its royal circle and a Grand Salon bar (pictured above right) there that is probably the largest and grandest public space of any West End theatre.

The auditorium itself is more conventional, with the audience seated on four levels, though I’m looking forward to seeing at again after its current massive refurbishment project undertaken by current owner Andrew Lloyd Webber; it was due to open last summer to house the UK premiere of Disney’s Frozen; this was of course put on hold by the pandemic, and there is no date yet for when this will finally happen.

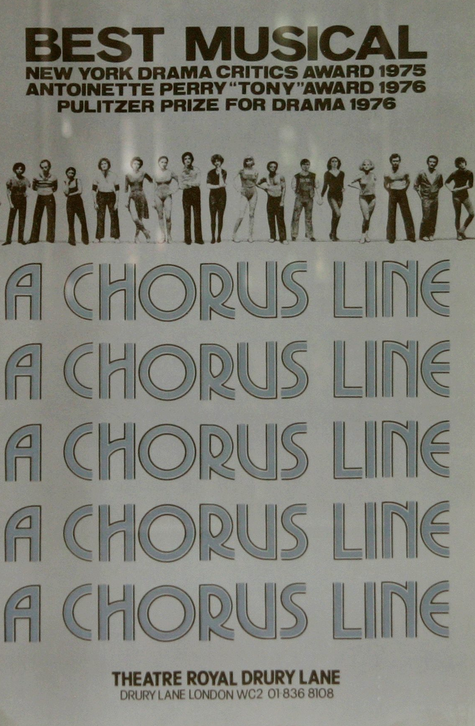

Drury Lane has long been the premiere West End home for musical imports from Broadway as well as British originated productions. My first visit there was in fact my very first trip to a London theatre when I arrived here, aged 16, from South Africa where I grew up. I still remember the exact day and date: Saturday March 31, 1979. I had grown up listening to the Broadway cast recording of A Chorus Line — and fallen in love with it.

March 31 was also the last day of the run of its West End transfer. I went to the box office and bought myself a ticket in the top balcony for 50p. And because the house wasn’t full, I was moved down to the rear stalls instead. That production remains an indelible experience. In the 1980s, it was here that I first saw the short-lived Broadway imports of Sweeney Todd (it ran for just three and a half months in 1980), Tommy Tune’s production of The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1981) and Bob Fosse’s Dancin’ (1983), before Dayid Merrick’s smash-hit 42nd Street transferred here in 1984, and ran for five years to 1989 (a revival in 2017 was the last production to play here before the theatre shut for refurbishment in 2019).

It was followed by the original production of Miss Saigon in 1989, that achieved the longest-run of any musical to date here, running to October 1999. Cameron Mackintosh, who had begun his career in the theatre sweeping the floor here as a stagehand and also produced Miss Saigon, then premiered another new musical, based on John Updike’s The Witches of Eastwick in 2000.

Transfers of the National Theatre productions of My Fair Lady and Anything Goes followed 2001 and 2002 respectively (the original Broadway production of the former had also played here for five and a half years form 1958, with its original Broadway stars Rex Harrison, Julie Andrews and Stanley Holloway reprising their performances), before The Producers transferred from Broadway in 2004. Subsequent tenants have included a revival of Oliver! (2009), the transfer of Shrek from Broadway (2012) and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory in 2013, which ran to 2017

4. Palace

The Palace Theatre, standing on an imposing corner site on the corner of Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road, probably has the most spectacular front-of-house facade of any West End theatre. In 2016, it became the perfect original home of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. It was once said that producers need to cast their theatres and well as their shows; this was the perfect example of that, since the theatre is the most Hogwartian in London.

Harry Potter is, though, unusually a play to run at this address; it is more usually used to house musicals. Originally commissioned by theatre impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte, who also built the Savoy Theatre as a home for his D’Oyly Carte Opera Company (see 9 below), it was originally named the Royal English Opera House when it first opened in 1891; but it was quickly renamed the Palace Theatre of Varieties, and featured a different bill of fare.

It proceeded to become a popular musical theatre house, with the original Broadway productions of The Sound of Music and Cabaret (starring Judi Dench as Sally Bowles) transferring here in 1961and 1968 respectively. It then became the original West End home of Jesus Christ Superstar in 1972, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s musical that had premiered on Broadway the year before; it would, during a run that lasted till 1980, become the longest running musical in West End history up until then. Lloyd Webber would subsequently smash his own record with Cats, though that was in turn eclipsed by Les Miserables that transferred to the Palace from the Barbican in 1986, and ran here for 19 years, until moving to the smaller Queen’s (now the Sondheim) in 2004, where it remains to this day.

Lloyd Webber also premiered his song cycle Song & Dance at the Palace in 1982, and The Woman in White in 2004. Other Broadway imports here have included On Your Toes (in 1984) and Spamalot (in 2006); while a stage version of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert transferred here from Australia in 2009. Prior to Harry Potter’s arrival, the theatre hosted runs of Singin’ in the Rain (transferred from Chichester in 2012) and a new stage musical film version of the film The Commitments in 2016.

The Palace became the first theatre that Andrew Lloyd Webber would acquire ownership of, when he bought it in 1983 and located his production offices above the theatre (where, famously, Prince Edward was once an employee); he sold it on to Nimax Theatres in 2012.

5. Victoria Palace

Another Frank Matcham designed glory, this spectacular musical theatre house is a little beyond the usual geographical spread of the West End itself, though its location opposite a busy London railway station makes it ideal for people coming in from the towns and cities served by it that include Brighton and Chichester. It opened in 1911, a year after Matcham had opened the London Palladium (another beautiful theatre that doesn’t quite make it onto my Top Ten list, mainly because it is no longer programmed for open-ended runs).

Cameron Mackintosh acquired the theatre in 2014, and when its then-tenant Billy Elliot (which ran there for some 11 years) closed in 2016, he embarked on his most extensive, and expensive, refurbishment project of any of his theatres yet, turning it into one of London’s most sumptuous and beautiful theatres, before re-opening it in December 2017 with the transfer of the Broadway smash-hit Hamilton.

The longest-running show to date here was Buddy, a jukebox celebration of the career of pop star Buddy Holly, that ran for 13 years from 1989 (before transferring first to the Strand — now the Novello — and then the Duchess). That show’s advertising tag-line — “It’s Buddy Brilliant!”, taken from The Sun’s review of the show — remains one of my favourite-ever.

6. Wyndham’s

The perfect, chocolate-box jewel of Wyndham’s Theatre originally opened in 1899, designed by WGR Sprague, one of the most prolific of all West End theatre architects. Now owned and operated by Cameron Mackintosh’s Delfont Mackintosh Theatres, Sprague also designed the Coward (formerly the Albery), Novello (formerly the Strand), Gielgud (formerly Globe) and Sondheim (formerly the Queen’s), all also owned by DMT. Mackintosh has overseen loving refurbishments of each of them, and was due to add yet another Sprague theatre, the Ambassadors, to his portfolio, before its then-owner pulled out of negotiations and sold it instead to Ambasadors Theatre Group.

Because of its intimate size, Wyndham’s typically hosts plays more than musicals, though the Menier Chocolate Factory revival of Sunday in the Park with George transferred here in 2006, and Audra McDonald made her London theatrical debut in Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar and Grill here in 2017.

Star players are often attracted to this prestigious house, including Madonna (who made her West End debut in Up for Grabs here in 2002), Kenneth Branagh, Derek Jacobi, Judi Dench and Jude Law (who all starred here in a Donmar Warehouse produced season of four plays, all directed by Michael Grandage), and Sirs Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart in Pinter’s No Man’s Land in 2016.

The latter produced my most hilarious interview encounter yet, when I went to meet McKellen at the theatre. He insisted on conducting the interview sitting in the alley that runs behind it, so he could smoke; this meant, of course, frequent interruptions from passing pedestrians, who wanted to engage with him (not to mention a paparazzi photographer who started taking pictures, much to his irritation). Finally, a young woman stopped in front of me: “Are you Mark Shenton?”, she asked. “I’m such a fan!” Then she spotted Sir Ian. He was already smirking at this point — slightly affronted, I felt, that it was me, not him, who was recognised first. I assured him that I’d not set it up! I then asked her to take a picture of us, which she duly obliged (see above!), before taking one for herself

7. Prince of Wales

This gorgeous art deco theatre was the second theatre acquired by Cameron Mackintosh after the Prince Edward, and he oversaw another spectacular refurbishment of it in 2004, which includes a wonderful stalls bar — the Delfont Room — that is probably second only to the Grand Salon at Drury Lane in terms of scale and beauty in London.

On a personal note, I oversaw and hosted the annual Critics’ Circle Theatre Awards in this room during the nine years I was chair of the drama section (pictured above, Judi Dench after she received the 2016 Trewin Aawrwd for Best Shakespearean Performance for her role in The Winter’s Tale at the Garrick).

The theatre, which originally opened on this site in 1884 but was entirely rebuilt in 1937, has been a regular home for the import of Broadway musicals, including the original London runs of Funny Girl (in 1966, with Barbra Streisand reprising her Broadway performance as Fanny Brice), Sweet Charity (1967) and Promises, Promises (1969). The Book of Mormon has been playing here since 2013.

It is the most Broadway-like of any West End theatre, which are mostly on two levels, comprising only a stalls and circle level.

8. Barbican Theatre

Originally built — to the Royal Shakespeare Company’s direct specifications — as part of the Barbican Centre which opened in 1982, the company relocated here as its London home, from the West End’s Aldwych Theatre that it had previously rented, and the Donmar Warehouse that was created as a studio space for the company in the 1970s. (The studio work was moved to the subterranean Pit Theatre in the bowels of the Barbican).

The RSC programmed the theatres here for 20 years, both transferring shows from Stratford-upon-Avon as well as originating new shows here, including most famously, the 1985 premiere of Les Miserables that subsequently transferred, under co-producer Cameron Mackintosh’s auspices, to the West End in 1986 and subsequent world domination.

But then in a fit of ill-considered hubris, then artistic director Adrian Noble announced in 2002 that the RSC would be leaving the Barbican, and arranging West End residencies for itself. The company found itself intentionally homeless for the next decade, flitting from West End house to West End house, until in 2013 Gregory Doran renewed the company’s association with the Barbican, where it is now a visiting company alongside there theatre work programmed by the venue itself, so it only has part-time access to it.

Not everyone likes the Barbican, not least of all me; its public spaces feel like a massive, characterless airport terminal, and it has often felt just as terminally ill-run as Heathrow airport. I once complained about the box office so fiercely when it was mismanaging the ticketing of an external event that wasn’t taking place at the venue itself; when I arrived at this other venue, the clerk at the pick-up desk was waiting for me. He handed over my tickets, which came with an additional computer-printed stub at the front that had my name and HANDLE WITH CARE!!!! printed on it. The box office had just proved their utter incompetence by printing out private information it stored about their customers for them to see.

On another, even more infamous occasion, I attended a theatre event at the Barbican, Theatre, not of the RSC’s making, in which a six-hour Philip Glass opera Einstein on the Beach was being presented there in 2012. Throughout the opening hour, someone was taking photographs of the show with a flash camera; as the show had no interval, but was performed continuously across its six hours, there was no opportunity to intervene. But the flashes did stop after a while, until resuming again in the final hour.

I worked out exactly where they were coming from, and where the offender was sitting; at end of the performance, I tried to report it to a front-of-house staff member, but none was to be found, so I went in search of the offender myself. As she was in the middle of a row, she had not left yet; so I approached her, and admonished her for her breach of etiquette so forcefully that the hum of the auditorium suddenly quietened.

After I was finished, another member of the audience who’d been sitting near her approached me: he said he’d tried to tell her to stop, but she’d refused. He then said, “Do you realise who she is?” I didn’t. He revealed it was Bianca Jagger!

I subsequently wrote a column about the incident for The Stage, that was in turn picked up by several national newspapers (see above). The Guardian even ran a feature about whether she was in the wrong to have acted as she did, and it set out some guidelines for audience members to follow. It concluded with this one:

“When something is being a distraction nearby, you have a duty to do something. Others further off may be equally annoyed, but powerless, so they are depending on you. Remember that – and don’t rely on having an enraged Mark Shenton at the end of every row.”

So I have a long and tangled history with the Barbican myself that has sometimes not been the happiest. But I still think that its theatre is one of the finest in London, and its long rows of seating amongst the most comfortable of any theatre, too. It also has two utterly spectacular features: the beautiful way the side entrance doors to each row silently shut simultaneously as the show begins; and the way the most spectacular fire curtain in London seamlessly closes, too.

9. Savoy Theatre

The first of two theatres commissioned by impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte (see 4 above for the other), the Savoy opened in 1881, as a home for his D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, who were most famous for premiering the light operettas of Gilbert and Sullivan. The duo’s final eight operettas were all premiered here, including such classics as Iolanthe, Princess Ida, The Mikado, Ruddigore, The Yeomen of the Guard and The Gondoliers.

The theatre was the first public theatre to be lit entirely by electricity — a fact that didn’t play a part in either of the fires that the theatre suffered in 1933 and again in 1990 (the latter just as a production of Ben Travers’s Thark! was about to transfer from the Lyric Hammersmith, but would therefore never do so). A previous transfer from the Lyric Hammersmith of the original production of Michael Frayn’s Noises Off was a long-running success here in 1984/5.

Following a gorgeous refurbishment of the theatre, it reopened in 1993, though the finish in silver painted surfaces sometimes makes the auditorium unusually bright as the stage lighting reflects off it.

A delightful transfer of one of Broadway’s most perfect-ever musicals She Loves Me followed in 1994 (a show that featured in my opening podcast of favourite-ever musicals); another entry in 2011, Murderous Instincts, narrowly avoided inclusion in my top of the flops podcast last week. That show went through more directors, according to Paul Taylor in The Independent, than Elizabeth Taylor has had husbands, with one — Michael Rooney, son of Mickey (whom had himself appeared at the theatre in Sugar Babies in 1988), giving what the same critic called “a delicious new twist to the old gag about directors ‘phoning in a production’ when, with his application for an emergency work permit blocked, he actually tried to oversee the show from Paris.”

Another tenant, Judy Garland’s younger daughter Lorna Luft presenting her solo autobiographical show Songs My Mother Taught Me in 20004, produced one of my favourite stingers I’ve ever read in a review, with Time Out referring to her wearing a shoulderless dress, “presumably to reveal the absence of a chip.”

Highlights from the last decade and a half here have included a beautiful production of Porgy and Bess (2006, directed by Trevor Nunn), the transfer from Broadway of Legally Blonde (2010, with Sheridan Smith, who also transferred here in the Menier Chocolate Factory production of Funny Girl in 2016), Gypsy (2015, starring Imelda Staunton as Momma Rose, transferred from Chichester Festival Theatre) and the West End premiere of the 1981 Broadway musical Dreamgirls (2016).

10. Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre

As uncertain as we are if and when theatre will return, Regent’s Park blazed a trail last year by being the first theatre that’s a member of SOLT to re-open last summer, when it revived its 2016 production of Jesus Christ Superstar, though last year it was presented to reduced capacity, socially-distanced audiences (not the full house shown in the picture). This wonderful production, directed by artistic director Timothy Sheader (who presented his first season here in 2008) and choreographed by Drew McOnie, won the 2016 Olivier for Best Musical Revival; it subsequently had a summer run at the Barbican in 2019, while another Tim Rice/Lloyd Webber musical Evita was staged here in 2019 (and was due to run at the Barbican last summer as well0.

Other recent shows have moved to New York (the 2010 revival of Into the Woods was subsequently re-staged at Central Park’s outdoor Delacorte Theatre in 2012) and the West End (Crazy for You, in 2011).

As much as I invariably fret about what the weather will bring ahead of a visit to this theatre, which is of course open to the elements, it’s a special pleasure on a balmy night. On one press night, however, for a revival of Babes in Arms that was directed by Judi Dench, the rain started falling; my waspish companion turned to me and said, “It’s God crying at the sound of the singing!”

This year the theatre’s planned premiere of a new musical version of 101 Dalmatians, originally scheduled for last year, has again been postponed already; but I’m hoping that its planned revival of Carousel — likewise deferred from last year — will still go ahead.

WHAT’S MISSING…..

There are countless other London theatres I also love (and one or two I passionately dislike — like The Other Palace and the Trafalgar Studios, at least as the latter was previously reconfigured but is now returning to its original two-level layout when it re-opens as the Trafalgar, so I hope to be able to enjoy visiting it again). But there’s no room for them all here!

In terms of beauty, I also adore the stunning Theatre Royal, Haymarket; the Apollo (with its gorgeously ornate auditorium); the Garrick, the Playhouse and the intimate Criterion. The Shaftesbury also has a faded grandeur; although its independent owners have refurbished the backstage and stage areas, the auditorium still awaits a spruce-up. Cameron Mackintosh’s refurbishments of the Novello, Gielgud and Sondheim (previously respectively the Strand, Globe and Queen’s) have also been spectacular.

Ditto the wonderful Royal Court, the only producing theatre apart from the National, Open Air Theatre and intimate Donmar Warehouse that are full members of SOLT.

The Adelphi, Piccadilly, Lyric on Shaftesbury Avenue and Duke of York’s on St Martin’s Lane are all functional than particularly distinguished. But the St Martin’s is a rare, wooden-panelled gem — if only we got to visit it more often, but alas we don’t, as it has been home to The Mousetrap continuously since 1974.

NEXT FRIDAY: My ShenTens podcast and feature here will count down my top ten favourite Broadway leading ladies.

AND FINALLY:

Special thanks to my producer Paul Branch; Howard Goodall, for theme music; and Thomas Mann for the logo design