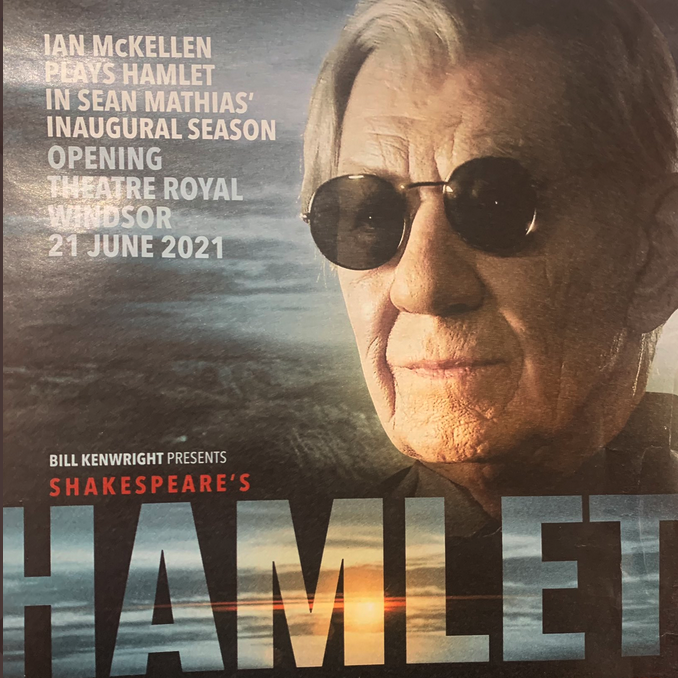

Ian McKellen has never been an actor to shirk a challenge — or do things by halves.

Having first played the title role of Hamlet fully 50 years ago, aged 31 — the age that Hamlet is at the end of the play — he has now returned to it, aged 82. In-between, he has played pretty much all the great Shakespearean roles — Macbeth (RSC 1976, with Judi Dench), Romeo (RSC 1976, with Francesca Annis as Juliet, now playing the tiny role of the Ghost here), Leontes (RSC 1976), Sir Toby Belch (RSC 1978), Coriolanus (National 1984), Iago (RSC 1989), Richard III (NT 1990 and world tour), Prospero (West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds, 1999) and of course King Lear (RSC 2007, and Chichester/West End 2017/18).

“Our little life is rounded with a sleep,” says Prospero in The Tempest; but having twice played King Lear, the ultimate older actor’s Shakespearean role, he is rounding his rather bigger career with another Hamlet.

On his personal website, he describes his and his original director Robert Chetwyn’s approach to the play the first time he did in 1971:

“Bob and I talked before rehearsals and he persuaded me that we shouldn’t tell the Olivier story of ‘a man who couldn’t make up his mind.’ Our Hamlet was a youngster who knows exactly what has to be done, but lacks the manly resources to do it. He grows up until finally he is ready: and the readiness is all. Many of Shakespeare’s heroes go on such painful journeys to maturity.”

To now watch a long mature actor, with a lifetime’s experience behind him, playing the role adds unexpected layers — and of course, an expected dose of melancholy, too, as it is intensely moving to watch a play about a young man facing up to the existential terrors of death and embracing it, willingly, to escape his depression, played by an actor on his final lap. (And in a lovely bit of poetic casting, McKellen will next play Firs in a new production of The Cherry Orchard with most of the same company at this theatre, a small but significant role of an old man who is left to die in the abandoned house at the end of the play).

McKellen, even at 82, still has an agile gait — at one point he’s in an athletic vest pedalling on an exercise bike, at another descends a vertical ladder; and it culminates in a no-holds-barred sword fight); but more importantly, it is that sonorous, distinctive voice that brings so much melody as well as meaning to every line. He has lived these lines, and it shows.

Working with his former partner and frequent directorial collaborator Sean Mathias, he scales new heights in an already astonishing dramatic repertoire; moment to moment, you do not even think about his real age.

And that’s where this production has made both a radical and revealing intervention: it also throws all the other roles up for grabs, too, in an approach that is entirely colour, gender and age blind, and sees Polonius, for example, played by a woman (Frances Barber, a late replacement for Steven Berkoff who withdrew during rehearsals).

As Jenny Seagrove — who is playing the principal role of Gertrude, Hamlet’s mother, though she is in fact 18 years McKellen’s junior — has warned in an interview: “It’s a very avant-garde production. It’ll be Marmite. People will either love or hate it. But we want them to look beyond the exteriors and see the stories of the characters.”

But the superb Seagrove, too, proves the utter fearlessness of the method in the apparent madness. Adopting a Germanic accent that reminds us of the ancestry of those in the nearby House of Windsor whose castle walls are just yards from the theatre, she’s instantly compelling; you hang on her every word.

In fact at a time when one child of that dysfunctional real-life Royal Family is making headlines daily — just yesterday we had Prince Harry’s announcement of a no-holds-barred autobiography — this play comes piercingly to life as a study in royal dysfunction.

Designer Lee Newby’s industrial set of a cross-bridge that dominates the stage above a steep bank of stairs to reach it, with an onstage audience occupying benches below it, allows the play to unfold with a startling immediacy; there are no pauses for set changes. Adam Cork’s soundtrack provides its own commentary on that action.

But the most radical gesture, as the theatre world tries to emerge from the terrible losses of the last 15 months, is producer Bill Kenwright’s ambition to put the Theatre Royal, Windsor firmly on the map as a producing theatre. Windsor has never quite seen a press night like the one it got last night for Hamlet; every national critic was in attendance. And audiences, finally thanks to the lifting of lockdown restrictions under Stage Four of the government’s roadmap, was also at full capacity for the first time in 15 months. With a cast and production like this, I doubt there’ll be an empty seat in the house for its entire run (though restrictions may yet be brought back in with the pandemic figures on the rise again).