Last Friday, Stephen Sondheim — Broadway’s musical theatre’s greatest innovator and powerhouse over the last seven decades — left us, after 91 years, in the midst of writing another show that he revealed only weeks ago on Stephen Colbert’s The Late Show that he was in the midst of writing a new musical, called Square One that he was writing with playwright David Ives. “With any luck we’ll get it on next season,” he told him.

Though it seems greedy after all he produced to want something else, the biggest immediate sadness of his passing was that this won’t now come to pass, unless he has authorised Ives to continue without him. In one of Sondheim’s greatest musical masterpieces about the art of creation itself, Sunday in the Park with George, the title character, the impressionist painter Georges Seurat, is asked: “Give us more to see.” And with Sondheim, we want to ask: “Give us more to hear.”

Sondheim was generous with his gifts — and also with his time, nurturing countless younger artists; over the weekend, I’ve lost count of the number of Facebook tributes I’ve read from composers, actors and even critics whose lives he has touched personally.

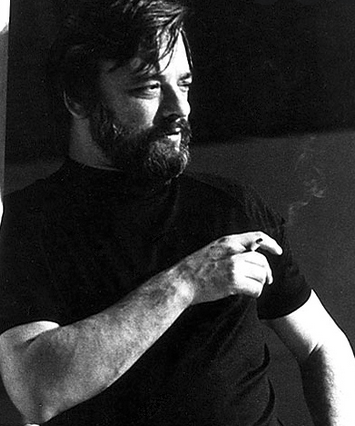

I’ve had a few fleeting fleeting encounters with him over the years, and one more substantial one, starting with the first Sondheim musical I ever saw in its original production on Broadway, Sunday in the Park with George in 1984; the second time I went to see it I bought a standing ticket at the back of the stalls at the Booth Theatre, and at the curtain calls I looked over my shoulder and there was Sondheim, watching it too. I chased him afterwards into the foyer and asked him to autograph my Playbill, which he did without complaint but also without comment.

Then, in the early 1990s, I co-founded the still-thriving Stephen Sondheim Society, with a friend Steve Aubrey; during the early years of the Society, I edited a regular members’ newsletter devoted to him, and one of our proudest achievements was to present a reading of Saturday Night, his previously unproduced early musical which had been heading to Broadway in the 1955 season but was scraped when its producer Lemuel Ayers died suddenly. at London’s tiny Bridewell Theatre. Sondheim, who was in town to attend a revival of another of his shows, actually attended and participated in a members Q&A around it after. (The theatre was subsequently granted the rights to present its world professional premiere, the first time a London theatre had premiered a Sondheim musical, in 1997).

At one point during this period I asked him for an interview for our newsletter, and he called me at my office. I’ll never forget the receptionist saying, “I have someone who says he’s Stephen Sondheim on the phone for you.” After the call, I went back and said: “It WAS Stephen Sondheim!”

But my most auspicious Sondheim encounter was on October 28, 2004, when Sondheim was due to participate in a NT Platform performance that evening, prior to a performance of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum that was being revived there at the time (pictured below). I had, of course, already bought a ticket to be there; but in the late morning, I got a call from the NT: would I actually be able to host it?

It was extremely short notice, and I was already heading to a radio studio to take part in a live broadcast, so I wouldn’t have much time to prepare; but I agreed. At least I wouldn’t have time to worry too much!

That afternoon, I met Sondheim properly for the first time about 30 minutes before going onstage. Sondheim, of course, had done this kind of thing many times before, and was well-schooled in fielding the usual questions; I hope I offered a few unusual ones. The next day, I got a message from his long-term London friend and collaborator Jeremy Sams (who had directed the original West End production of Passion), to tell me the boss said I did well!

Here is the transcript of our conversation, as subsequently gently edited by him.

MS As well as A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum here in the Olivier, which you’ve just been to see the matinee of, there is also in London a production of Sweeney Todd, which I believe you’re going to tonight, and Broadway this year has already seen productions of Assassins and The Frogs; there’s a production of Pacific Overtures about to open this month, and the last few weeks have also seen a revue of your work, Opening Doors, at Carnegie Hall, as well as a tenth-anniversary concert performance of Passion. So there’s a lot going on. To start with Forum – this is the fourth major London production. Why do you think it continues to be so popular?

SS Because it’s so funny. It is, and this is not an immodest statement. The book, by Burt Shevelove and Larry Gelbart, is for my money the best farce I’ve ever read or seen. It is so intricately put together, and it comes across so easily; it’s like it was written in an afternoon, it has a kind of breeziness to it. Actors who perform in it get to admire it because it is wonderfully put together – the way all the incidents are timed, the way all the trains collide – everything about it is elegant, in plotting and in the diction. The language alone – nobody notices how elegant the language is. There are almost no jokes in Forum, almost everything is a situation, and the few jokes that are there are really elegantly phrased. It’s a witty thing. Because of all those things, it’s a very hard show to destroy. Even when schools do it, it’s pretty funny. All you have to do is play the play, and it works. It’s because it took four years to write; for most of those four years we didn’t work on anything else, and it shows.

MS You saw it today – what did you particularly like about this production?

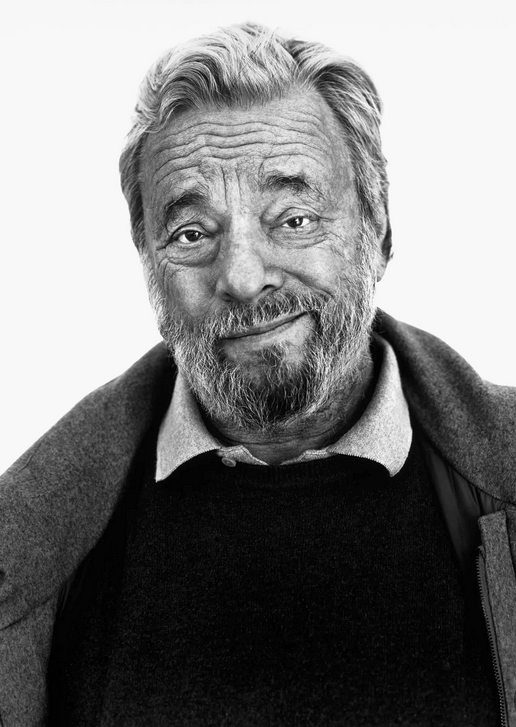

SS My favourite moment was Miles’ entrance. For those who haven’t seen it, I don’t want to spoil the surprise, but Miles Gloriosus is the braggart warrior, played by Philip Quast [pictured above], and you hear him offstage saying, in a booming, stentorian voice, “Watch out there, I take large steps!” And he does. It’s really inventive and funny. Burt originally did this show when he taught at Yale, and did it with undergraduates. He took one play of Plautus, namely Miles Gloriosus, the Braggart Warrior, and he wrote that line – “Watch out there, I take large steps!” – and cast the warrior with a fellow who was five foot one.

MS Philip Quast was your original George here at the National in Sunday in the Park with George, which is what began your association with the National, and you’ve sort of become the house musical dramatist here. You’ve created one original work for the National, which was a song for the Chain Play.

SS Oh yes, indeed. I wasn’t here to see it unfortunately.

MS It was the 25th anniversary of the NT, and they commissioned a bunch of playwrights to write something as part of a Chain Play. You wrote new lyrics to ‘Something Just Broke’.

SS Yes, it was a song that had been cut from Assassins, and I wrote new lyrics for it.

MS Talking of cut songs, in this production of Forum we’ve lost ‘Pretty Little Picture’.

SS Not from the overture of the second act, you’ll notice…

MS Do you know why that’s gone?

SS I wasn’t here, so I think you’d have to ask Ed Hall and Des Barrit. It’s a song I like very much, but it tends to hold up the action. The problem with writing songs for a farce is that once the farce gets going, you don’t want to stop for a song, which is why there’s almost no singing in the latter part of the second act, because that’s when all the pieces start being intricately arranged and rearranged. The songs are almost all in the expository part, the first half of the first act, when what you want to do is sugar-coat the exposition as much as possible. As in many farces, the first half is all the set-up for the second half. The first half really exists to set up the second half, and one of the ways of getting exposition across painlessly, one hopes, is by singing. And one of the pieces of exposition is Pseudolus trying to persuade Hero and Philia to go – ‘sail away from the harbour’. It can be accomplished in one line, but we though it would be fun to sing it. It was a song that was in the New York production but has not been in any production since.

MS The productions do tend to be quite malleable, don’t they, I mean Whoopi Goldberg took over from Nathan Lane Iin the most recent Broadway revival.

SS The production isn’t so malleable, but the casting can be. Burt called the show ‘a scenario for vaudevillians’, and he really meant that. He really wanted vaudevillians as opposed to actors.

MS The current London Sweeney Todd, which you haven’t seen yet…

SS …I’ve seen a tape of it.

MS It’s the smallest production it has yet had.

SS Yes, it’s even smaller than the one that was at the Cottesloe.

MS I’ve heard it described as ‘The Toddler’ or ‘Teeny Todd’. This is the fourth major London production we’ve had; it was also producedd the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden last year. It’s an incredibly popular show.

SS Well it wasn’t when it was first done here. It was not popular at all. The press did not like it. I think what happened was that they thought “who are these Americans to tell us a British story?” The story of Sweeney Todd, the plot, the idea, even just the phrase, was completely unknown in America up until we did the musical. I meant it as my love letter to London, because I love London. I saw Chris Bond’s play out at Stratford East in 1973, and thought it would make a musical. I’m not quite sure why the original production was as poorly received as it was, but it was not a success. Then when Declan Donnellan did his production in the Cottesloe, which was brilliant, it was well received. I don’t know what happened to British taste over the period of time, because the show wasn’t changed at all, except for Declan’s work on it.

MS We’ve also had a promenade production, at the Bridewell. Did you see that?

SS I missed it by one day. It sounds terrific. The audience was ushered into a vault-like room, lit only by slit windows high up, and when the show started, the doors to the room were shut and the entire audience was trapped. There were very few seats, and bodies started to drop all around you, blood splattering – it’s my idea of what the show’s supposed to be!

MS The Bridewell is also responsible for the only British premiere you’ve had of one of your shows – Saturday Night.

SS Yes indeed, a show I wrote when I was twenty-three years old.

MS You’ve heard about the fate of the Bridewell, which is threatened with closure?

SS Yes, I’m really sorry. It’s one of the few venues that existed in London for the production of new or interesting musicals. It’s a small and intimate house, but they did wonderful work there. I saw a couple of things there.

MS Moving On also began life there, which was what became Opening Doors that has just been done in New York.

SS Yes, that’s a revue of songs, like Side by Side.

MS Is there a further life for that?

SS I think so, yes, we just did it for six performances in New York at a concert hall. It’s a revue of songs I wrote, but the gimmick, devised by David Kernan, is that the groups of songs are introduced by my voice over, talking about various subjects. What happened was that David and John Kane came to my house a few years ago and asked questions about everything from writing to living, and then they edited the tapes. There are some visuals, some photographs of me, my family, or New York City. One section will be “What is it like to grow up in New York City?”, so I talk about that and then there’s a group of New York City songs. Eventually I get pompous and philosophical, and there are some pompous and philosophical songs. That started at the Bridewell.

MS Pacific Overtures is about to be revived on Broadway. How different will this be from the original?

SS Pacific Overtures is a show that dates back to 1976. It was brilliantly put on the stage by Hal Prince, and then four years ago I was in Japan and coincidentally there was a Japanese production at the Japanese national theatre. I happened to get there with my collaborator John Weidman, who wrote the libretto, one day before the limited run was over. We went out of a sense of politeness, and were knocked out. It was directed by a man I think is touched with genius. His name is Amon Miyamoto. It was one of the most exciting things I’ve seen in the theatre, and not because I was connected with it. When I got back to the United States, I did something I’ve never done before. By nature I’m not very aggressive, but in this case I thought this show must be seen, so I hustled. I called the Kennedy Center in Washington and the Lincoln Center in New York and I said “You have got to get this show”. They both got a videotape of the production and they were knocked out by it too, so they brought it over. It was all in Japanese with subtitles. Then, over a couple of years now, we have hustled up a Broadway production with the same director, and the same staging, but in English. It will be very interesting to see whether its being in English has any kind of effect on it, because, for those of you who don’t know, Pacific Overtures is a show about the American incursion into Japan, the gunboat diplomacy of 1853. Most of the piece takes place in those months when Commodore Perry came with his gunboats, then there is a brief contemporary sequence at the end of the show. So here was a Japanese production about the invasion of Japan by America, written by Americans, performed in Japanese. The ‘Japanese box’ of it that you could feel in that theatre in Japan was extraordinary. It worked so well at Kennedy Center and Lincoln Center that we decided to take a chance and do it in the original English but with an Asian-American cast and with Amon directing it. So any of you that have the chance to be in the United States after November 12th, I highly recommend it. This man’s work is really something. It opens at Studio 54.

MS We also had a studio production of it here at the Donmar last year, courtesy of the Chicago Shakespeare company.

SS Yes, an entirely different approach, much more ritualised.

MS Do you have a preference for large scale or studio settings?

SS No, the first time I ever worked in a studio setting was on Sunday in the Park with George. I was brought up on Broadway and in Broadway houses. Off-Broadway wasn’t even invented till I was in my early twenties, and that was the first time shows were presented anywhere in New York except near Time Square. When I first started working with James Lapine on Sunday in the Park with George, he was kind of house playwright at one of the better off-Broadway organisations called Playwrights Horizons. I loved working there, because you know you’re just writing a show for the love of the show, and it’s not-for-profit theatre, in other words it’s subsidised by private subscription. It has some state funding but not much because, as you probably know, there’s almost no government funding of the arts in the United States. So these theatres are funded by audience subscribers and also by going out to get donors. It was good to know that you weren’t letting down a lot of backers who’d put a lot of money into a show. When you would do it on Broadway in the old days you would think “Oh my god, my aunt Molly is going to lose her $1500 if this show doesn’t work”. But when you do it there, there’s none of that pressure. If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. If it gets bad reviews, it gets bad reviews. There’s nothing riding on it except the love of doing it, and that’s of course why any sane writer writes – for the love of it – otherwise it’s a fool’s game. So in that way, I prefer to write for studio theatres. Assassins was also premiered by Playwrights Horizons, and so was Into the Woods.

MS What did it feel like seeing Assassins on Broadway this year for the first time?

SS Well, it’s at Studio 54, which is on Broadway but it really feels off-Broadway. It used to be a nightclub, a rather notorious one as a matter of fact, in the latter part of the last century.

MS Did you ever go?

SS Oh yes, I did. And then it was transformed into a theatre, but it isn’t exactly a theatre. It’s where Sam Mendes had his enormously successful production of Cabaret, and it is a cabaret. That is to say, when you come in on the ground floor, there are little round tables with chairs round them, and drinks, and a couple of banquettes at the back, and it feels like a cabaret. Upstairs, it’s exactly like a theatre, with rows of seats. It used to be an opera house. It has its own raffish atmosphere. We were worried that Assassins wouldn’t work there, not having a proper stage. It’s thrust like this [the Olivier], which is fine for Cabaret because it takes place guess where? In a cabaret. But Assassins worked really well there, and how Pacific Overtures will work, I have no idea, because the production uses the Japanese theatre convention called hanamichi, which is the long runway that comes down through the theatre to the stage. It’s where royalty makes their entrance in kabuki theatre. In our production it’s where the Americans enter. Japan is the stage, the Americans come in down the hanamichi. But there are all kinds of things which may make it a little tricky.

MS And The Frogs didn’t even begin off-Broadway, it began in a swimming pool. How was taking it to dry land at Lincoln Center?

SS The Frogs is an academic piece that I wrote with Burt Shevelove in 1973, it was 55 minutes long. Yale University where Burt had taught asked him to come back, and he did a production of Aristophanes’ The Frogs with the Yale swimming team in their Olympic-size swimming pool. For those who don’t know the piece, it’s about Dionysus’ trip to the underworld to bring back a writer to save the world. The creatures he meets on the river Styx, on the way to Hades, represent philistines. The notion was to use the Yale swimming team to represent the Frogs. Our production was all performed in the swimming pool, and very reverberant, which caused a lot of problems. When you came in there was a boat at the end of the pool with a man with a beard asleep in it, representing Charon. The beard was about 30 feet long, and trailed off across the water. The Frogs came in through various vomitoriums and dove in; it was really quite extraordinary. We did a concert version of it a number of years ago down in Washington, which was narrated by Nathan Lane. Nathan fell in love with the piece and asked me if he and Susan Stroman, the director of The Producers, could put this on, and if I would write some more songs and make it a full length piece. We just closed two weeks ago, at Lincoln Center. We did it on dry land, but Susan Stroman’s choreography made water on the stage.

MS Talking of more recent shows of yours, Bounce didn’t bounce to Broadway last year, and presumably you were very disappointed by that.

SS Bounce is a show that I wrote with John Weidman, it was directed by Hal Prince. We like it a lot, and the problem is that usually, when you stand at the back of a theatre watching a show that’s not quite working, you can feel what the audience is feeling, what they’re disappointed in, what they’re not getting, why they’re not having the kind of good time you want them to have, why they’re not involved, whatever it is… Then you go about fixing the show. Forum is a great example of that, it was a terrible disaster out of town, when it was first done, it almost closed out of town because audiences hated it so much. We worked on it, mostly by giving it an opening number. The guy who directed Forum originally was a legendary Broadway director named George Abbott, and what he was famous for was farces, musicals, comedies. He was also famous for being called in for plays that were in difficulty out of town. He was known as a ‘play doctor’. We opened in New Haven, and on about the third or fourth night, when the show was clearly landing like a dead fish, George Abbott turned to Hal Prince and said, “Hal, you know what? You’d better call George Abbott in.” We thought the play was screamingly funny. The audience didn’t. What it needed, and what changed it around entirely, was the opening number. I wrote ‘Comedy Tonight’ in Washington, which was the other city we visited before coming to New York, and it was a number which told the audience what to expect. I had written an opening number which was quite charming, and what George wanted, but the trouble was it didn’t prepare the audience for the sort of low comedy shenanigans that went on. They expected a lighthearted romance, they weren’t ready to laugh and they weren’t ready for the vulgarity that was to follow. In the case of Bounce, we stood in the back and we all were having a good time, a very good time. The audience wasn’t having a bad time, but the plane didn’t take off. It didn’t exactly lay there, the soufflé would start to rise, then… I can’t be more articulate than that. So what we’ve decided to do is let it sit for a while and then maybe just look at it again and see what happens. It’s had a long history, we started the first draft maybe nine years ago, and we’ve been working on it sporadically and with some persistence, and with a number of different directors. Each director had a different take on the show, and I think there may be a case of too many cooks. it started as a real farce, a cartoon, a Hope/Crosby movie. It’s about two brothers, and the relationship between the patsy and the finagler. It’s changed character over the years and I think maybe the original intention was the right one.

MS Perhaps a London production?

SS It’s a very American piece, I’m not sure if the British could relate to it. It’s primarily about American enterprise and the so-called pioneer spirit. It covers a period of time from the gold rush in the 1890s through the Florida boom-and-bust in the late 1920s, so it covers a particular period of American history that is familiar to Americans.

MS The National have done quite a few of your shows. Is there any particular one you’d like them to do next?

SS Oh my goodness, I’d have to think. There was almost a production of Follies here a year and a half ago, I’d love to see that here, in this theatre. You look around at this theatre and though it’s not a decaying theatre, the size of it would be nice.

MS Before I open it up to the audience, I want to quote Jeremy Sams, who interviewed you here ten years ago. He said about you, in an interview, “I venerate him as a human being and as an artist. The only thing I have against him is that he’s covered every exit and nailed it up, and it’s very hard for everyone else. He’s as big to musicals as Wagner is to opera, and the history of musicals will never be the same again until he’s written out of it, and that will take a century.”

SS He’s a friend!

MS But is it hard to carry this legacy?

SS I don’t think of that. I don’t see myself from a bird’s eye viewpoint. It’s very complimentary, but you know, the good news about what’s happening to musicals is that there’s much more talent out there, both in New York and in London. People have really inventive ideas about how to use the stage, how to use music, how to incorporate pop music into a musical theatre tradition, ways of involving an audience that are unconventional, but there’s no place to put them on in London, and no money to put them on in New York. The theatre-going public in New York is not interested in anything that they haven’t seen before, and I fear that that’s happening here too. This phrase, the “dumbing down of America”, the whole culture is getting less interesting, and theatre-going is very expensive. People are less willing to take a chance on something that either they haven’t heard about or isn’t a hot ticket. They’d much rather see a revival of a show they really like, or a compilation of songs by, say, Abba – Mamma Mia is a huge hit. They want to feel that the huge amount of money they have to spend to go to the theatre and have dinner, particularly if they come from out of town, is worth it. The same is true in opera – for every new opera that is done, there are twenty-seven Puccinis, thirty-seven Mozarts, and ninety-seven Wagners, that’s what the audience wants. When they do do a new opera, the house is half full, and it’s just as expensive to do a new opera as to do Bohème.

Audience question

Something that I think hasn’t been mentioned in previous Platforms, and people may not know about, is your career as a crossword-setter for the New York Times. I was wondering how this ties in with your ingenious lyrics?

SS It wasn’t the New York Times, I used to compose crossword puzzles for New York magazine. It was the first year only that they did it. One of the founding mothers of New York magazine is the well known author and feminist Gloria Steinem, who is a friend of mine. She said they were starting this new magazine and wanted a puzzle page. I said the only kind of puzzle I was interested in was cryptic puzzles, which were completely unknown in the United States at the time.The kind of puzzles you all take for granted in all your papers had never been done before 1979 in the United States, all the puzzles were simple definition-and-answer, sometimes with quite obscure words, like “a three-letter word for an East Indian betel nut”. But I was brought up on British puzzles from the Listener magazine and the Sunday Observer Ximenes. I’d loved cryptic puzzles since I was in my early twenties, in fact it was Burt Shevelove who got me interested in them. So I did this for a year, and I’m happy to say that now cryptic puzzles are done all over the United States, in many publications, and I take full credit! Not modest about that at all.

As far as its relationship to what I do as man’s work, I’ve always considered lyric-writing a form of puzzle. You have so many syllables, so much time to put them in, and you have so many thoughts, and as soon as you start rhyming it’s a matter of alignment. It’s analagous to the symmetry of a crossword puzzle. The nice thing is that a puzzle has a solution, a lyric doesn’t. As Paul Valery said, “A poem is never finished, it is abandoned.”

Audience question

What is your favourite new musical from the last three or four years, here or in New York?

SS The last musical that I saw that knocked me out was quite a while back. It was called Floyd Collins and it was on here at the Bridewell. It was by Adam Guettel and Tina Landau, and if you don’t know it, get to know it.

Audience question

Do you have any plans to put on Putting It Together in the West End?

SS No. Putting It Together is another revue of work of mine. It was done first at Oxford (with Diana Rigg starring, as a matter of fact), then it was done in New York with Julie Andrews, and then was put on again with Carol Burnett. The new revue that David Kernan has devised is, I think, a more interesting one. Putting It Together was something Julia McKenzie and I put together. It attempted to make a story out of disparate songs from different shows, and unfortunately there’s a feeling of effortfulness. It’s hard to tell a story that encompasses a song from Into the Woods and a song from Sweeney Todd, and a song from Company with a group of characters that’s supposed to be consistent. I think this new revue will replace that.

Audience question

How do you react when people say Forum is sexist? And do you think it is?

SS No, I don’t. I hadn’t heard that. Vaudeville humour was sexist, of course, and there is a vaudeville tone to this, but in fact if you’ve got to lay the blame at anyone’s feet, it’s Plautus. This is very faithful, it’s based on four plays.

Audience question

I recently came across a song of yours I’d never never come across before. It’s called ‘I Remember’.

SS ‘I Remember’ is a song I wrote for a television show called Evening Primrose. As a matter of fact it’s going to be done in a concert version here next year, I think at the Theatre Museum. It’s an hour-long piece based on a rather bizarre story by an elegant horror-story writer named John Collier, a British writer. It’s about a fellow who, to get away from the world, decides to hide in a department store and live there, because he realises you can carry on a complete life in a department store, as long as you’re not seen. Then he finds he’s not the only one with this idea, there are whole groups of people. They’re not allowed to reveal this because they would be caught and thrown out, so if anyone leaves the society, they’re turned into a mannequin. Jim Goldman, the fellow who wrote Follies, and I did this in 1967 for a series called Stage 67 on ABC. It has four songs only, and the second song is called ‘I Remember’. It’s sung by a girl who works as a sort of maid for all these people. She’s only eighteen years old but has lived all her life since she was four in the department store, since her mother lost her in the hat department. It starred Anthony Perkins as the poet who hides away, and it can be seen, if anyone wants to see it, at the Museum of Broadcasting in New York.

Audience question

What advice would you offer to young musical writers who are facing the problem that there’s not enough money or theatres?

SS The advice I can offer is sort of empty, in the sense that I believe the only way to learn writing, at least for the theatre, is to write for the theatre. Obviously there’s a certain amount of academic training and certainly reading of plays can help, but it is a practical profession. Therefore I always advise people, because it’s the advice that Oscar Hammerstein gave me, to write something and put it on some place, even if it’s a neighbour’s livingroom, even if it’s just read by a cast and you play the piano and just listen to it, you’ll learn a lot about writing. Practical advice about how to get a show on differs from America to London. There’s an organization of young writers here called the Mercury Workshop. Cameron Mackintosh established a Chair of Musical Theatre at Oxford in 1990 and I was the guineapig; we had a seminar of thirteen songwriters, and out of that seminar came the Mercury Workshop. They decided not to let the notion of the group die there, but to keep it growing. Now it has I think 130 members, people who meet and listen to each other’s work. I was talking to them last night and saying that the problem for young writers in London is quite different from that in New York. There is no equivalent of off-Broadway here. Songwriters in New York have just as much trouble getting their work heard as they do here, but what can happen is that a piece can be done off-Broadway and have what they call an open-ended run, as opposed to four weeks or six weeks. In so doing, if it runs a while, it can attract not only a public but professional interest. There’s a show here at the Shaftesbury, Batboy, which came from off-Broadway. So there’s a chance that a show can then go somewhere. In London there’s no such venue. Whatever you call theatres like the Almeida, Tricycle, Royal Court, plays can only go for limited runs. They might transfer to a West End house, but nothing gets a chance to run for a while. Cameron Mackintosh is making a transfer house now on Shaftesbury Avenue, for perhaps 500 seats, and one of its purposes is going to be that if a piece isn’t ready or shouldn’t go to the West End (because there are certain pieces that shouldn’t go to the West End) it has a chance to run and the audience that it can appeal to will have a chance to see it. That’s the thing that’s sorely lacking in London for young writers – showcase places. You may have heard of a show called The Fantasticks that ran for 37 years at an off-Broadway house down in the village that only sat 100 people, but for thirty-seven years. The result was that of course productions of it were done all over the world and the two guys that wrote it are as rich as you can get, just from a 100-seat house.

MS And of course that studio theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue is to bear your name…

SS I didn’t want to say that, but I’m flattered, and embarrassed.

Audience question

If there was one piece of work of yours that you would like to be heard in a hundred years, what would it be?

SS I have to reply immodestly that I like a lot of them. I really don’t have a favourite. I’ll amend that answer a little bit… The show that comes closest to what I and my collaborator would call perfection, meaning that it’s exactly what we intended and we can’t think how to improve it, is Assassins. That’s the one.

Audience question

How did you come to be involved in scoring the film Reds?

SS This is a long story, but I’ll cut it short. Warren Beatty wanted a romantic theme, and he also wanted the ‘Internationale’ because he likes it a lot, the communist march, which is a tune I don’t particularly like. So I kept writing what I thought was moody, romantic music. He was being nice about it, but I could see I wasn’t really pleasing him. I could see that what he really wanted was A Tune. So I wrote this tune, and asked him not to play it to anybody, recorded it on a mini tape recorder, the kind you throw away. It was orchestrated in many ways, for piano and orchestra, for wind section, for strings. And Warren kept rejecting all these orchestrations, saying “It just doesn’t have the feeling of what Steve did…” I said, “It never will, Warren, just hear it fresh.” I had been angry at him for playing that little tape for people because it was midnight when I recorded it, I was very tired, and my fingers hit the cracks. Anyway, the end of the story is, I go to the first screening of the movie, the theme comes on, and what has he done? He has used my tape! If you listen carefully to the first entry of the theme, you will hear that. And then, there’s a line where the hero says to the heroine, “I’ll be back for Christmas.” There’s a famous song of Frank Loesser’s called ‘I’ll be home for Christmas’ and it starts out in exactly the same way. Someone in Warren’s cutting-room pointed this out to him, and he came to my house, looking ashen, and told me. This is a song I’d never heard, but I said, “Listen carefully to what I’ve done”. And what I’d done was to take the tune of the ‘Internationale’, reharmonised it and made it into a lovesong.

Audience question

Do you prefer actors who sing or singers who act?

SS I tend in casting to go for actors, but there are certain shows, like in Sunday in the Park with George, the two leads should sing very well because it’s part of the acting. If they’re not singing well, the show loses an enormous amount of its emotional impact. Which is curiously less true, I think, of Sweeney Todd. That show can be forcefully delivered, I don’t think you have to sing it as well, but Sunday is a show where I would lean a little towards the singing. And certainly Passion. The three principals in Passion, if they can’t sing, they can’t act it. What I meant it to be was one long song, a song for three people. But generally I go for actors, if they can carry a tune. Unless you need a huge amount of volume or they sing a lot of complicated music, delivery is what counts.