Audiences go to the theatre for pleasure, not work; critics need to remember that their work is someone else’s pleasure.

Critics are in a strange position: going to the theatre is for work. But we must never forget that for most, it’s for fun. And enlightenment and to be challenged, too, but primarily, it is for pleasure. And as a critic, the most important thing is to (try to) retain that sense of pleasure, not penance.

I’ve just had a couple of nights back in London, staying at a hotel booked through Air BnB next to Paddington station, so therefore suddenly a tourist in my own (former) home city of the last 40+ years. Staying in a hotel alone makes it feel different; and it was actually a welcome way to re-experience London without the commitment of living there, but at the same time knowing that I’ve got a beautiful home to get back to in the countryside afterwards.

Part of the reason I was in town — and will be back at least once a week for a similar overnight stay, or more — was to catch some theatre. But (and here’s something that is hardly a novel experience for me) it wasn’t JUST for work: something that theatre critics need to hold onto and remind ourselves of constantly.

A different calibration applies: these are shows I choose to see for my pleasure. I will often, as I did twice over on Wednesday, buy my own tickets. This means I experience what a regular theatregoer does in navigating things like online box offices (and endless waiting queues when booking first opens) I also experience different views, as my budget affords, not what the management would choose for me (like the one from the upper circle of the London Coliseum I had on Wednesday afternoon for a preview of Hairspray, pictured below).

As it happens, I’ll be back next week for the opening, when I’ll be in a reviewing seat, (very possibly) in a better location but therefore not being able to simply surrender to the pleasures of a show I’ve long loved but watching it through a different lens entirely, assessing it in the historical context of the now-numerous times I’ve seen it before.

I’ve always tried to integrate shows I see for reviewing purposes with some more that I just go to for myself; of course, this doesn’t mean that I also don’t actively enjoy many of the shows I see FOR WORK, but just that by not making it always ABOUT work, I can also remind myself that I’m there for the sheer love of it.

I duly saw five shows in the space of my three day visit, only one of which was for a review (No, I can’t help myself); and tomorrow I’ll be back in town for the day only for two more (cut down from the three I was originally planning; one of which is for review, the second by request of the producer and the third, the one I’ve cut, was for me). I’ll be back again next week from Tuesday to Thursday, to catch the openings of Hairspray at the Coliseum, a press double day helping of Constellations to at the Vaudeville (seeing the first two of the four casts that performing Michael Wynne’s contemporary masterpiece) and a fringe revival of a revue cycle, Starting Here, Starting Now, that I’ve long loved.

All of these are by invitation of the theatres concerned; there are well-established protocols that mean that critics traditionally only review shows when they’re actually invited to do so. This is thanks to a “gentleman’s agreement” between theatre managements and critics, built up over generations, in which theatres are given the power to decide when they are ready for critical appraisal, and in return extend hospitality to critics to attend when that day is reached.

But sometimes managements play hard and fast with their own rules; as when Broadway’s Spiderman — Turn Off the Dark repeatedly delayed their press opening, despite charging theatregoers full price to actually attend what was effectively being deemed a work in development, that New York critics eventually lost patience, bought tickets, and reviewed the state of the play around five months into “previews’. (It would finally officially open some 8 months after it had begun performances).

But usually the current system works to mutual benefit: producers and creatives are given the space to ready their productions in front of paying audiences that do not include critics, so therefore are safe from their prying eyes and premature judgements, and the press itself knows where it stands, with no publication stealing a march on others to get an earlier opportunity to publish a review.

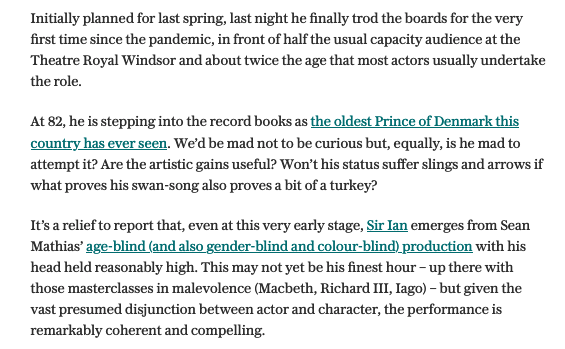

So it is the RIGHT thing that critics play by the rules, both out of respect to the creative process of the shows and to EACH OTHER. But on Tuesday this week, we saw a fundamental breach of this, when the Daily Telegraph published a review by its chief theatre critic Dominic Cavendish, of the first preview performance the night before of Ian McKellen’s new production of Hamlet, at WIndsor Theatre Royal.

As he reported (and reviewed):

Never mind that Cavendish says here it may not (yet) be McKellen’s finest hour — but it was actually his FIRST hour. It was not intended, or available, for review yet.

Of course, I can appreciate the temptation to wade in with the first opinion on what is undoubtedly a significant theatrical moment; but it also muddies the waters significantly for what passes as a review. And it sets all the other critics — who were originally invited to attend next week (on June 30) but whose invitations were subsequently changed to July 20, after the roadmap on theatre reopening to full capacity was revised last week — at a new and hostile disadvantage. Others will now be asked by their editors why THEY haven’t covered it.

This is not the first (and it won’t be the last) time that such a breach of protocols has occurred; back in 2015, The Times sent (then-rookie) critic Kate Maltby to review the very first public performance of Benedict Cumberbatch’s Hamlet at the Barbican Theatre. They basically threw her under the bus, given that she was only doing what her editor asked her to, and as a young critic, new to the paper at the time, she didn’t necessarily have the power to resist.

But the backlash was swift, fierce, unanimous and damning: Maltby HAD breached the etiquette. It is frankly astonishing that Dominic Cavendish — one of our very best critics writing today, whose COVID coverage in particular has been exemplary – should have sacrificed his own integrity for a quick editorial advantage on his critical colleagues. Still, it’s a trick you can only pull off once: now he will no longer be trusted to ever abide by the rules again. (Trust, once lost, is very hard to rebuild).

Meanwhile, for the avoidance of doubt, I am going to readily admit that on Wednesday night I headed myself to the first preview of Nina Raine’s new play Bach and Sons at the Bridge Theatre (pictured, in rehearsal by Manuel Harlan, is Simon Russell Beale as JS Bach and Samuel Blenkin as one of his sons, Carl).

But I went as a PAYING customer; I did not solicited a press ticket by misrepresenting my intentions about what I intended to write about. It so happens I’m only in London now on limited dates; and next Tuesday’s official opening clashes with that of Hairspray at the London Coliseum, and I can’t be at both. Plus my husband was already in London with me on Wednesday; he is a big fan of Simon Russell Beale’s (who, after all, isn’t? He’d even bought HIMSELF a ticket to see his Prospero in the RSC’s THE TEMPEST a second time a few years ago…..).

So I simply bought two tickets. It also set me free of the necessity of having to negotiate with the Bridge’s press rep for a ticket (always an ordeal); and therefore not having to be dependent on their ‘kindness’ (actually, their job, but that’s another story) to secure one. I was there on my terms, not theirs. And best of all, I could watch it entirely unencumbered by having to think about what I’m going to have to write about it afterwards. So it was just a win-win for me!

And while first nights have their own specific expectation and frisson, first previews can also be highly-charged events, not least with a world premiere: the audience there is literally the first PAYING audience to attend (some shows may have had an invited dress rehearsal or run-through for friends, family and other industry insiders before that).

Having bought and paid for a ticket, of course, I’m officially free of any embargoes against commenting on what I saw; but I’m still honouring the press night before I do so. That’s partly out of respect for my colleagues, to maintain a level playing field when they come to write THEIR reviews; but also out of respect, above all, to theatre-makers and managements for the opportunity to get their shows “critic-ready” before we ‘officially’ arrive. It would serve no one if I suddenly followed Dom Cavendish’s example and went rogue in jumping the critical gun; I’d just get the backs up of my colleagues, and friends in the industry, and undermine a system that mostly already works.

If a critic occasionally seeks to disrupt that system, as the Telegraph did this week, or an unhelpful press rep forces me to buy a ticket when they won’t accommodate me, I’m going to be the bigger person and not rise to the bait and hope that two wrongs will ever make a right.