On Monday, leaders of three American entertainment unions — SAG-AFRA, Actors’ Equity Association and the American Federation of Musicians Local 802 released a joint statement condemning workplace harassment, bullying and violent behaviour.

“Every worker deserves to do their job in an environment free of harassment of any kind, whether that harassment creates a toxic workplace or, certainly in the case of sexual harassment, when that behaviour is also against the law.”

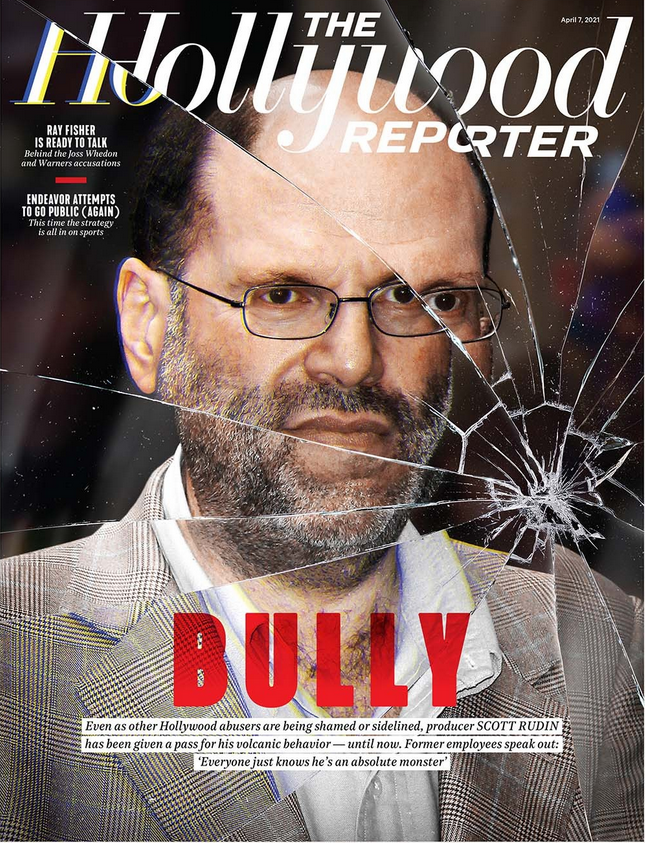

The statement did not actually mention the person whose reported behaviour triggered it, namely producer Scott Rudin, after a Hollywood Reporter feature made public what many in the industry have known about for years: his legendarily abusive treatment of employees and the people he sub-contracts to work for him, like press agents and ad agencies.

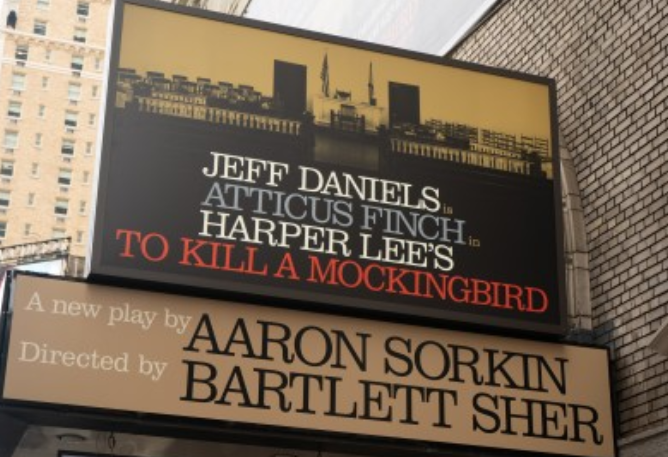

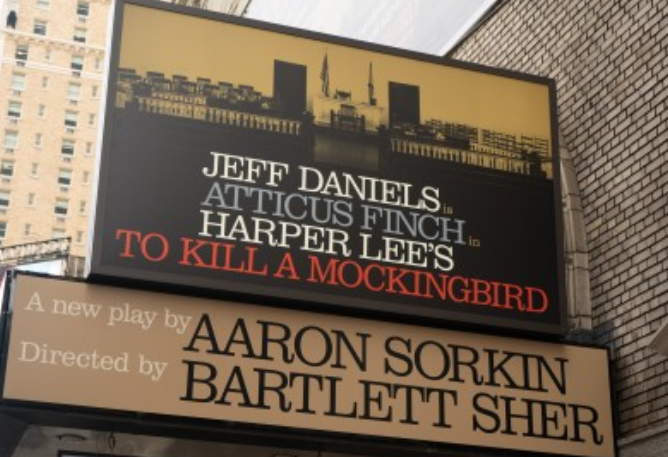

Occasionally some of this would come to the surface, as when one of the latter, SpotCo, litigated for unpaid fees last summer, amounting to some $6.3m (which was clearly quite a line of credit being extended to him). And in 2019, he caused an international theatrical incident when he forced community and regional productions of an alternative, earlier stage version of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird to be summarily cancelled, despite their holding valid licenses to produce it that had been obtained in good faith, by asserting the exclusive rights he’d been granted for a new Broadway stage version. London’s Open Air Theatre was also affected, as they were forced to cancel a tour that had been booked of their successful revival.

A conspiracy of silence — driven by fear — has effectively enabled his behaviour for years. And when, last week, I sat sobbing at my desk at 4.30am as I read the twitter account by the brother of a former assistant of his who had committed suicide, I knew it was time to break the silence myself.

On Saturday, I did just that, with this column.

As I wrote there, I’ve had quite a close personal connection to Rudin over the years, particularly through a friendship I’ve had with his partner John Barlow, a former Broadway press agent, that long predates their relationship. And like any and all critics, I am of course dependent on Scott’s hospitality for access to what would otherwise be not only expensive tickets to his shows but also invariably tough tickets to get, too.

I also wrote,

“I realise that in writing this I may well burn a bridge here and never gain access to a show of his in the future, but here’s the thing: I’m not sure I want to be beholden to him ever again. It comes at too high a price. A very good friend of mine who lives in New York and first shared the Hollywood Reporter story with me told me that he is no longer going to support Rudin shows; its the only protest he feels qualified to make, to not given his entertainment dollars to support a serial bully. And I feel the same now.”

Ultimately, in other words, you have to take a stand. I no longer have a bullying editor to answer to who, in the past, has tried to reign me in when I’ve gone ‘rogue’ in calling out bad behaviour in the industry; when an associate director at the Young Vic publicly tweeted of a former critical colleague of mine that he was “TRASH, TRASH, TRASH”, that editor cautioned me to cool off, because it was going to look like I was the bullying one, and this might reflect badly on his publication.

I’d reported that incident when it occurred to the Young Vic’s artistic director Kwame Kwei-Armah, who promised to get back to me; a meeting we arranged was cancelled when his father fell ill, but never rearranged. I still don’t know if there were any consequences for that outrageous public show of contempt for a then-prominent member of the press.

My current position as a freelance critic running my own platform is giving me a lot of freedom to now call out behaviour as and when I see it. On a personal note, I have spent much of the last year investigating my own childhood trauma through a 12-step programme that deals with family-of-origin issues, and have, as a result, been inventorying my own role in those dynamics.

As those who know how 12-step programmes work will already be aware, the ninth step involves making amends to those we’ve harmed. This includes ourselves. In other words, we take responsibility for our own part in the harms that have been caused, to help free ourselves from the shame and blame of the past.

You don’t inventory other people’s behaviour, of course, only your own. But having learnt from this process just where I’ve gone wrong, I am now no longer hesitant to speak up when I know that others have done me or others wrong, either.

I’m no longer afraid of bullies. And of course, I am doing my best not to be one, either. But sometimes you have to protect others, not just yourself, by speaking up. It would have been easy to have been timid in the wake of the Rudin revelations and not rock that boat; to let others take that risk. But sometimes you need to take a stand.

By the same token, I’m not the only critic in town who finds that dealing with a particular West End press representative is invariably a painful, sometimes humiliating process, who always puts as many roadblocks in the path to getting access to the shows their company represents as possible.

But of course they get away with it, because West End tickets are expensive, and we don’t really want to have to buy them so we can write about them, which is exactly the job the publicist is there to help facilitate. Knowing however, their penchant for exercising power over critics by blocking that access, I took steps last Christmas to make sure that I would be able to see a show regardless of what I predicted their behaviour might be.

I bought a ticket for the first preview of a show they were representing; I then requested a press ticket in the normal way. I was disappointed, but not surprised, to be turned down. So I informed their client that I had a ticket for that first preview, and would be reviewing the show at that performance, posting my review by 7pm that evening.

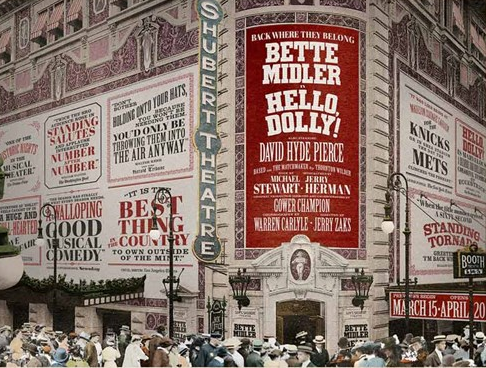

The producer answered me by return, requesting me not to do that. I replied that, since his appointed press agent had refused to accommodate me, as I suspected they would, I had taken my own steps to make sure I could cover it, even if it had cost me £80 of my own money to do so. He, in turn, promptly overrode his press agent, and promised to refund me the cost of my ticket, and allocate me a pair of the best seats available for a performance of my choosing. (Sounds familiar? Yes, that’s exactly what Scott Rudin did to me, too, after I bought a ticket for his production of Hello, Dolly!, after his appointed press agent had refused me access, and he, too, had said he had no inventory available to accommodate me).

I accepted this offer, and was booked into a performance the night before the official press night (as I didn’t want any issues with running into the press agent concerned). As it happens, that press night got cancelled when the December Tier 3 lockdown in London kicked in that day, and the show didn’t open to the press after all. But neither did I see it the night before, which turned out to be the last night of the run, as my husband and I had planned to go to the Lake District (that was in Tier 2 restrictions) at the end of that week — and with the lockdown arriving early, we took the decision to extend our stay and head there early on the Tuesday, so we would arrive there before travelling from tier three to two would no longer have been allowed.

So I cancelled my tickets to that show after all. In fact, I wished I’d stuck to my original plan and gone to that first preview, because then at least I would have seen it. But it was also just as well that we did get to the Lake District at the earlier time on Tuesday, checking into the hotel around 9pm that night, because we definitely got there before travelling there would no longer have been allowed. (A few days later, having tweeted I was there, we got a visit from the local police: someone had accused me of breaking the lockdown as a result of my social media posts from there, and they were forced to come calling. Of course, they were able to establish from the hotel that we’d arrived ahead of the lockdown.)

That turned out be the only holiday we had in all of 2020 so it was worth sacrificing one show for; what isn’t worth sacrificing, however, is my mental health as I worry about whether I’m going to be snubbed in the future by the same press agent. So I’m now making my own arrangements to cover their shows in future, if and when I need to.

I am, in short, cutting out the middle (wo)man. I am going to request tickets in the normal way; I don’t , of course, expect preferential treatment. But if I’m turned down, I will again go on my own steam, and maintain my own integrity — and independence.

If you can’t join them, beat them.