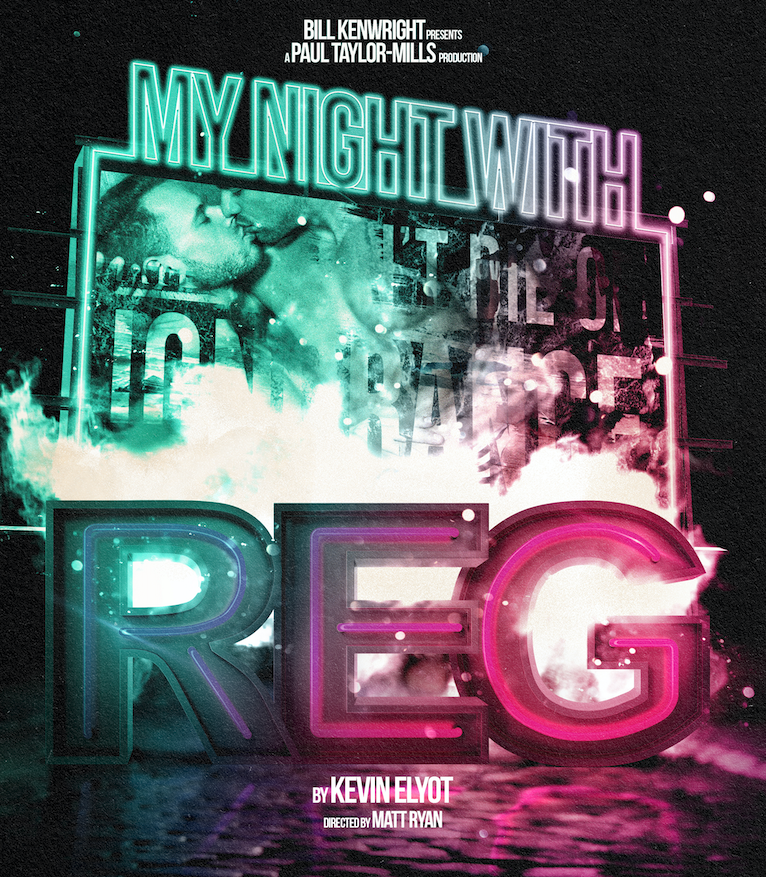

I saw the 1994 world premiere of Kevin Elyot’s My Night with Reg both at the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs and its subsequent West End transfer, with a cast led by David Bamber, John Sessions and Anthony Calf as three university pals and their variously unrequited and overlapping desires in the age of AIDS.

Back then the play was a report from the frontline of an unfolding health crisis in the gay community, where HIV/AIDS could still be a death sentence. A one night stand in Lanzarote, with a mortician from Swindon, could kill you.

We’ve lately been powerfully reminded of this period in Russell T Davies’ extraordinary series It’s A Sin. But revisiting the play now, in a tender and exquisitely yearning new production from director Matt Ryan, is to experience this heartbreaker of life and loss and friendship and family not just as a time capsule of a particular period of our lives but as a timeless classic, an intricately patterned play of layered and deeply poignant inter-relationships.

Its those shifting textures and unspoken tensions between all of the play’s beautifully charted long-time friendships that Ryan’s production skilfully articulates. Paul Keating’s painfully single Guy (pictured above; all images by Mark Senior) — approaching 40 as the play begins, and never having established a meaningful emotional relationship apart from with an occasional phone sex mate he has never met — is the person everyone pours their hearts out to; but his own big secret, of his long unrequited love for Daniel, is one he can never share with the object of his desire. It’s Rattigan-esque in its desperation and avoidance.

Keating, an underrated but immensely versatile actor who has also starred in musicals, is chameleon-like in how he has immersed himself in the character’s self-deprecation; he succeeds in being simultaneously invisible to the others yet also the least narcissistic of them and therefore the most loveable.

As John, who lives off an inheritance and will acquire another one in the course of the play, Edward M Corrie (pictured above) has just the right languor and his own defensive isolation that’s calculated to break hearts, especially Guy’s, but also in turns out, his own, too.

And Gerard McCarthy’s art dealer Daniel (pictured above right with Paul Keating’s Guy), in a relationship with the unseen Reg at the start of the play, is wrapped in his own illusions and, it turns out, delusions about the love of his life, whom everyone, it seems, has had a go with, including Benny, a London bus driver (Stephen K Amos) who is in the play’s only settled relationship with the dull but loyal Bernie (Alan Turkington). Elyot has a masterstroke amidst these splendidly realised mature gay men to contrast them with the idealism of an emerging younger gay man Eric, who works in the local bar and also as a painter and decorator, whom we first meet as he is repainting Guy’s flat. As played by the smooth-skinned James Bradwell, he is a touching combination of naivety and knowing grit.

Lee Newby’s set — pitched at an off-centre angle in the tiny Turbine — becomes a fully-inhabited home for a play that is like a more reserved version of the American classic The Boys in the Band, updated for an even bigger existential threat to their existence than internalised homophobia.

Like Mart Crowley’s script for that play, Elyot’s play bristles with great one-liners underneath its tragic undercurrent; but it’s still odd that it won both the Evening Standard and Olivier Awards for 1994 and 1995 respectively for Best Comedy.

Watching the production, I laughed for sure; but I cried, too.