In a feature for The Stage earlier in the week, Jessica Korvavos, president of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Really Useful Group, was asked to sum up the last year:

“A year when singing and dancing in public have been against the law? It’s been like a horrible dystopian cross between Footloose and Groundhog Day.”That was an appropriately musical response.”

It has certainly been a vision of a dystopian future that suddenly arrived in the here and now. We’ve all been forced to adapt to it, like it or not. And we’ve each of us had to make our own kind of peace with it. Or not.

As opera composer Nico Muhly told the New York Times in a similar article asking artists in different genres to comment on what the year had meant for them, said:

“Obsessing over what it did to me specifically almost inexcusably leaves out my constant awareness of the damage to my community, the arts in general, to say nothing of the half a million dead Americans. This whole thing is Very Bad.”

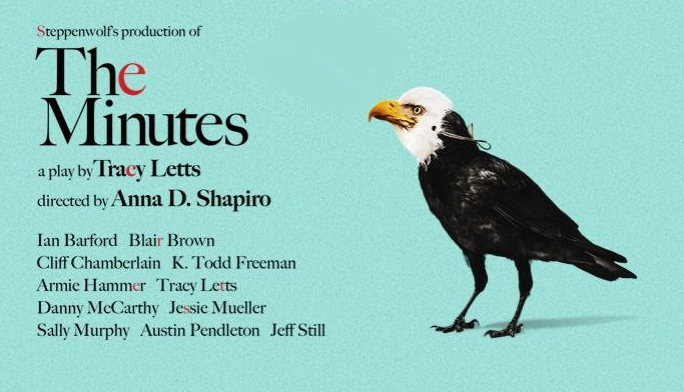

In the same feature, artists were asked what they’d managed to accomplish during the year of lockdown. Tracy Letts, playwright and actor, answered very poignantly and personally:

“I’ve made nothing. On four separate occasions, I arranged my schedule with [my wife] Carrie so I could have six uninterrupted hours a day to write. All four times, I emerged from my office after two or three weeks, rattled, defeated, feeling lousy about myself. My wife finally said, ‘Here’s what you have to do: read books, watch movies, cook dinner and take care of our boy.’ That is what I’ve done. And while my family is my focus and my joy, from a creative standpoint, this year for me has been a dust storm. I’m normally involved in a number of creative endeavours, in different forms, but the theatre is my lifeblood and I don’t know who I am without it. The plug getting pulled on [the Broadway transfer of] The Minutes was truly devastating for me.

I feel like a heel even saying that since so many people in this country and around the world are suffering as a result of this pandemic in ways I can’t even fathom. But it’s the simple truth. I can’t do the computer theater, it’s too depressing for me, and I’ve turned down a couple of on-camera jobs because I am just as scared of this virus as I was a year ago. Creatively, I’m lost.”

But it was not all bad. Asked for his memories of the year, Muhly replied:

“I had been having an awful, soul-crushing day of artistic torpor, and was ‘celebrating’ by buying socks in the abandoned Uniqlo on 34th street when they called the election for Biden. The staff and I were all screaming and dancing around. I walked up to Times Square, which was initially deserted and then filled up as if in a time-lapse video. Within five minutes, the whole of New York was there: a man on a Segway with a three-legged corgi, the Naked Cowboy, some gay people turned up in Daisy Dukes with ‘Kamala’ glitter-gunned onto the bottoms. A man had a jeroboam of champagne and started pouring it into plastic cups. I think it was the first time I’d been genuinely, three-dimensionally happy in months.”

And musician Phoebe Briegers spoke for many — including myself — when she said:

“I’ve read a lot of studies saying that it’s going to be hard to have memories of this year, because it all just feels like the same day. When you do different things, they stand out in your memory and that’s how you remember things. A lot of it feels like the same day. There are some standout moments, though. I remember when John Prine died [in April], that was the deepest, darkest part of Covid. But there were definitely some highs, like getting to play S.N.L., and just seeing my band again.”

That’s exactly what I’ve missed most. Both defining my days (or nights) by the different things I’ve seen in theatre, and the sense of community: the kind I join when I sit in a room full of (mostly) strangers watching a play or musical.

As former New York Times critic Charles Isherwood put it in a piece for Broadway News,

“I have always been quite shy, but I didn’t realise until it instantly evaporated how much pleasure I took in the sheer act of theatregoing: for me, theatre could provide the comfort of community without the ordeal of actually having to talk to people. (The actors do that for you, God bless them.) I never thought I would miss the brisk professionalism of Broadway ushers, the scramble for the bathroom at intermission, wading through the scrum people to enter a Broadway house, or my knees grinding into the back of the seat in front of me. I even look forward to the day when, sitting in a crowd in the dark, I hear the noxious chiming of a cellphone — such sweet music!

Who would have thought?”

In the Washington Post, columnist Catherine Rampell concurred:

“I missed the diversion of live theatre, of course — the opportunity to escape into worlds whose characters faced misfortunes and joys altogether different from those around me. I missed the ability to exalt in the virtuosity of members of my species: the trill of a silver soprano, a brilliant plot twist, a jubilant fan-kick. And I missed having a different lens through which to view questions of class and race and family, enemies and friends, compassion and conflict. Theatre can entertain and energise, sure, but at its best it has left me deeply, squirmingly uncomfortable. Great shows have a way of dislodging calcified beliefs and behaviour, as only storytelling can.

Those things I missed almost immediately. What it has taken me a year to realise is how much I also miss the community of the audience — the strangers surrounding me, obscured by the dark, who have tacitly agreed to escape and exalt and squirm together.”

And yet the crisis that has kept people apart has also brought others together. As Nick Allott, former Managing Director of Cameron Mackintosh Ltd who transitioned to non-executive chairman during the last year, told Alistair Smith, editor of The Stage, in a feature,

“The sector is probably more united than we’ve ever been before, but we’re united in adversity. What we’ve got to do is remain united when the good times come back. Next time the fire alarm goes off, we need to make sure we’re all lined up wearing the same uniforms and able to respond in the same way. Instead of everyone asking: ‘Have you seen the axe? Where’s the tap and the bucket?’, which is what happened. We know all of that, but what we can’t afford to do – when this is all over – is let that drift apart again.”

That’s a great analogy. But will the good times actually come back? In the New York Times, various creatives were asked what they want to achieve before things return to normal. Novelist Ali Smith replied,

“I think normal’s gone. If I chance to be lucky enough to pass safely from here to something that can be called a new normality, I want to be ready for the different place we’ll be in, I want to be up to the challenge and the change.”

Playwight and screenwriter Katori Hall (whose play The Mountaintop transferred all the way from London’s Theatre503 to Broadway, and won the Olivier for best play along the way, and also responsible for the book to Tina: the Tina Turner Musical) said:

“I don’t think things will return to normal. I’m more interested in establishing new habits to move into the new normal. I also should just finish my novel.”

And composer Nico Muhly also concurred:

“I don’t think there is a return to normal in the performing arts, I’m sorry to say. We have to make a new normal, and build a lot of it from scratch. This period has shone light on an unbelievable amount of baked-in inequality and rotten practices rooted in the foundation of everything we do.”

That much is certainly true. And if any good comes out of what has happened, it will be that it has forced a reckoning with those inequalities.

Many have set out bold new agendas for changes they’d like to see. In The Stage, Lyn Gardner has suggested:

“Theatre will come back, and much as I long for it to do so, I don’t want it to come back the same as it was, because it has always been about a few winners and an awful lot of losers who simply don’t get the opportunities, or who drop out before they can prise open the doors.

We don’t want to come back stronger than ever – we need to come back kinder, with a far bigger and broader welcome, without all the barriers kept in place because secretly they suit us, and we need to take more care of our most precious resource: artists.”

Also in The Stage, BAC’s artistic director Tarek Iskander has set out a challenge to funders, venues and large companies, and freelancers to create a more inclusive future. “While grieving over all the misery and damage this pandemic has wrought on our sector, this remains a unique opportunity to reshape the performing arts.” In other words, it is an opportunity and invitation to bigger changes across the arts.

According to a news feature in The Guardian on Thursday, “British theatre needs to be ‘completely rebuilt’ in the wake of Covid-19 to make it more accessible to people from diverse backgrounds.”

Reporting on Blackstage UK, an initiative founded by actor Gabrielle Brooks [see first episode below], to respond to structural racism in the arts, she is quoted saying: “Yes, we have the devastating effects that the pandemic has had on the arts financially, but we will survive [and] what we have been given here is a gift to completely rebuild. I mean completely start anew from scratch.”

As ever, this includes seeking to drive changes towards making audiences themselves more diverse. Brooks tells The Guardian, “I’ve stood on the stage and I thought to myself: ‘Wow, there is no one looking back at me that reflects me.’ Not only does it make me feel lonely, but it also makes me makes me feel like there’s no progression.”

In The Stage, Manchester Home executive director Jon Gilchrist suggests that change will inevitably come out of this period:

“The pandemic has exposed the already widening divisions in parts of our society. A year of very limited activity means we can’t simply think we’re ‘picking up where we left off’, the context that we operate in has changed. In Manchester, we’ve been doing a lot of work with the Manchester Health and Care Commissioning Board. There is a belief that the arts are fundamental to the recovery of our towns, cities and communities, and undoubtedly have a positive impact on the life and health outcomes of our residents. Also, our understanding of the possibilities of digital has accelerated. We have found new ways of reaching audiences that might have taken years if not through necessity. I think the critical factor now will be balancing these new innovations with the need to bring audiences (safely) back into venues to experience work together.”

Also in Manchester, Royal Exchange executive director and joint chief executive Stephen Freeman comments in the same feature,

“Our world has changed and as an industry it is important that we ask ourselves: ‘Who has a voice in strategic decisions?’ and be ready to give way to change.”

Matthew Xia, artistic director of Actors Touring Theatre, fears that it may not actually happen:

“I want the hashtags to be policy: #CultureNeedsDiversity #NothingAboutUsWithoutUs #WeShallNotBeRemoved. I think time has been the most incredible benefit, allowing for reflection on change. However, once we’re moving at speed once more, I fear the reflections will be forgotten.”

Two last, and more hopeful, thoughts. The first comes from Amanda Gorman, the young poet who was featured in Biden’s presidential inauguration, who told the New York Times:

“I think if I could go back in time and give myself a message, it would be to reiterate that my value as an artist doesn’t come from how much I create. I think that mind-set is yoked to capitalism. Being an artist is about how and why you touch people’s lives, even if it’s one person. Even if that’s yourself, in the process of art-making.”

I’ve taken this lesson to heart myself. My value as a critic doesn’t come from how many people I reach. Even if it’s one person, that’s enough. And that may indeed be myself, in the act of writing itself.

And second: from a delightful conversation between actors Anne-Marie Duff and Cush Jumbo, who met working on the National’s production of Common in 2017, published in The Guardian recently, on what returning to theatres is likely to be like:

AMD: Being in a room when a dancer holds another dancer or an actor makes themselves vulnerable is going to be so potent. We’ve been behind masks for ages. It’s very powerful psychologically what that does to us – you can’t see me smile, can’t hear me properly. It will be amazing to hear someone play a guitar in front of you. The real world is what we do, but the arts are who we are.

CJ: There’ll be orgasms in the aisles!