Yesterday, the resumption of theatre life began in New York; meanwhile, tomorrow is the 50th anniversary of the Broadway opening night of Stephen Sondheim’s Follies, his jagged and shattering tribute to the musicals as well as the marriages of yesteryear, as James Goldman’s characters confront their current predicaments as middle and old-aged people looking back on their lives through the prism of the nostalgia of their theatrical pasts — all set to a score that gently pastiches the songs of the period while actually improving on them.

That these two events are now interlinked in the present, as Broadway continues to face the biggest-ever crisis of its existence that has had it shut down for more than a year now (and with no firm dates for its return, even now), is a poignant reminder of the illusions and delusions, and the alternate dreams and lies, that variously come to define and disappoint us, in life as well as the theatre.

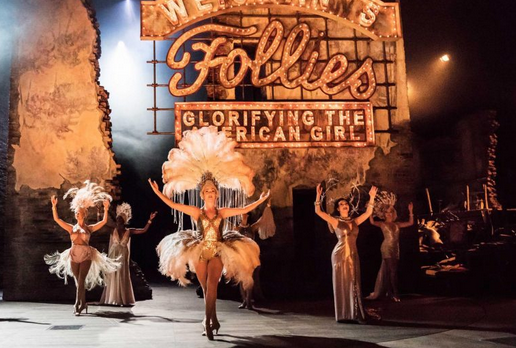

Follies is set at a final reunion of the performers who used to perform at the Weismann Theatre (an impresario modelled on Ziegfeld), before their theatre is torn down — as many legendary ones were in the sixties, seventies and even into the eighties — in the name of progress, or at any rate high-rise hotels and car parks.

Famously inspired by a photograph of the great film actress Gloria Swanson standing amidst the ruins of a Manhattan movie palace that was in the process of being demolished, it is a brutal and bitter portrait of life’s terrible compromises and missed opportunities, distilled in an impressionistic parade of performances that weave out of the past into the present, as its characters confront who they have become as they look back on who they once were.

And after 50 years, it is a show that has accompanied many of us through our own lives and losses. It’s one of those shows that theatre fans can never forget their first experience of.

It played a significant role in the lives of the last three chief critics of the New York Times. An undergraduate Frank Rich — probably the most influential theatre critic of the second half of the last century — it was his undergraduate review of the show for the Harvard Crimson, when the show was playing its original pre-Broadway run at Boston’s Colonial Theatre that marked out his future as the stunningly perceptive critic he would become.

As he wrote,

These are old women coming down the staircase. They are dumpy, their hair is dyed, they don’t exactly keep time with the music. They are not very secure, and, for that matter, neither is the staircase they are descending. It is ratty. But it doesn’t make any difference. The staircase is on the stage of a theatre that is about to become a parking lot, and the women-well, the women don’t have much farther to go before they die.

….The action of this show takes place during one evening, the night a group of Follies girls are reunited for a party thirty years after their theatre closed its doors. The occasion is the demolition of their building itself, although the glamorous home of their show has already in fact been gutted by the ravages of age. Age has not improved these women’s lives either, and Follies is largely the many little stories its characters have to tell.

It is a measure of this show’s brilliance (and its brilliance is often mind-hoggling) that it uses a modern musical form, rather than the old-fashioned one that the Follies helped create, to get at its concerns.”

His review ends with this devastating insight:

“Follies is a musical about the death of the musical and everything musicals represented for the people who saw and enjoyed them when such entertainment flourished in this country. If nothing else, Follies will make clear to you exactly why such a strange kind of theatre was such an important part of the American consciousness for so long. In the playbill for this show, the setting is described as “a party on the stage of this theatre tonight.” They are not kidding, and there is no getting around the fact that a large part of the chilling fascination of Follies is that its creators’ are in essence presenting their own funeral.”

It presents, in other words, a last hurrah not just for this particular theatre on this particular night, but the possible end of musicals themselves. What a verdict!

In a piece in the New York Times earlier this week, Jesse Green — the current chief critic of the paper — quotes this review and says of Rich’s observation that it is a musical about the death of the musical that this is “a wonderful paradox but one that undermines the experience. If musicals are dead … is this one too?” But he is more hopeful: “It may be about the death of musicals, but Follies pointed the way to bringing them back to life.”

He also points out its achievements:

“Not only is Follies, which opened on Broadway on April 4, 1971, still here 50 years later, trailing a string of revivals, revisals and gala concerts, but it is also now recognized as the high-water mark of the serious “concept” musical, that genre in which form and function are brought into the tightest possible alignment…..

In its seriousness and cleverness, in its matching of style to substance, in its use of a medium to comment on itself, it has hardly ever been bettered. In any case, ambitious musical theatre would never be the same; we would not have Fun Home or Hamilton or Dear Evan Hansen without Follies hovering behind them, the most beautiful ghost of all.”

And each of us carries the ghosts of previous productions we’ve seen of the show each time we see it — and more importantly, where we were in our lives when we saw each of them.

Ben Brantley, who was joint chief critic with Jesse Green before retiring from regular reviewing last year (during which time he wrote about seven incarnations of the show), first saw it when he was 16, on his very first trip to New York from his hometown in North Carolina, with his parents.

As he wrote this week,

“At long last, I was exactly where I had yearned to be for most of my young life. I had arrived in the holy land, which for me was a show palace in New York City, the world capital of my childhood fantasies. My very first Broadway musical, a form of entertainment I regarded as a religion, was about to begin.

Then the lights went down in the cavernous Winter Garden Theatre. It got dark, which I had expected. It stayed dark, which I hadn’t. The stage was flooded in shadow, and you had to squint to make out the people on it. Some were tall, spectral beauties from another era in glittering headdresses, and others were as ordinary as my parents, dressed up for a night out. None of them looked happy.

The grand orchestral music seemed to be eroding as I listened, like some magnificent sand castle dissolving in the tide, as sweet notes slid into sourness. This was definitely not Hello, Dolly! or Bye Bye Birdie or Funny Girl, whose sunny, exclamation-pointed melodies I knew by heart from the original cast recordings.

I didn’t know what had hit me. I certainly didn’t know that it would keep hitting me, in sharp and unexpected fragments of recollection, for the next 50 years.”

My own first encounter with Follies was, of course, not in a theatre but via its original cast album, some of whose songs I’d first heard even before that on another cast album, namely for the 70s revue of his work Side by Side by Sondheim that was one of producer Cameron Mackintosh’s first hits, in which Julia McKenzie, Millicent Martin and David Kernan performed such songs from its core as Ah, Paree!, Buddy’s Blues, Broadway Baby, Losing My Mind and I’m Still Here, and a cut number, Can That Boy Foxtrot.

VIDEO: Julia McKenzie sings a definitive version of ‘Broadway Baby’ on the 1983 Royal Variety Show:

By the time Follies received its London premiere in 1987 at the Shaftesbury Theatre — produced by Cameron Mackintosh and again starring McKenzie (she played Sally Durant Plummer, opposite Diana Rigg’s Phyllis Stone) –I was working in my first post-University job at Dewynters, where I was responsible for editing souvenir brochures and theatre programmes for West End shows.

So I couldn’t have been more excited to be playing a tiny part in that show’s West End premiere, which was also the first time I was seeing it. But of course I was only 25 at the time, and I couldn’t possibly appreciate the depth of feeling it arouses for those of us, double that age or more, when we see it at the ages the characters in the show itself now are.

As I wrote in my review for LondonTheatre.co.uk of the show’s 2017 revival at the National Theatre,

Thirty years on from the original West End version of Follies that premiered at the Shaftesbury Theatre in 1987 – and 46 years on from its Broadway premiere at the Winter Garden in 1971 – there are even more layers and ghosts in play. It’s a show about roads not taken and wrong choices made that evocatively lives in the present of the reunion it is set at. Director Dominic Cooke and choreographer Deamer happily make many good decisions on the roads they choose to play this journey on, bringing haunting echoes of the past into play along with the close-up emotions of the present.

In a column for The Stage, I also wrote about revisiting that production twice in the same week (I ended up seeing it five times in all during that run, and then twice more when it returned in 2019; that still didn’t equal the 15 or 16 times I saw the 1987 version), and said:

It was a unique experience each time.

Partly it’s about who you share it with – but also where you sit. The Tuesday revisit was with one of my oldest friends, now a television executive with whom I’d also seen the original London production in 1987. The 30 years between then and now is precisely the same 30 years that separate the characters in the show; watching this tale of fractured friendships and relationships accompanied by someone with whom my own relationship has endured gave the show a strange extra punch.

Two days later, I attended the show again, when the show was being performed for NT Live, and I wrote:

It’s such a rich and painful show about adult disappointment; all the more resonant as I get older. It might very well be unbearable soon!

After the show I ran into Gemma Bodinetz, artistic director of Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse, and we exchanged notes. But, rather hilariously, it turns out we were completely at cross purposes. She’d just seen Network, not Follies. It wasn’t until later that she realised and tweeted me: “Even when you were talking about when you first saw it 30 years ago I was nodding thinking you meant the film. And of course they are both about midlife crisis. Interesting how long we agreed without realising we were talking about two different brilliant shows.”

Great art is always in conversation both with itself and with other great art, and nothing illustrates this more keenly.

Meanwhile, for the last 12 months and counting, our conversations have mostly been around the absence of theatre, as Broadway has been shutdown for all of them and the West End for most of them.

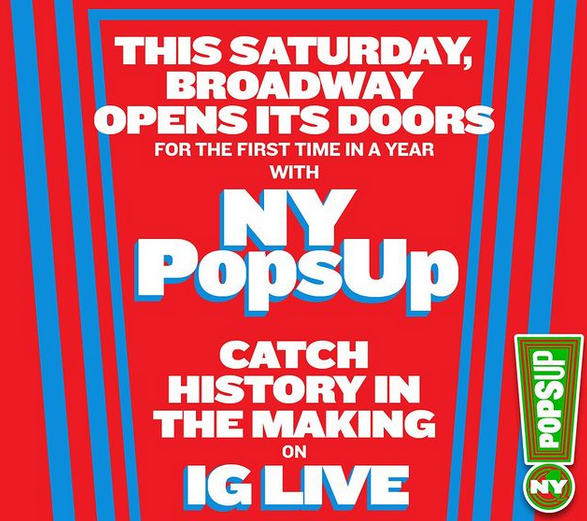

With the West End tentatively planning another return on May 17 (subject to final government approval, to socially distanced audiences, after another five months hiatus since it previously staged a short-lived comeback in November), yesterday saw a tiny window opening in New York, too, with performing arts establishments allowed by New York state governor Andrew Cuomo to host audiences at 33 percent capacity, with a limit of 100 people indoors or 200 people outdoors.

Those very low numbers mean that Broadway is mostly not included: as the New York Times reported the night before,

“As that date has drawn closer, it became clear that the arts scene will not be springing back to life, but inching toward it. It isn’t just Broadway theatres and large concert halls that see the one-third capacity rule as prohibitive; it’s smaller venues, including some of the city’s foremost jazz and rock clubs, as well.”

There is, however, a one-off performance today in a Broadway theatre, with a special performance for frontline workers, that will be available to watch on Instagram Live at 1pm EST — 6pm in London

.

At Off-Broadway’s Kraine Theatre on the Bowery on the Lower East Side, monologuist Mike Daisey is performing to 22-person audience, in a venue that usually seats 99, but will also reach a bigger crowd via being live streamed. According to the New York Times,

“All 22 audience members must be at least two weeks past their final dose of a vaccine. Daisey, who hasn’t performed for a live audience since December 2019, said that this requirement was the only way he would put on his act indoors at this stage of the pandemic.”

At least it’s a start, I suppose.