Gay and feminist theatre, once confined to the fringe, has long been joyfully embraced by the mainstream — the National, who originally gave the British premiere of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America after it was born at San Francisco’s Magic Theatre in the 90s, subsequently revived it (and took that revival to Broadway); ditto the Young Vic’s production of Matthew Lopez’s The Inheritance, that transferred both to the West End and on to Broadway.

In the same way, plays like Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls and Pam Gems’s Piaf have long ago become modern classics, with repeated revivals (the latter is due to re-open Nottingham Playhouse this July, then play a season at Leeds Playhouse later this year).

It’s likewise been heartening to see black theatre artists and playwrights, once centred around race-specific companies like Talawa and Eclipse or bold programming at places like Stratford East and the former Tricycle (now the Kiln), occupying other important spaces from the National (as demonstrated last year by Death of England: Delroy) down.

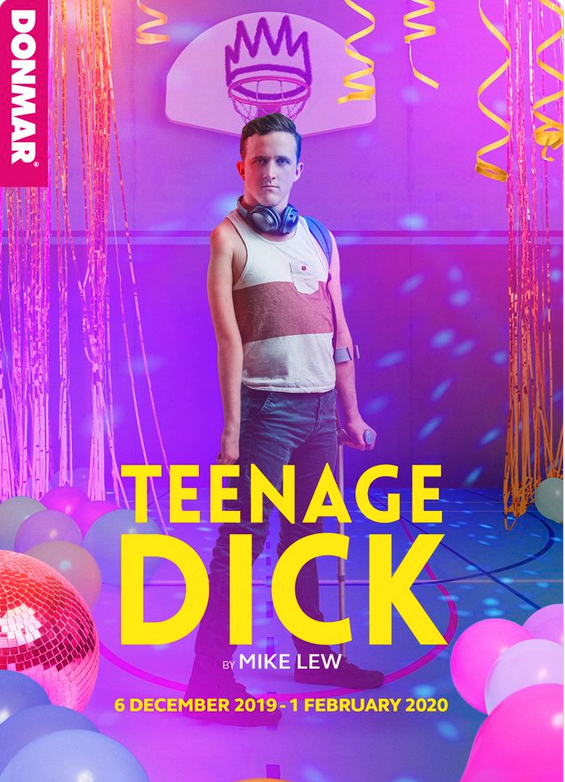

It’s peculiar, in this regard, that disabled arts and artists are yet to make a substantial cross-over, at least in British theatre. Yes, there was one happy incidence of this at the Donmar Warehouse, when gay disabled actor Daniel Monks starred in their production of Teenage Dick in 2019.

As I put it in my review for LondonTheatre.co.uk at the time:

In October, the Trafalgar Studios hosted a West End revival of the late Peter Nicols’s play 1967 play A Day in the Death of Joe Egg that revolves around a married couple caring for their severely disabled daughter. The production broke new ground by the casting of Storme Toolis, who herself has cerebral palsy, in the title role. As I wrote in my review: “It puts the disability at the centre of the play in plain sight, and we can’t look away. Nor, watching this finely-tuned production, would we want to.”

And affirming that theatre is no longer just a question of what stories get told but who gets to tell them now is the London premiere of Teenage Dick, which premiered last year at New York’s Public Theatre, in which playwright Mike Lew specifies in the published script, “Cast disabled actors for Richard and Buck. They exist and they’re out there… In no case should able-bodied actors ‘play’ disabled.”

In the New York production, the title character was originated by an actor who, like the one in the recent production of Joe Egg, has cerebral palsy. In London, he is being played now by a young London-based Australian actor called Daniel Monks who has hemiplegia. And it matters, not just because of the question of opportunities being newly afforded to disabled actors, but also because the play is about outsider status and classroom bullying which become amplified when the stakes are palpably increased.”

These were, of course, both plays which featured disabled actors playing disabled characters.

But the even bigger revolution afoot is when disabled actors are cast for roles where disability is not described as part of the person’s characteristics, but they bring themselves to those roles to expand the language of the production.

The most thrilling version of this I’ve yet seen was when the wheelchair-bound Ali Stroker played the role of Ado Annie in a production of Oklahoma! at Broadway’s Circle in the Square in 2019.

That year she became the first person who uses a wheelchair to win a Tony Award (for Best featured actress in a musical, pictured above); in her acceptance speech, she said: “This award is for every kid who is watching tonight who has a disability, who has a limitation or a challenge, who has been waiting to see themselves represented in this arena — you are.”

She lost the use of her legs after sustaining a spinal cord injury in a car accident when she was 2 years old, leaving her paralysed from the chest down; but when she was seven, she discovered a passion for singing, when she appeared in the title role of a production of Annie in the back yard of her New Jersey home. And since then, she’s never looked back, only forwards.

On Sunday night she was guest on Seth Rudetsky’s invaluable weekly The Seth Concert series (pictured above) of live online concerts with Broadway theatre personalities, and this was one of the very best I’ve yet seen. She has a naturally engaging warmth and honesty, and she’s not afraid of confronting the elephant in the room of her own disability.

Sure, as with colour-blind casting, the point is to integrate those attributes into the character, not apologise for them; as she told the New York Times in 2019, speaking about that childhood role as Annie Warbucks,

“When I got on stage, it was the first time that I felt powerful. I was used to people staring at me, but they were staring at me because I was in a wheelchair. And when I was on stage, they were staring at me because I was the star.”

Theatre liberated her — and she’s INVITING people to look at her now.

“So many times, our society is taught, ‘Don’t look, don’t stare and don’t ask — that would be rude’. As an artist, I’m saying, ‘Look at me now. Look at my body. Look how I move my chair.’ I’m asking, and that makes me feel my most powerful self.”

And she brought those qualities to the role she was playing too. Talking about Ado Annie, she says,

“She doesn’t ever apologize for who she is. She doesn’t have any shame about who she is. Her wants, her desires, are so clear. And her desire to explore, through sexuality and relationship, feels so true for me. Her line — ‘How can I be what I ain’t?’ — so many girls need to hear that. So many people need to hear that.”

She shone a radiant new light on the character, through the unique prism of her own experiences that brought her here. The New York Times also asked her if she gets tired or resentful of answering questions around these issues. Her answer is warm and embracing:

“I know in many ways that this is what I was born to do. When a little baby is injured, you always wonder why. And I think for my parents it’s so clear I was meant to be in this seat, to bring my joy, and my light, and my love, to something that a lot of our culture and a lot of our society looks at as just a shame, or a tragedy. I don’t think any part of my life is not meant to be.”

On Seth Rudetsky’s concert, not only was her stunning talent as a vocalist on vivid display, so was her humanity.

As I tweeted while watching her:

She’s a symbol for an inclusivity of ALL talent on Broadway. She spoke about some of the challenges — both physical (in the sense that many old Broadway theatres are just not disability-friendly in their backstage areas) and with people’s expectations. She found it hard when she started out getting auditions, especially on roles that weren’t calling specifically for disabled actors; it takes a leap of imagination from a creative team to think she could be included. Her wheelchair itself, she finds, is being auditioned, as well as she is.

She also spoke about using a manual one rather than an electric one, as it has afforded her greater freedom to move around New York City; it can simply be folded and put into the back of a cab, rather than require special provisions like an electric one might.

She is doing her own work to make herself accessible; now the world needs to catch up. She’s a true inspiration and a stunning talent.