On Saturday evening I returned to the theatre for the first time in over five months — the longest period I’ve ever spent without attending a live performance since I first discovered theatre more than four decades ago, at the age of just 14. I’ve actually been in a kind of mourning and grief at the loss of this essential part of both my professional and personal life; but I’ve also been forced into a dejected acceptance. There just wasn’t an alternative.

On Saturday evening I returned to the theatre for the first time in over five months — the longest period I’ve ever spent without attending a live performance since I first discovered theatre more than four decades ago, at the age of just 14. I’ve actually been in a kind of mourning and grief at the loss of this essential part of both my professional and personal life; but I’ve also been forced into a dejected acceptance. There just wasn’t an alternative.

But once the government announced their phased return to allowing performances to resume in outdoor settings — with socially distanced audiences — I was elated to see the Open Air Theatre, Regent’s Park announce plans to revive their 2016 production of Jesus Christ Superstar in a re-staged concert version: a production I’d loved so much that year that I saw it twice more (on tickets I bought to see it), and then again each time they brought it back in 2017 and then indoors to the Barbican Theatre in 2019 (reviewing the latter for Londontheatre here.)

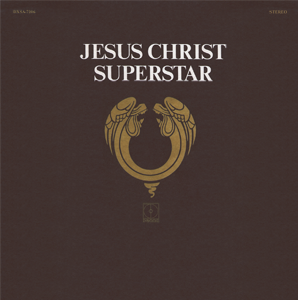

I’ve loved this score since I was a teenager and first heard (and got to know every single of Tim Rice’s lyrics by heart) on the  original concept album that was released in 1970 (pictured right), ahead of the show’s theatrical premiere. That occurred on Broadway in 1971 (the only Andrew Lloyd Webber scored musical to debut there ahead of the West End, until School of Rock in 2015), with a different West End production premiering a year later at the Palace Theatre. I was living in South Africa, where I was born, at the time — and the album was illicitly brought into the country (as the ruling apartheid-era government had banned it, sight unseen or songs unheard, on the grounds that it was blasphemous to treat Jesus so irreverently). Ahead of emigrating to Britain in 1979, my parents brought my brother and I to London on a holiday visit in 1973, and perched in the Palace’s upper circle, Jesus Christ Superstar also became the very first West End show I ever saw, aged 11.

original concept album that was released in 1970 (pictured right), ahead of the show’s theatrical premiere. That occurred on Broadway in 1971 (the only Andrew Lloyd Webber scored musical to debut there ahead of the West End, until School of Rock in 2015), with a different West End production premiering a year later at the Palace Theatre. I was living in South Africa, where I was born, at the time — and the album was illicitly brought into the country (as the ruling apartheid-era government had banned it, sight unseen or songs unheard, on the grounds that it was blasphemous to treat Jesus so irreverently). Ahead of emigrating to Britain in 1979, my parents brought my brother and I to London on a holiday visit in 1973, and perched in the Palace’s upper circle, Jesus Christ Superstar also became the very first West End show I ever saw, aged 11.

I’ve followed Lloyd Webber’s career closely ever since — and Jesus Christ Superstar remains, for me, his finest musical achievement — though his greatest theatrical one is a toss up for me between Evita and The Phantom of the Opera. I became obsessed by Michael Grandage’s 2006 West End revival of Evita, starring the firebrand Elena Roger in the title role of Eva Peron, and during the last few weeks of its run at the Adelphi, I went once every week. I remember meeting Philip Quast, who played Peron in that production (pictured right, with Roger), in Adelaide, Australia, a few weeks after the run ended, and he told me that word had reached the company that I had become so smitten. That was also, coincidentally, the start of what has become one of my greatest theatrical friendships; I’ve since visited his home in Sydney, stayed with him when he was on tour in Mary Poppins in Melbourne, and joined his 60th birthday celebration in Britain when he was in the midst of rehearsing for Follies.

I remember meeting Philip Quast, who played Peron in that production (pictured right, with Roger), in Adelaide, Australia, a few weeks after the run ended, and he told me that word had reached the company that I had become so smitten. That was also, coincidentally, the start of what has become one of my greatest theatrical friendships; I’ve since visited his home in Sydney, stayed with him when he was on tour in Mary Poppins in Melbourne, and joined his 60th birthday celebration in Britain when he was in the midst of rehearsing for Follies.

Just like Evita, Jesus Christ Superstar also has a deep personal resonance for me; as I know it does for so many people. And this year, of course, is the 50th anniversary of the album’s first release, too, so it’s a particularly powerful moment, after so many barren theatre-free months, that it’s also the first “West End” (or at least SOLT registered) show to return.

But as much as I was looking forward to seeing it again, there was suddenly an unexpected roadblock: when I checked in about the availability of tickets with the theatre’s appointed freelance publicists, I was told they were unable to oblige, thanks to the financial challenges posed by the dramatically reduced capacity of the auditorium (a loss of nearly 900 tickets), and also the cancellation costs of the first part of the season.

In a press statement at the time the show was announced, the theatre’s executive director William Village wrote, “Following the government’s announcement last week that outdoor theatres may re-open, we have been working around the clock to find a way to open in August and September this year. With social distancing, seating capacity has been dramatically reduced to 390 seats (down from 1,256). This makes producing any large-scale show economically extremely challenging, particularly as we are an unfunded organisation. Nevertheless, both for us as a venue, and the industry as a whole, we believe it is incumbent upon us to do everything possible to re-open this year, and we’re delighted to announce this special concert staging of our award-winning production of Jesus Christ Superstar.”

Instead, critics were invited to buy tickets (at £65 each), if they wanted to cover it. This put me, and some of my colleagues, in an impossible situation; many publications won’t cover the cost of the ticket, either, so some critics have been forced to swallow the cost themselves. Given that I’ve not earned a penny in the last five months, that is a burden too much. So I resigned myself to not being able to see it after all.

Of course, given that I saw their three previous runs multiple times, it could be said that I’d seen it already; but I was also very keen to see this version, as I know it has been substantially re-staged. And of course, I’ve been grieving the loss of live theatre — for someone who used to go to the theatre between five and twelve times a week (yes, really!), these last five months have been brutal.

So the personal sense of grief I’d been experiencing during this extended and unprecedented time was compounded by this fresh loss. And when I read some of the reviews that appeared last Thursday, I actually wept at the loss. I mentioned my sadness on twitter. One friend — an actor and playwright — responded by asking me why I wasn’t going. When I told him, he very kindly replied offering to take me as his guest, since he’d bought four tickets for himself and his two teenager kids and had a spare.

So I did, after all, get to see it; but as my friend’s guest, not the theatre’s. Which is why this isn’t a review. And actually, it feels right, too: I didn’t, in the end, want to see it wearing my critical hat, only my joyful hat of being in a theatre again.

And it’s a show that lends itself ideally to a concert version, anyway; as a through-sung rock oratorio, it’s more rock concert than fully-fledged musical.

But also, as wonderful as it was to be there, it was both sad and disheartening, too: live theatre is really not sustainable under these conditions. The theatre is losing 2/3rds of its revenue; and all of it, if there’s another lockdown and the theatre is forced to shut down again.

I remain a passionate fan of the theatre before I’m a critic; and I really want it not just to survive but thrive again. Opening in this tentative way is obviously an attempt to make the best of a terrible situation — but it has left me feeling more concerned about how viable it will be if the current rules stay in place, not less. As Mary Magdalene sings in the show, “Can we start again, please?”, I wanted to ask the same question. But this isn’t, alas, a true re-start; it’s for an extremely limited audience and run. So, to paraphrase another song in the score, Everything’s not quite alright, at least not yet.