It’s a fact of life that most actors forge and learn their craft in the theatre. Some may be lucky enough to achieve fame and fortune via screen work, but the original debt is to the theatre where they began.

I was reminded of this essential fact repeatedly in the last few days. This weekend a filmed version of David Bowie’s final collaboration Lazarus has been made available by digital screenings around the world; he attended the premiere at New York Theatre Workshop in December 2015, shortly before dying exactly five years ago today, even as that show was still running and where I first saw it myself after his passing. Ivo van Hove’s production was filmed in London when it transferred here in 2017, with Michael C Hall reprising his New York performance as Thomas Jerome Newton — the humanoid alien who comes to Earth from a distant planet to find water, whom David Bowie himself played in Nicholas Roeg’s 1976 film The Man Who Fell to Earth, and whose story the show continues, interpolating Bowie classics with a few newly-penned tracks.

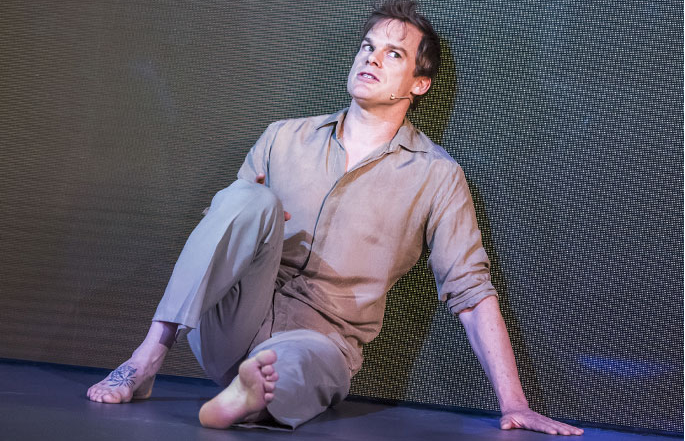

I interviewed Hall (pictured above as Newton) at the time for The Stage, and as I wrote then, the year we marked the 20th anniversary of his completing his graduate school training in acting at New York’s Tisch School of the Arts. He has spent most of those two decades in the lead roles of a pair of big television shows: Six Feet Under and Dexter.

As he told me, “I never anticipated that I would spend 13 consecutive years playing two different television characters – five years on Six Feet Under, then eight years on Dexter. But that’s how it went, and I was able to dip my foot into the theatre from time to time during the course of that run. And shortly after Dexter ended, I returned to Broadway in Will Eno’s play The Realistic Joneses. That just reinvigorated my love for being on stage, and I’ve been primarily focused on that since.”

After Tisch, he began the usual actor’s round of working with Off-Broadway companies, including the Public, Manhattan Theatre Club and the original workshops for Sondheim’s Wise Guys (which later morphed into Road Show), at New York Theatre Workshop. He would go on to take over on Broadway in the leads of Cabaret and Chicago, as well as Hedwig and the Angry Inch. So Lazarus was a rare instance of him originating a leading role in a musical, made all the more daunting for working with Bowie himself. As he told me, “The first time I sang these songs for anyone but myself was when I went to the apartment of Henry Hey, the musical director. We spent about an hour singing them through. Then David came over, and there were just the three of us, with me singing the songs with David in the room listening.”

Theatre, unlike his TV work, is a living beast, and he also spoke about the pleasure of bringing it to London, after previously playing the same role in New York. “The experience of being up there is quite familiar. The sensibility of the audiences, though, is perhaps different, their sense of humour, their sense of ownership over Bowie, the sense that this is a homecoming for him and his work and that final chapter of his creative output.”

Bowie, who coincidentally once played Broadway himself — taking over the title role in the original New York production of Bernard Pomerance’s The Elephant Man in 1980 — was always a man ahead of his time, and in a thoughtful review for WhatsOnStage, Sarah Crompton noted, “Watching it again, I am struck more than ever by the way the show parallels confinement and escape, despair and hope, and in the end leaps for the better options. Newton escapes when he finds humanity and unselfish love. It seems entirely fitting that Bowie, a man who was never afraid to try something new, left as his last legacy a project that doesn’t absolutely work but which speaks even more strongly now than it did when he made it, and asks us to find our better angels as we search for a way forwards.”

And that’s more true now than ever. In Friday’s Daily Mail, Baz Bamigboye reported on a new Julian Fellowes scripted TV series, The Gilded Age, which stars Christine Baranski and Cynthia Nixon — two actors I first saw on the New York stage, long before they’d acquire TV fame for The Good Fight and Sex in the City respectively. (I’ll never forget Baranski in an otherwise eminently forgettable murder mystery musical called Nick and Nora — re-dubbed Nick and Snora by theatre wags — that ran for just a week in 1991, after some 71 previews, in which she sang about her character’s vocal talents called ‘Everybody Wants to do a Musical’ — “My high C may sometimes shriek, I think I hit in twice last week”. (Though YouTube doesn’t preserve her version, my great friend Alison Jiear once sang an inimitable version of it below).

As Baz also reported, “The show has been a boon, too, to Broadway names who, like theatrical colleagues over here, have seen their livelihoods eroded. The line-up includes Denee Benton, Kelli O’Hara, Donna Murphy, Debra Monk, Katie Finneran and Simon Jones.

Also recently announced — and another boon for actors whose careers all began in the theatre — is the cast for the 5th season of The Crown. Two of my very favourite actors are on board: Imelda Staunton and Lesley Manville, as the Queen and her sister Margaret. Also announced is Jonathan Pryce as Prince Philip and Elizabeth Debicki as Princess Diana, an Australian actor who has appeared in London in the premiere of David Hare’s The Red Barn at the National in 2016, and I’d also previously seen reprising her performance in Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Genet’s The Maids when it transferred to New York in 2014, playing the mistress opposite the title characters taken by Cate Blanchett and Isabelle Huppert — two more marvellous screen stars who also faithfully return to the stage with some regularity (pictured below).

Blanchett even co-ran Sydney Theatre Company with her writer/director husband Andrew Upton for five years, from 2008 to 2013; she was last seen on the London stage in When We Have Sufficiently Tortured Each Other at the National in 2019; at the first night I was seated next to Upton, and could not bring myself to look at him by the end of what I would go on to call “a tedious waste of time” in my one-star review for londontheatre.co.uk at the time.

But I revere Blanchett, both as an actor and a person: in 2017, I had the privilege of interviewing her — with Upton and the then new artistic director of Sydney Theatre Company, in New York. And as I wrote for The Stage, again, “It is the 10am on the morning after the Broadway premiere of the 2016 Sydney Theatre Company production of The Present (pictured above), a modern adaptation of Chekhov’s Platonov, written by Andrew Upton and starring his wife Cate Blanchett, when they sweep into a bookshop-cum-coffee shop in midtown Manhattan on Lexington Avenue to meet me. Blanchett has already been pictured that morning walking her son to school; and after we meet, a car collect her to take her off for a day’s filming on Ocean’s Eight, a spin-off of the Ocean’s Trilogy due for release this summer.”

Blanchett was herself a big part of the company’s own international reach. As she told me that day, “International touring became a big thing for us. We were so proud of what was happening at Sydney Theatre Company that we wanted to get it out, and one of the most obvious ways was for me to be a part of that. So I ended up touring quite a lot.” The Maids that I saw in New York was part of that.

The best actors, in other words, regularly commit themselves to the thrill (and sometimes the chills) of being challenged by working in the most merciless medium around: the live theatre, which provides no place to hide.

The aforementioned Staunton (who turned 65 yesterday) and Manville (who is a year younger) both epitomise this commitment, and have gone on from long stage careers to Oscar-nominated film performances (Staunton for Vera Drake in 2005, Manville for Phantom Thread in 2018). What I’ve also always loved about both of them is that neither brook any lazy journalistic nonsense.

As Alexandra Pollard wrote in an interview in The Independent with Manville in May 2019, “Read any of the articles written about Lesley Manville [pictured] lately and they’ll tell you the actor is having a moment. “What they’ve been saying is that I’m having a ‘late-flowering career’. Their words, not mine. I felt that it was always flowering.” And she also punctures another actor’s myth in the same interview: Pollard remarks being surprised about an improvised food fight between her character and Daniel Day-Lewis that appears in the DVD outtake, and she replies, “Well there you go. I think that sums up what the myth is and what the reality is. I mean yes, that myth does prevail, and he is very in character, but once you’re in character, you can kind of go anywhere and it’s OK.”

Also interviewed by Pollard, and again in The Independent in 2019, Imelda Staunton is equally forthright. It opens with this paragraph:

Not for the last time today, Imelda Staunton is telling me off. We’re discussing her role in ITV’s new six-part, real-life drama A Confession, in which she plays the mother of Becky Godden-Edwards, who was murdered in 2003. It’s distressing to watch, I say. “Well yes, of course it is,” she replies. “It’s about two bloody dead daughters.”

She also reveals her practical, no-nonsense approach to the supposed glamour of attending the Oscars and being besieged by hundreds of paparazzi on the red carpet.

“It’s stupid,” says Staunton. “They go, ‘IMELDA!’ They ask all those poor girls who are in those dresses, ‘Right turn around, turn around, look back, look back.’ You want to go, ‘Just take the picture.’” There’s a limit to her sympathy, though. “For women now, I think, ‘Stop wearing those dresses, girls.’ I don’t know what the pressure is on serious actresses to wear those clothes. Come on ladies, we’re trying to move it on, so maybe don’t wear that figure-hugging thing. But then, they want to be able to say that’s what they want to wear. It is tricky. That’s one night of your life. It’s fine as long as you don’t believe it.”

The secret to Manville and Staunton’s brilliance is that neither believe it. As Staunton tells it, too:

“I avoid the showbiz glare. I like to just get on with my life. After work, I don’t want to then have to dress up and be with people talking about the job I do. No, I just do the job and then I go home and do my shopping and my cooking. There’s no doubt that that other side of the business has increased a million-fold. It’s all just noise and fluff and filler. The word celebrity makes me feel sick when it’s applied to me, because I’m not. I’m a jobbing actor. That’s really all I want to do, and I don’t know what all that other stuff’s about.”