I got back yesterday morning from a week in New York, more about but was too busy both there and since getting back to post my usual weekly update till now! The trip was squeezed in-between my weekly teaching commitments at ArtsEd — I left for Heathrow direct from Chiswick, viagra approved which is where ArtsEd is handily located for such quick escapes, decease after an afternoon teaching last Monday, and then returned yesterday in time to head direct to the school from the airport again to teach again yesterday afternoon!

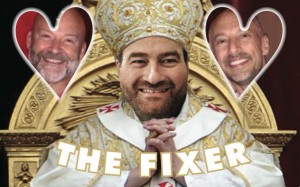

And on Sunday, of course, I also ran close to the wire, since that was the reason I was in New York last week in the first place — to officiate at the wedding of my friends Dana P Rowe and Andrew Scharf (pictured either side of me in artwork created by Thomas Mann), that took place that morning; but we had to fly home that night from New York so had to leave the reception by 3.30pm to get home, get our bags, and head to JFK by subway for an 8pm flight!

And on Sunday, of course, I also ran close to the wire, since that was the reason I was in New York last week in the first place — to officiate at the wedding of my friends Dana P Rowe and Andrew Scharf (pictured either side of me in artwork created by Thomas Mann), that took place that morning; but we had to fly home that night from New York so had to leave the reception by 3.30pm to get home, get our bags, and head to JFK by subway for an 8pm flight!

Still, we obviously made it. And I can’t say what a profound honour it was to be invited to officiate at a wedding in this way. Dana, a musical theatre composer who I first met back in 1997 when he came to London for pre-production meetings for his show The Fix that was being premiered at the Donmar Warehouse in a production that was directed by Sam Mendes and co-produced with Cameron Mackintosh, has been a friend for 18 years now. As Sondheim’s lyrics for I’m Still Here have it, “Good times and bum times, I’ve seen them all/ And, my dear, I’m still here/ Plush velvet sometimes/ Sometimes just pretzels and beer, but I’m here.” Change the ‘I’m’ to ‘we’re’, and that’s Dana and me.

I calculate that I’ve been in five major relationships during that time, including (for the last seven years, my husband Mark), and Dana has been in three, including the man who became his husband on Sunday, Andrew Scharf. It took both of us a long time to find our own soul-mates in love, but we’ve been soul-mates in friendship for a long time.

I couldn’t have been happier when Dana P (as I always call him!) met Andrew four years ago. He’d just had some extremely bum times, and Mark and I had holidayed earlier that summer with Dana, on his own, in Provincetown. The following summer, Mark and I got married — and Dana brought Andrew to the event, before all four of us went on a group holiday to P-town as part of our honeymoon, and did so again the year after in 2014. It was on that trip that they excitedly shared some news with us: sitting on a little bench on Commercial Street, near the Purple Feather ice cream and chocolate parlour, Andrew had proposed — and Dana had accepted!

Fast forward to Sunday, and — after getting ordained through the Universal Life Church a few months ago, and subsequently making a group trip to City Hall to get me officially registered as an officiant — I was able to marry them to each other. I quoted John Dempsey’s lyrics to The Witches of Eastwick that Dana P wrote the music for in which the three title characters share their romantic aspirations: “Make him mine, make him mine/ Make him handsome as the devil/ yet perfectly divine. /Make him mine./The ultimate companion,/ The ideal design/ All manner of man in one man/ Make him mine.” And on Sunday, I told the gathered throng of family (including Dana’s adult son and daughter, and his two grandchildren by his daughter) and friends, “Today these handsome devils who are both perfectly divine are going to fulfil that as they become the other’s ultimate companion: all manner of man in one man for each other. (The grooms are pictured above with Dana P’s son Landon behind him and me behind Andrew).

Fast forward to Sunday, and — after getting ordained through the Universal Life Church a few months ago, and subsequently making a group trip to City Hall to get me officially registered as an officiant — I was able to marry them to each other. I quoted John Dempsey’s lyrics to The Witches of Eastwick that Dana P wrote the music for in which the three title characters share their romantic aspirations: “Make him mine, make him mine/ Make him handsome as the devil/ yet perfectly divine. /Make him mine./The ultimate companion,/ The ideal design/ All manner of man in one man/ Make him mine.” And on Sunday, I told the gathered throng of family (including Dana’s adult son and daughter, and his two grandchildren by his daughter) and friends, “Today these handsome devils who are both perfectly divine are going to fulfil that as they become the other’s ultimate companion: all manner of man in one man for each other. (The grooms are pictured above with Dana P’s son Landon behind him and me behind Andrew).

It feels anti-climactic in the circumstances to talk about the various shows I shoe-horned into my visit, though I wouldn’t be a theatre addict if I hadn’t crammed them in — and I did, seven of them! Five were Broadway shows — three of which I’d seen before, the Tony winning Fun Home, the Tony missing Something Rotten (apart from one for featured actor Christian Borle), and Les Miserables to catch Alfie Boe joining the show). The other two off-Broadway, including Daddy Long Legs that’s now at the Davenport Theatre on W45th Street and I’d previously seen when it played a season at London’s St James.

But these were just diversions, not the main event. And another thing to look forward to when I got back was ArtsEd itself, where I’d persuaded my friend Scott Alan — who laid on that fantastic birthday party for me last month that I wrote about here — to come and share his experiences as a New York songwriter with them. Many of my students (pictured left with Scott on the front row, and me in the back row) are huge fans — one told me at the end of the class what an idol he was to him, and Scott duly filmed a video message for his sister!

But these were just diversions, not the main event. And another thing to look forward to when I got back was ArtsEd itself, where I’d persuaded my friend Scott Alan — who laid on that fantastic birthday party for me last month that I wrote about here — to come and share his experiences as a New York songwriter with them. Many of my students (pictured left with Scott on the front row, and me in the back row) are huge fans — one told me at the end of the class what an idol he was to him, and Scott duly filmed a video message for his sister!

Across less than a seven day period over last week, case I’ve been in New York (from where I returned a week on a week ago Monday), England, Wales and Scotland — so all I missed out was Northern Ireland, but otherwise I’ve covered the old countries and one of the Colonies, as well!??I’ve already covered my New York travels in my diary of a theatre addict here last week, and in the week I returned I saw (a relatively) modest six shows, but I’ve stretched my own usual geographical boundaries by going to one of them in Wales and another in Scotland, as well as four in London, at venues both high profile and not, including the Donmar and West End on the one hand, and the tiny Hope Theatre and much smarter St James (though there’s not much smarter to choose between them in the (dis)comfort stakes).

What took me to Wales was yet another production of Sweeney Todd — my third this year, so far, though one of them I actually saw twice over, so it was really my fourth! Sweeney Todd is becoming the Hamlet of musical theatre in terms of the number of times we can expect to see it in a single year — though it’s more akin to Macbeth in the bloody stakes. Welsh National Opera’s version that I saw the opening of in Cardiff (David Arnsperger and Janis Kelly, who star as Sweeney Todd and Mrs Lovett are pictured above; my review is here) is itself a re-visit of a production I’ve also seen before: first done at Dundee Rep in 2010 (where I didn’t see it but it earned mouth-watering reviews) by director James Brining when he in charge there, then at West Yorkshire Playhouse (when Brining took that theatre over in 2013), and where I caught it first. it has now been re-cast with a mostly operatic cast, and an interesting change of perspective occurred.

What took me to Wales was yet another production of Sweeney Todd — my third this year, so far, though one of them I actually saw twice over, so it was really my fourth! Sweeney Todd is becoming the Hamlet of musical theatre in terms of the number of times we can expect to see it in a single year — though it’s more akin to Macbeth in the bloody stakes. Welsh National Opera’s version that I saw the opening of in Cardiff (David Arnsperger and Janis Kelly, who star as Sweeney Todd and Mrs Lovett are pictured above; my review is here) is itself a re-visit of a production I’ve also seen before: first done at Dundee Rep in 2010 (where I didn’t see it but it earned mouth-watering reviews) by director James Brining when he in charge there, then at West Yorkshire Playhouse (when Brining took that theatre over in 2013), and where I caught it first. it has now been re-cast with a mostly operatic cast, and an interesting change of perspective occurred.

Firstly, I realised that Brining’s high-concept staging — setting it within a mental asylum and playing it out in giant metal containers — wouldn’t seem so odd in an opera house, where they’re used to such scenic liberties being taken. And secondly, in an opera world where sound is more important than dramatic verisimilitude, the fact that the title role was played by David Arnsperger, a clearly Germanic sounding singer, didn’t matter, either: he sang beautifully, even if his Cockney was closer to Hamburg than Hackney. But it was also nice to see how easily a couple of musical theatre performers slipped in among them, including the wonderful Jamie Muscato as Anthony Hope and George Ure as Toby (I nearly wrote Boq).

What took me to Scotland was more personal, and outside of my usual comfort zone — not to mention that of the person I’d gone to see there. It was to see a piece, originally made by choreographer Javier de Frutos for Ballet Rambert, being revived by Scottish Ballet called Elsa Canasta, which is a dance drama set to songs by Cole Porter that are sung live by a singer. In the original, it was Melanie Marshall; now it was the turn of Nick Holder (pictured left with the company), who has become a very good friend and someone I credit with turning my life around in the last year for reasons unrelated to the theatre.

What took me to Scotland was more personal, and outside of my usual comfort zone — not to mention that of the person I’d gone to see there. It was to see a piece, originally made by choreographer Javier de Frutos for Ballet Rambert, being revived by Scottish Ballet called Elsa Canasta, which is a dance drama set to songs by Cole Porter that are sung live by a singer. In the original, it was Melanie Marshall; now it was the turn of Nick Holder (pictured left with the company), who has become a very good friend and someone I credit with turning my life around in the last year for reasons unrelated to the theatre.

But Holder is also a thrilling performer; I’ve loved him for years, but I’ve only really gotten to know him since he appeared in a brilliant production of Assassins at the Union (directed by Michael Strassen), and we became Twitter friends, then friends away from Twitter, too. He was outstanding in Rufus Norris’s production of the landmark London Road at the National (and its subsequent film version), and also in Norris’s Everyman; he’s going to be in The Threepenny Opera there next. From the Union to the National and now Scottish Ballet, he is always an original — and the figure you are drawn to instinctively on any stage. Here, delivering knock-out renditions of Cole Porter songs with a burning intensity and anguish, full of lungs and longing, he broke my heart once again.

![]() I had a personal connection to another show that started my week: 46 Beacon at the Hope Theatre was a delicate two-hander by my long-time friend Bill Rosenfield, who I first got to know in his native New York, but who relocated to London over a decade ago and now lives not too far from the Hope in Islington. In fact, his play ended up at the Hope after I took him to see a show there (Snoo Wilson’s Lovelong of the Electric Bear) earlier this year, and introduced him to the artistic director Matthew Parker, so that puts me in another direct connection to it. So, after making that full disclosure, I can also say that I was really moved by this beautiful exploration of awakening sexuality and the casual dismissals we make of each other as we use each other’s bodies for pleasure and discard them so quickly and casually afterwards. I’ve done this so many times in my life, and you don’t always realise the consequences. This play made me think of the investments that the other person might make, especially when they’re a lot younger.

I had a personal connection to another show that started my week: 46 Beacon at the Hope Theatre was a delicate two-hander by my long-time friend Bill Rosenfield, who I first got to know in his native New York, but who relocated to London over a decade ago and now lives not too far from the Hope in Islington. In fact, his play ended up at the Hope after I took him to see a show there (Snoo Wilson’s Lovelong of the Electric Bear) earlier this year, and introduced him to the artistic director Matthew Parker, so that puts me in another direct connection to it. So, after making that full disclosure, I can also say that I was really moved by this beautiful exploration of awakening sexuality and the casual dismissals we make of each other as we use each other’s bodies for pleasure and discard them so quickly and casually afterwards. I’ve done this so many times in my life, and you don’t always realise the consequences. This play made me think of the investments that the other person might make, especially when they’re a lot younger.

In a review of Christopher Shinn’s Teddy Ferrara, another play about contemporary gay lives that opened at the Donmar Warehouse last week, Michael Coveney said of the play: “The ironic point is that it’s still hard to be gay and happy even as society bends over backwards, so to speak, to accommodate diversity, difference and even promiscuous life-style.”

The ‘even’ gave me pause — that sounds very much like a specific judgement against exactly what society was accommodating — as did the cheap line about bending over backwards, which is also a very reductive (and reactionary) view of gay sexuality, which doesn’t necessarily (but often very pleasurably) involves bum-fun. Sometimes it is difficult to unpack the baggage behind what a writer is trying to say, and I mean Coveney as much as Shinn; last night Coveney shouted at me in the street on the way to In the Heights for the “outrageous” accusation of homophobia I’d made here, which I’m happy to withdraw, though his words still stand in all their loaded meaning.

I had my own difficulties unpacking Shinn’s play, which I reviewed here, for very different reasons. As I wrote, “The play seeks to have an all-purpose inclusivity as it portrays [its characters] exclusivity from each other, and the casual and not-so-casual slights, hurt and damage they variously inflict on each other.” It duly becomes diffuse and overburdened with lots of subplots.

The week also took me to the slightly unimaginative, but very well sung, Pure Imagination — a traditional jukebox show devoted to the work of the prolific lyricist Leslie Bricusse, whose title song of course is also currently to be heard in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory at the West End’s Drury Lane. The six-man band (led by Michael England) and five-strong cast are pure class, including the always-wonderful Julie Atherton, whose version of the Superman theme song ‘Can you Read My Mind?’, (lyrics by Bricusse to John Williams’s melody) equalled the original gloriously sung by Maureen McGovern, and was worth the price of admission alone. I also enjoyed seeing and especially hearing Niall Sheehy (pictured above), a new face and voice to me, give full power minus the usual cheese factor to ‘This is the Moment’ from Jekyll and Hyde (Bricusse lyrics to Frank Wildhorn’s tune).

The week also took me to the slightly unimaginative, but very well sung, Pure Imagination — a traditional jukebox show devoted to the work of the prolific lyricist Leslie Bricusse, whose title song of course is also currently to be heard in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory at the West End’s Drury Lane. The six-man band (led by Michael England) and five-strong cast are pure class, including the always-wonderful Julie Atherton, whose version of the Superman theme song ‘Can you Read My Mind?’, (lyrics by Bricusse to John Williams’s melody) equalled the original gloriously sung by Maureen McGovern, and was worth the price of admission alone. I also enjoyed seeing and especially hearing Niall Sheehy (pictured above), a new face and voice to me, give full power minus the usual cheese factor to ‘This is the Moment’ from Jekyll and Hyde (Bricusse lyrics to Frank Wildhorn’s tune).

Finally, I made yet another return visit to Gypsy — and why not? Last week it was also filmed for posterity, so I’ll be able to re-visit it many, many more times in the years to come, but Imelda Staunton (pictured left) is truly phenomenal. It’s difficult to describe just how transcendent Staunton is; she gives it such heart (and heartache), resilience and power; and keeps it always truthful.

Finally, I made yet another return visit to Gypsy — and why not? Last week it was also filmed for posterity, so I’ll be able to re-visit it many, many more times in the years to come, but Imelda Staunton (pictured left) is truly phenomenal. It’s difficult to describe just how transcendent Staunton is; she gives it such heart (and heartache), resilience and power; and keeps it always truthful.

But the thrill of Jonathan Kent’s old-fashioned but pitch-perfect production is that it isn’t a one-woman show but a true ensemble effort, right through the ranks. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a better Herbie than Peter Davison, a better Tulsa than Dan Burton, or a performance of such timid brilliance than Lara Pulver’s Louise. And the trio of principal strippers are a vanity-free riot in the show’s scene-stealing ‘You Gotta Get a Gimmick’. The show is, in every other regard, completely gimmick-free; just the real deal.