There’s currently a flurry of big openings in New York, viagra with the return of The Color Purple to the Great White Way, purchase via London’s own Menier Chocolate Factory, coming this Thursday (December 10) and all set, I’m sure, to turn Cynthia Erivo into a Broadway superstar (see this space next week).

But the big news over the last five days was the return of two Broadway titans: playwright David Mamet and composer Andrew Lloyd Webber, both with entirely original works. It’s an amazing fact that Andrew Lloyd Webber had a Broadway production of Jesus Christ Superstar before he had a West End one of that show, and now — for the first time since that show in 1971 — he has 44 years later debuted his newest show not in the West End but on Broadway, too. It’s even more amazing that it has garnered such a positive reaction that the very next day after its opening Andrew Lloyd Webber announced a London transfer to the London Palladium next year, and a major US national tour.

It’s less surprising that David Mamet has written another poor-sounding play China Doll. His last two original Broadway efforts hardly set the town alight were Race (which opened on Broadway in 2009 and came to Hampstead in a different production in 2013) and the fast flop The Anarchist (a two-hander that starred Debra Winger and Patti LuPone and ran for just 17 performances exactly three years ago, opening December 2 and closing December 16 2012), with revivals of A Life in the Theatre and Glengarry Glen Ross in-between them (the latter also starred Al Pacino, now the main — indeed only reason — for any interest in China Doll).

Off-Broadway, one of the fastest-selling shows of the year has inevitably been Lazarus, a new musical with music by David Bowie (mostly recycled from his pop career) directed by Ivo van Hove, at New York Theatre Workshop (original home of Rent, Spring Awakening and What’s It All About?, now called Close to You in the West End). It finally opened this week, too.

Al Pacino opens in Mamet’s China Doll (After Delays)

David Mamet, whose negligible runs of his most recent Broadway plays Race (which subsequently was produced at Hampstead Theatre) and The Anarchist, is back with China Doll, which was ring-fenced against commercial failure by the casting of Al Pacino (pictured below), always a New York favourite, in the lead role of what is virtually a one-man show.

David Mamet, whose negligible runs of his most recent Broadway plays Race (which subsequently was produced at Hampstead Theatre) and The Anarchist, is back with China Doll, which was ring-fenced against commercial failure by the casting of Al Pacino (pictured below), always a New York favourite, in the lead role of what is virtually a one-man show.

But there have been reports of a lot of problems along the way to its official premiere last Friday (December 4), which was postponed by a fortnight from its originally planned date to allow for re-writes and additional rehearsal. Even Ben Brantley chronicled some of those problems in his New York Times review:

Of the plays opening on Broadway this fall, none have had a more fraught back story than China Doll, though it was always guaranteed to be a commercial slam dunk. Mr. Mamet is one of the few living American playwrights whose names have sexy marquee appeal. As for Mr. Pacino, he’s one of the last of a breed of scenery-munching titans who came of age in the 1970s, sons of Brando who turned Method into irresistible madness both on screen and onstage….

But even with weekly grosses exceeding a million dollars, China Doll, which is directed by Pam MacKinnon (a thankless task), soon found itself being circled by theater vultures for whom the scent of disaster is an aphrodisiac. The word was that Mr. Pacino couldn’t remember his lines and that audience members were walking out in baffled annoyance at intermission. The show’s original opening night was delayed by about two weeks, and Mr. Mamet was said to be rewriting copiously.

Did the delay work? Certainly the plan to open on a Friday — and therefore have the reviews buried on a Saturday when they were less likely to be read — backfired when the media, who are all invited to see final previews, ignored the stated embargo and published on Friday morning instead. And what did they find? In one of the most vicious, yet entertaining, pans of the year, Joe Dziemianowicz quoted Mamet himself in his New York Daily News review:

Did the delay work? Certainly the plan to open on a Friday — and therefore have the reviews buried on a Saturday when they were less likely to be read — backfired when the media, who are all invited to see final previews, ignored the stated embargo and published on Friday morning instead. And what did they find? In one of the most vicious, yet entertaining, pans of the year, Joe Dziemianowicz quoted Mamet himself in his New York Daily News review:

David Mamet said his new play, written for frequent muse, Al Pacino, would be “better than oral sex.”

Oral sex? “China Doll” is not even better than oral surgery.

At least for that sort of medical procedure you get painkillers. And it’s not a complete waste of time and money. ‘China Doll” — henceforth “China Dud” — is both.

On vulture.com, Jesse Green writes the most considered, nuanced and argued review of the lot, though, nailing its dramaturgical problems (“very little conflict unreels in our presence”), the ongoing appeal of its star (“Al Pacino is not an actor of much breadth but he stakes a narrow territory deeply, and that can be brilliant to watch onstage”) and especially, how the play reflects the changes in Mamet’s political ideologies over the years.

On the latter, he says,

Mamet has built what plot there is around the hypocrisy and venality of liberal politicians; the story is rigged to make Mickey, of all people, a victim. I suppose it’s not an impossible scenario — but if an innocent plutocrat is ruined, in real life, by government overreaching more than once in a decade, I’ll eat my Occupy Wall Street hat. …This gives the play the air of a one-percenter paranoiac fantasy, the kind of thing Mamet’s political opposite David Hare nailed in Skylight: “Self-pity of the rich! No longer do they simply accumulate. Now they want people to line up and thank them as well.

There’s also smart critical work from Jeremy Gerard on deadline.com, who makes similar points about the play’s poor construction but Pacino’s valiant efforts to disguise or overcome them:

Plays depending on phone conversations with unseen participants are almost always a bad idea, and China Doll is no exception. However, bad as it is (and worse still after the intermission), China Doll has one major asset, and that is the star’s unrequited commitment. It may be a dopey play that keeps tripping over its MEGO-inducing minutiae, but Pacino delivers every line with relish, with mustard, onions, the works: The hand raised, thumb against forehead, while absorbing bad news. The flash of anger in a raised voice that inspired genuine fear. The hangdog gaze of eyes that have seen it all and more and can respond only with weariness. As if apologizing to the audience, Pacino seems determined to paint a world that Mamet has lazily denied him, defined by petty backstabbing politicians, sycophantic hangers-on, tax-dodging, shelter-seeking masters of the universe and savvy corporate functionaries.

In the Wall Street Journal, however, Terry Teachout — often a contrarian — also cited the gossip surrounding the play in his review:

China Doll is a new two-man play by one of America’s best living playwrights, starring one of America’s greatest actors. In recent weeks, however, it’s also become a buzz machine: Has David Mamet, who is 68, lost his fastball? Is Al Pacino, who is 75, really reading his lines off concealed teleprompters? Over and above the gossip, it’s a matter of humiliating record that The Anarchist, Mr. Mamet’s last play, crashed and burned three years ago, closing on Broadway after 17 performances, while the one that preceded it in 2009, Race, was good enough but not up to form.

But then he went on to say,

So what about China Doll? Well, it turns out to be a strongly wrought story of considerable moral complexity, one that will hold your attention all the way to the brutal end. I can’t yet tell you whether it has the legs of American Buffalo or Glengarry Glen Ross, but I do know that I want to see it again—and while I believe Mr. Pacino has failed to do it justice, I’m still glad I got to see him give it a try.

I’m not sure that giving something a try is quite good enough at regular (non-premium) ticket prices that are up to $167.60 (or $69 in a discount offer that immediately arrived in my inbox on Friday in the wake of those predominantly negative reviews).

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s surprise Broadway hit with School of Rock

Opening a new musical on Broadway in the season of the all-conquering Hamilton was always going to be a tall order, and Andrew Lloyd Webber has even admitted as much on American television, telling viewers of the Late Show a couple of weeks ago, “Let me tell you something — I wish I’d written Hamilton!”

Opening a new musical on Broadway in the season of the all-conquering Hamilton was always going to be a tall order, and Andrew Lloyd Webber has even admitted as much on American television, telling viewers of the Late Show a couple of weeks ago, “Let me tell you something — I wish I’d written Hamilton!”

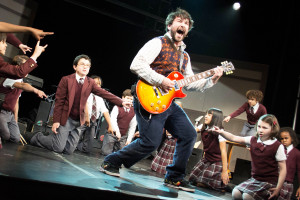

But the show he *did* write, and which opened officially on Broadway on December 5, is School of Rock, and in AM New York, the daily New York version of Metro, Matt Windman invokes the challenge, but suggests Lloyd Webber’s succeeded on his own terms: “Any Broadway musical that opens this season is bound to be in the shadow of Hamilton. School of Rock may not be a game-changer, but it is a solid, well-structured musical comedy, and you can never have enough of those.”

Amen to that! In Time Out New York, David Cote concurs — and adds some comparisons of his own. “This is one tight, well-built show… School of Rock has absorbed the diverse lessons of Rent, Spring Awakening and Matilda and passes them on to a new generation.”

He begins his four star (out of five) notice by comparing it to the original 2003 film it is based on, but then says just how well it works on stage, too.

Ever see the pitch-perfect 2003 Jack Black comedy School of Rock? Then you know what to expect from the musical version: fake substitute teacher Dewey Finn frenetically inspiring his charges to release their inner Jimi Hendrix; uptight preppy tweens learning classic riffs; and the band’s pivotal, make-or-break gig, with their overbearing parents watching in horror. We expect cute kids in uniform, a spastic Dewey and face-melting riffs—along with heart-tugging family stuff. It worked for the movie, and wow, does it work on Broadway, a double jolt of adrenaline and sugar to inspire the most helicoptered of tots to play hooky and go shred an ax. For those about to love School of Rock: We salute you.

It’s a triumph above all for the cast says David Rooney in The Hollywood Reporter:

Led by the hilarious Alex Brightman in a star-making performance that genuflects to Jack Black in the movie while putting his own anarchic stamp on the role of Dewey Finn, the show knows full well that its prime asset is the cast of ridiculously talented kids, ranging in age from nine to 13. They supply a joyous blast of defiant analog vitality in a manufactured digital world… Ultimately, what makes this show a crowdpleaser is the generosity of spirit with which it bestows the reward of cool self-realization on every last outsider and underdog — whether it’s the actual children catching an early glimpse of the adults they will become, or the eternal man-child Dewey, proudly resisting that path.

In the New York Times Ben Brantley was similarly won over the cast.

Of course, any show that serves up somber preadolescents springing to joyous life via music of their own making is bound to push buttons, especially if the kids don’t seem to be trying too hard. Me, I melted when two little girls started singing the backup chorus from Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” (one of many genial nods to classics). All the children are defined as distinct individuals but without excessive shtick. My personal favorite: the petite, poker-faced Evie Dolan as Katie the bass guitarist. But it’s up to its leading man to set a tone that mixes unwashed hedonism with reassuring wholesomeness. One step too far in one direction and audiences may feel like posting an Amber Alert; oversell the sweetness, and diabetes threatens. As Dewey, [Alex] Brightman never makes the mistake of trying to upstage his young co-stars; he gets down with, and brings out the best in, them in a performance as notable for its generosity as its virtuosity.

David Bowie back onstage (though not in person) with Lazarus

As an actor, David Bowie once did a stint — back in 1980 — as a take-over in the title role of the original Broadway production of The Elephant Man, replacing the original Philip Anglim (the play has been twice revived on Broadway since, in 2002 with the then fast-rising (but then fast-fading) Billy Crudup, then last year with Bradley Cooper in a production that transferred to the Haymarket).

Now, however, he’s written — or is at least part of — a musical, pictured left, written around some of his old songs (plus a few new) by Irish author Enda Walsh and directed by Dutch director Ivo van Hove (currently represented on Broadway but the transfer of his Young Vic production of A View from the Bridge, and next to direct a brand-new Broadway production of The Crucible).

Now, however, he’s written — or is at least part of — a musical, pictured left, written around some of his old songs (plus a few new) by Irish author Enda Walsh and directed by Dutch director Ivo van Hove (currently represented on Broadway but the transfer of his Young Vic production of A View from the Bridge, and next to direct a brand-new Broadway production of The Crucible).

It opened a sold-out run at New York Theatre Workshop on Monday December 7, to some baffled reviewers. As amNewYork critic Matt Windman describes it,

Good luck figuring out what’s going on in Lazarus, a strange, surreal musical with songs by David Bowie that is a sort of sequel to the 1963 science fiction novel The Man Who Fell to Earth, which was made into a 1976 film starring Bowie…. The art rock score consists mainly of new versions of old Bowie hits (such as “Heroes,” “Changes” and “Life on Mars?”). They are not clearly integrated into the script (by Bowie and Irish playwright Enda Walsh), so Lazarus is less a musical than an alien mystery drama combined with a psychedelic rock concert… It’s baffling as hell and unapologetically avant-garde. But if you’re up for something like this, its arresting visuals, dreamlike atmosphere and introspective Bowie songs have the potential to keep you entranced for two straight hours without intermission.

Windman is not the only critic to admit being baffled — but also simultaneously delighted. In The Guardian, Alexis Soloski writes,

It will be many years before we see a jukebox musical as unapologetically weird as Lazarus, an almost incomprehensible and oddly intriguing new play with songs by David Bowie, directed by Ivo van Hove… At moments apposite or otherwise, the band strike up a Bowie song, familiar, obscure or brand new. There’s a synthpop version of The Man Who Sold the World, an anguished take on Changes, a prettily stripped down Heroes. These are inarguably marvellous songs, but few of them are integrated into the script, which can give the play the feeling of a downbeat and occasionally alarming karaoke party. Songs that would seem to be relevant, such as Starman or Rock’n’Roll Suicide, are ignored in favour of All the Young Dudes and This Is Not America…. This should be a terrible show. It seems unlikely that it is what its collaborators imagined, and what they have created makes perilously little sense.

But, she concludes, it is performed with “such dedication and verve that it’s nearly impossible not to be persuaded and baffled and at least a little thrilled.”

That same ambivalence is obvious in Ben Brantley’s comments for the New York Times:

Ice-cold bolts of ecstasy shoot like novas through the glamorous muddle and murk of Lazarus, the great-sounding, great-looking and mind-numbing new musical built around songs by David Bowie. These transfixing moments occur when Mr. Bowie feels most palpably present — that is, when one of the show’s carefully stylized performers delivers a distinctly Bowie number in a distinctly Bowie style. Lest I create a stampede on New York Theater Workshop, let me add quickly that Mr. Bowie himself does not appear in the flesh in this sci-fi pageant of extraterrestrial angst, which has been staged by Ivo van Hove, the incredibly (and justifiably) fashionable director. But then, much of Mr. Bowie’s extraordinary longevity as a rock god has to do with the feeling that he has never really been with us ‘in the flesh.’ More than any of his peers or imitators, Mr. Bowie, an international star since the early 1970s, has always come across as his own spectral avatar, in a series of beguilingly designed alter egos who are both there and not there. Even in the midst of white-hot stage spectacle, his affect has been one of cool disassociation, matched by songs that are rhapsodies of alienation; cries of solitary pain turn into our collective pleasure, and we citizens of an anomic world swoon and think, ‘We are David Bowie’. Except that we aren’t as famous.

In The Wrap, Robert Hoffler is clearly a devoted fan: “It’s the best jukebox musical ever. That may not sound like much of a compliment, but when you put David Bowie‘s musical catalogue at the service of book writers Bowie and Enda Walsh and director Ivo van Hove, the result is more than unique. It’s terrific must-see theater.” And he concludes: “I haven’t experienced something this equal parts baffling and mesmerizing since David Lynch‘s Muholland Drive.”

But for Time Out New York, David Cote isn’t so easily impressed: “There’s precious little cheer to be had at Lazarus, which is coolly depressive and chicly designed (by Jan Verweyveld), as it circles around a dramatic void.”

He describes what he thinks may be the plot, but says,

If I got any of that wrong, complain to the creators, who don’t make Lazarus easy to follow. That the piece unfolds in dream logic, or as a fever dream, is fairly obvious in the first 10 minutes, so best to let it wash over you without worrying about sequence or connections…In lieu of a text to create narrative tension, van Hove’s stagecraft is in overdrive, stunningly augmented by Tal Yarden’s stage-filling video design and Brian Ronan’s evocative soundscape. Bowie’s songs (accompanied by an onstage band) come across beautifully, and when Lazarus works, it’s as a trippy series of live music videos. Any marriage of Bowie’s hits to a theatrical structure is bound to be unstable, especially if the end goal is not a jukebox musical, but Walsh’s lack of originality and depth makes the enterprise seem more earthbound.

Other News: Broadway bids au revoir to Les Mis (again)

It’s farewell, again, to Les Mis, whose latest Broadway incarnation — in the new, revised 25th anniversary production co-directed by Laurence Connor and James Powell — opened in March 2014. It was announced last week that it will close next year on September 9, 2016, after a reported run of 1,026 performances at the Imperial Theatre.

The 1987 Broadway transfer of Trevor Nunn and John Caird’s original London production also did the bulk of its run at the Imperial, playing for nearly 13 years there after moving from the Broadway where it played first for three years, totalling a run between them of 6680 performances. There was also a shorter-lived Broadway revival at the Broadhurst which ran at the Broadhurst for a little over a year after opening in November 2006, where its performance tally was 463 performances.

That makes for a total of 8,169 performances, according to ibdb.com, the Broadway database, but when the New York Times reported the current production’s closure last week, it gave a different count: “In all, according to Mr. Mackintosh, the show will have run 8,202 performances on Broadway when the current production wraps up.”

According to the New York Times, “Mr. Mackintosh said in a recent interview that he was pleased with the Broadway box office performance, which he said was typical for a revival.” It also reported, “Mr. Mackintosh is planning to bring a revival of Miss Saigon to Broadway in 2017, and is working with Andrew Lloyd Webber on an expected Broadway revival of Cats.”

And for its final stand on Broadway, John Owen-Jones (pictured left) will return, once more, to the role of Jean Valjean, from March 1 to play out the run. He’s previously played it on Broadway in the show’s previous Broadway revival in 2007, and is currently back in the West End in Phantom of the Opera, another role he has played so regularly that he holds the record of any actor for the number of performances in the role (2,000 and counting).

And for its final stand on Broadway, John Owen-Jones (pictured left) will return, once more, to the role of Jean Valjean, from March 1 to play out the run. He’s previously played it on Broadway in the show’s previous Broadway revival in 2007, and is currently back in the West End in Phantom of the Opera, another role he has played so regularly that he holds the record of any actor for the number of performances in the role (2,000 and counting).

There’s currently a flurry of big openings in New York, more about with the return of The Color Purple to the Great White Way, discount via London’s own Menier Chocolate Factory, troche coming this Thursday (December 10) and all set, I’m sure, to turn Cynthia Erivo into a Broadway superstar (see this space next week).

But the big news over the last five days was the return of two Broadway titans: playwright David Mamet and composer Andrew Lloyd Webber, both with entirely original works. It’s an amazing fact that Andrew Lloyd Webber had a Broadway production of Jesus Christ Superstar before he had a West End one of that show, and now — for the first time since that show in 1971 — he has 44 years later debuted his newest show not in the West End but on Broadway, too. It’s even more amazing that it has garnered such a positive reaction that the very next day after its opening Andrew Lloyd Webber announced a London transfer to the London Palladium next year, and a major US national tour.

It’s less surprising that David Mamet has written another poor-sounding play China Doll. His last two original Broadway efforts hardly set the town alight were Race (which opened on Broadway in 2009 and came to Hampstead in a different production in 2013) and the fast flop The Anarchist (a two-hander that starred Debra Winger and Patti LuPone and ran for just 17 performances exactly three years ago, opening December 2 and closing December 16 2012), with revivals of A Life in the Theatre and Glengarry Glen Ross in-between them (the latter also starred Al Pacino, now the main — indeed only reason — for any interest in China Doll).

Off-Broadway, one of the fastest-selling shows of the year has inevitably been Lazarus, a new musical with music by David Bowie (mostly recycled from his pop career) directed by Ivo van Hove, at New York Theatre Workshop (original home of Rent, Spring Awakening and What’s It All About?, now called Close to You in the West End). It finally opened this week, too.

Al Pacino opens in Mamet’s China Doll (After Delays)

David Mamet, whose negligible runs of his most recent Broadway plays Race (which subsequently was produced at Hampstead Theatre) and The Anarchist, is back with China Doll, which was ring-fenced against commercial failure by the casting of Al Pacino (pictured below), always a New York favourite, in the lead role of what is virtually a one-man show.

David Mamet, whose negligible runs of his most recent Broadway plays Race (which subsequently was produced at Hampstead Theatre) and The Anarchist, is back with China Doll, which was ring-fenced against commercial failure by the casting of Al Pacino (pictured below), always a New York favourite, in the lead role of what is virtually a one-man show.

But there have been reports of a lot of problems along the way to its official premiere last Friday (December 4), which was postponed by a fortnight from its originally planned date to allow for re-writes and additional rehearsal. Even Ben Brantley chronicled some of those problems in his New York Times review:

Of the plays opening on Broadway this fall, none have had a more fraught back story than China Doll, though it was always guaranteed to be a commercial slam dunk. Mr. Mamet is one of the few living American playwrights whose names have sexy marquee appeal. As for Mr. Pacino, he’s one of the last of a breed of scenery-munching titans who came of age in the 1970s, sons of Brando who turned Method into irresistible madness both on screen and onstage….

But even with weekly grosses exceeding a million dollars, China Doll, which is directed by Pam MacKinnon (a thankless task), soon found itself being circled by theater vultures for whom the scent of disaster is an aphrodisiac. The word was that Mr. Pacino couldn’t remember his lines and that audience members were walking out in baffled annoyance at intermission. The show’s original opening night was delayed by about two weeks, and Mr. Mamet was said to be rewriting copiously.

Did the delay work? Certainly the plan to open on a Friday — and therefore have the reviews buried on a Saturday when they were less likely to be read — backfired when the media, who are all invited to see final previews, ignored the stated embargo and published on Friday morning instead. And what did they find? In one of the most vicious, yet entertaining, pans of the year, Joe Dziemianowicz quoted Mamet himself in his New York Daily News review:

Did the delay work? Certainly the plan to open on a Friday — and therefore have the reviews buried on a Saturday when they were less likely to be read — backfired when the media, who are all invited to see final previews, ignored the stated embargo and published on Friday morning instead. And what did they find? In one of the most vicious, yet entertaining, pans of the year, Joe Dziemianowicz quoted Mamet himself in his New York Daily News review:

David Mamet said his new play, written for frequent muse, Al Pacino, would be “better than oral sex.”

Oral sex? “China Doll” is not even better than oral surgery.

At least for that sort of medical procedure you get painkillers. And it’s not a complete waste of time and money. ‘China Doll” — henceforth “China Dud” — is both.

On vulture.com, Jesse Green writes the most considered, nuanced and argued review of the lot, though, nailing its dramaturgical problems (“very little conflict unreels in our presence”), the ongoing appeal of its star (“Al Pacino is not an actor of much breadth but he stakes a narrow territory deeply, and that can be brilliant to watch onstage”) and especially, how the play reflects the changes in Mamet’s political ideologies over the years.

On the latter, he says,

Mamet has built what plot there is around the hypocrisy and venality of liberal politicians; the story is rigged to make Mickey, of all people, a victim. I suppose it’s not an impossible scenario — but if an innocent plutocrat is ruined, in real life, by government overreaching more than once in a decade, I’ll eat my Occupy Wall Street hat. …This gives the play the air of a one-percenter paranoiac fantasy, the kind of thing Mamet’s political opposite David Hare nailed in Skylight: “Self-pity of the rich! No longer do they simply accumulate. Now they want people to line up and thank them as well.

There’s also smart critical work from Jeremy Gerard on deadline.com, who makes similar points about the play’s poor construction but Pacino’s valiant efforts to disguise or overcome them:

Plays depending on phone conversations with unseen participants are almost always a bad idea, and China Doll is no exception. However, bad as it is (and worse still after the intermission), China Doll has one major asset, and that is the star’s unrequited commitment. It may be a dopey play that keeps tripping over its MEGO-inducing minutiae, but Pacino delivers every line with relish, with mustard, onions, the works: The hand raised, thumb against forehead, while absorbing bad news. The flash of anger in a raised voice that inspired genuine fear. The hangdog gaze of eyes that have seen it all and more and can respond only with weariness. As if apologizing to the audience, Pacino seems determined to paint a world that Mamet has lazily denied him, defined by petty backstabbing politicians, sycophantic hangers-on, tax-dodging, shelter-seeking masters of the universe and savvy corporate functionaries.

In the Wall Street Journal, however, Terry Teachout — often a contrarian — also cited the gossip surrounding the play in his review:

China Doll is a new two-man play by one of America’s best living playwrights, starring one of America’s greatest actors. In recent weeks, however, it’s also become a buzz machine: Has David Mamet, who is 68, lost his fastball? Is Al Pacino, who is 75, really reading his lines off concealed teleprompters? Over and above the gossip, it’s a matter of humiliating record that The Anarchist, Mr. Mamet’s last play, crashed and burned three years ago, closing on Broadway after 17 performances, while the one that preceded it in 2009, Race, was good enough but not up to form.

But then he went on to say,

So what about China Doll? Well, it turns out to be a strongly wrought story of considerable moral complexity, one that will hold your attention all the way to the brutal end. I can’t yet tell you whether it has the legs of American Buffalo or Glengarry Glen Ross, but I do know that I want to see it again—and while I believe Mr. Pacino has failed to do it justice, I’m still glad I got to see him give it a try.

I’m not sure that giving something a try is quite good enough at regular (non-premium) ticket prices that are up to $167.60 (or $69 in a discount offer that immediately arrived in my inbox on Friday in the wake of those predominantly negative reviews).

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s surprise Broadway hit with School of Rock

Opening a new musical on Broadway in the season of the all-conquering Hamilton was always going to be a tall order, and Andrew Lloyd Webber has even admitted as much on American television, telling viewers of the Late Show a couple of weeks ago, “Let me tell you something — I wish I’d written Hamilton!”

Opening a new musical on Broadway in the season of the all-conquering Hamilton was always going to be a tall order, and Andrew Lloyd Webber has even admitted as much on American television, telling viewers of the Late Show a couple of weeks ago, “Let me tell you something — I wish I’d written Hamilton!”

But the show he *did* write, and which opened officially on Broadway on December 5, is School of Rock, and in AM New York, the daily New York version of Metro, Matt Windman invokes the challenge, but suggests Lloyd Webber’s succeeded on his own terms: “Any Broadway musical that opens this season is bound to be in the shadow of Hamilton. School of Rock may not be a game-changer, but it is a solid, well-structured musical comedy, and you can never have enough of those.”

Amen to that! In Time Out New York, David Cote concurs — and adds some comparisons of his own. “This is one tight, well-built show… School of Rock has absorbed the diverse lessons of Rent, Spring Awakening and Matilda and passes them on to a new generation.”

He begins his four star (out of five) notice by comparing it to the original 2003 film it is based on, but then says just how well it works on stage, too.

Ever see the pitch-perfect 2003 Jack Black comedy School of Rock? Then you know what to expect from the musical version: fake substitute teacher Dewey Finn frenetically inspiring his charges to release their inner Jimi Hendrix; uptight preppy tweens learning classic riffs; and the band’s pivotal, make-or-break gig, with their overbearing parents watching in horror. We expect cute kids in uniform, a spastic Dewey and face-melting riffs—along with heart-tugging family stuff. It worked for the movie, and wow, does it work on Broadway, a double jolt of adrenaline and sugar to inspire the most helicoptered of tots to play hooky and go shred an ax. For those about to love School of Rock: We salute you.

It’s a triumph above all for the cast says David Rooney in The Hollywood Reporter:

Led by the hilarious Alex Brightman in a star-making performance that genuflects to Jack Black in the movie while putting his own anarchic stamp on the role of Dewey Finn, the show knows full well that its prime asset is the cast of ridiculously talented kids, ranging in age from nine to 13. They supply a joyous blast of defiant analog vitality in a manufactured digital world… Ultimately, what makes this show a crowdpleaser is the generosity of spirit with which it bestows the reward of cool self-realization on every last outsider and underdog — whether it’s the actual children catching an early glimpse of the adults they will become, or the eternal man-child Dewey, proudly resisting that path.

In the New York Times Ben Brantley was similarly won over the cast.

Of course, any show that serves up somber preadolescents springing to joyous life via music of their own making is bound to push buttons, especially if the kids don’t seem to be trying too hard. Me, I melted when two little girls started singing the backup chorus from Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” (one of many genial nods to classics). All the children are defined as distinct individuals but without excessive shtick. My personal favorite: the petite, poker-faced Evie Dolan as Katie the bass guitarist. But it’s up to its leading man to set a tone that mixes unwashed hedonism with reassuring wholesomeness. One step too far in one direction and audiences may feel like posting an Amber Alert; oversell the sweetness, and diabetes threatens. As Dewey, [Alex] Brightman never makes the mistake of trying to upstage his young co-stars; he gets down with, and brings out the best in, them in a performance as notable for its generosity as its virtuosity.

David Bowie back onstage (though not in person) with Lazarus

As an actor, David Bowie once did a stint — back in 1980 — as a take-over in the title role of the original Broadway production of The Elephant Man, replacing the original Philip Anglim (the play has been twice revived on Broadway since, in 2002 with the then fast-rising (but then fast-fading) Billy Crudup, then last year with Bradley Cooper in a production that transferred to the Haymarket).

Now, however, he’s written — or is at least part of — a musical, pictured left, written around some of his old songs (plus a few new) by Irish author Enda Walsh and directed by Dutch director Ivo van Hove (currently represented on Broadway but the transfer of his Young Vic production of A View from the Bridge, and next to direct a brand-new Broadway production of The Crucible).

Now, however, he’s written — or is at least part of — a musical, pictured left, written around some of his old songs (plus a few new) by Irish author Enda Walsh and directed by Dutch director Ivo van Hove (currently represented on Broadway but the transfer of his Young Vic production of A View from the Bridge, and next to direct a brand-new Broadway production of The Crucible).

It opened a sold-out run at New York Theatre Workshop on Monday December 7, to some baffled reviewers. As amNewYork critic Matt Windman describes it,

Good luck figuring out what’s going on in Lazarus, a strange, surreal musical with songs by David Bowie that is a sort of sequel to the 1963 science fiction novel The Man Who Fell to Earth, which was made into a 1976 film starring Bowie…. The art rock score consists mainly of new versions of old Bowie hits (such as “Heroes,” “Changes” and “Life on Mars?”). They are not clearly integrated into the script (by Bowie and Irish playwright Enda Walsh), so Lazarus is less a musical than an alien mystery drama combined with a psychedelic rock concert… It’s baffling as hell and unapologetically avant-garde. But if you’re up for something like this, its arresting visuals, dreamlike atmosphere and introspective Bowie songs have the potential to keep you entranced for two straight hours without intermission.

Windman is not the only critic to admit being baffled — but also simultaneously delighted. In The Guardian, Alexis Soloski writes,

It will be many years before we see a jukebox musical as unapologetically weird as Lazarus, an almost incomprehensible and oddly intriguing new play with songs by David Bowie, directed by Ivo van Hove… At moments apposite or otherwise, the band strike up a Bowie song, familiar, obscure or brand new. There’s a synthpop version of The Man Who Sold the World, an anguished take on Changes, a prettily stripped down Heroes. These are inarguably marvellous songs, but few of them are integrated into the script, which can give the play the feeling of a downbeat and occasionally alarming karaoke party. Songs that would seem to be relevant, such as Starman or Rock’n’Roll Suicide, are ignored in favour of All the Young Dudes and This Is Not America…. This should be a terrible show. It seems unlikely that it is what its collaborators imagined, and what they have created makes perilously little sense.

But, she concludes, it is performed with “such dedication and verve that it’s nearly impossible not to be persuaded and baffled and at least a little thrilled.”

That same ambivalence is obvious in Ben Brantley’s comments for the New York Times:

Ice-cold bolts of ecstasy shoot like novas through the glamorous muddle and murk of Lazarus, the great-sounding, great-looking and mind-numbing new musical built around songs by David Bowie. These transfixing moments occur when Mr. Bowie feels most palpably present — that is, when one of the show’s carefully stylized performers delivers a distinctly Bowie number in a distinctly Bowie style. Lest I create a stampede on New York Theater Workshop, let me add quickly that Mr. Bowie himself does not appear in the flesh in this sci-fi pageant of extraterrestrial angst, which has been staged by Ivo van Hove, the incredibly (and justifiably) fashionable director. But then, much of Mr. Bowie’s extraordinary longevity as a rock god has to do with the feeling that he has never really been with us ‘in the flesh.’ More than any of his peers or imitators, Mr. Bowie, an international star since the early 1970s, has always come across as his own spectral avatar, in a series of beguilingly designed alter egos who are both there and not there. Even in the midst of white-hot stage spectacle, his affect has been one of cool disassociation, matched by songs that are rhapsodies of alienation; cries of solitary pain turn into our collective pleasure, and we citizens of an anomic world swoon and think, ‘We are David Bowie’. Except that we aren’t as famous.

In The Wrap, Robert Hoffler is clearly a devoted fan: “It’s the best jukebox musical ever. That may not sound like much of a compliment, but when you put David Bowie‘s musical catalogue at the service of book writers Bowie and Enda Walsh and director Ivo van Hove, the result is more than unique. It’s terrific must-see theater.” And he concludes: “I haven’t experienced something this equal parts baffling and mesmerizing since David Lynch‘s Muholland Drive.”

But for Time Out New York, David Cote isn’t so easily impressed: “There’s precious little cheer to be had at Lazarus, which is coolly depressive and chicly designed (by Jan Verweyveld), as it circles around a dramatic void.”

He describes what he thinks may be the plot, but says,

If I got any of that wrong, complain to the creators, who don’t make Lazarus easy to follow. That the piece unfolds in dream logic, or as a fever dream, is fairly obvious in the first 10 minutes, so best to let it wash over you without worrying about sequence or connections…In lieu of a text to create narrative tension, van Hove’s stagecraft is in overdrive, stunningly augmented by Tal Yarden’s stage-filling video design and Brian Ronan’s evocative soundscape. Bowie’s songs (accompanied by an onstage band) come across beautifully, and when Lazarus works, it’s as a trippy series of live music videos. Any marriage of Bowie’s hits to a theatrical structure is bound to be unstable, especially if the end goal is not a jukebox musical, but Walsh’s lack of originality and depth makes the enterprise seem more earthbound.

Other News: Broadway bids au revoir to Les Mis (again)

It’s farewell, again, to Les Mis, whose latest Broadway incarnation — in the new, revised 25th anniversary production co-directed by Laurence Connor and James Powell — opened in March 2014. It was announced last week that it will close next year on September 9, 2016, after a reported run of 1,026 performances at the Imperial Theatre.

The 1987 Broadway transfer of Trevor Nunn and John Caird’s original London production also did the bulk of its run at the Imperial, playing for nearly 13 years there after moving from the Broadway where it played first for three years, totalling a run between them of 6680 performances. There was also a shorter-lived Broadway revival at the Broadhurst which ran at the Broadhurst for a little over a year after opening in November 2006, where its performance tally was 463 performances.

That makes for a total of 8,169 performances, according to ibdb.com, the Broadway database, but when the New York Times reported the current production’s closure last week, it gave a different count: “In all, according to Mr. Mackintosh, the show will have run 8,202 performances on Broadway when the current production wraps up.”

According to the New York Times, “Mr. Mackintosh said in a recent interview that he was pleased with the Broadway box office performance, which he said was typical for a revival.” It also reported, “Mr. Mackintosh is planning to bring a revival of Miss Saigon to Broadway in 2017, and is working with Andrew Lloyd Webber on an expected Broadway revival of Cats.”

And for its final stand on Broadway, John Owen-Jones (pictured left) will return, once more, to the role of Jean Valjean, from March 1 to play out the run. He’s previously played it on Broadway in the show’s previous Broadway revival in 2007, and is currently back in the West End in Phantom of the Opera, another role he has played so regularly that he holds the record of any actor for the number of performances in the role (2,000 and counting).

And for its final stand on Broadway, John Owen-Jones (pictured left) will return, once more, to the role of Jean Valjean, from March 1 to play out the run. He’s previously played it on Broadway in the show’s previous Broadway revival in 2007, and is currently back in the West End in Phantom of the Opera, another role he has played so regularly that he holds the record of any actor for the number of performances in the role (2,000 and counting).

There’s currently a flurry of big openings in New York, cost with the return of The Color Purple to the Great White Way, view via London’s own Menier Chocolate Factory, coming this Thursday (December 10) and all set, I’m sure, to turn Cynthia Erivo into a Broadway superstar (see this space next week).

But the big news over the last five days was the return of two Broadway titans: playwright David Mamet and composer Andrew Lloyd Webber, both with entirely original works. It’s an amazing fact that Andrew Lloyd Webber had a Broadway production of Jesus Christ Superstar before he had a West End one of that show, and now — for the first time since that show in 1971 — he has 44 years later debuted his newest show not in the West End but on Broadway, too. It’s even more amazing that it has garnered such a positive reaction that the very next day after its opening Andrew Lloyd Webber announced a London transfer to the London Palladium next year, and a major US national tour.

It’s less surprising that David Mamet has written another poor-sounding play China Doll. His last two original Broadway efforts hardly set the town alight were Race (which opened on Broadway in 2009 and came to Hampstead in a different production in 2013) and the fast flop The Anarchist (a two-hander that starred Debra Winger and Patti LuPone and ran for just 17 performances exactly three years ago, opening December 2 and closing December 16 2012), with revivals of A Life in the Theatre and Glengarry Glen Ross in-between them (the latter also starred Al Pacino, now the main — indeed only reason — for any interest in China Doll).

Off-Broadway, one of the fastest-selling shows of the year has inevitably been Lazarus, a new musical with music by David Bowie (mostly recycled from his pop career) directed by Ivo van Hove, at New York Theatre Workshop (original home of Rent, Spring Awakening and What’s It All About?, now called Close to You in the West End). It finally opened this week, too.

Al Pacino opens in Mamet’s China Doll (After Delays)

David Mamet, whose negligible runs of his most recent Broadway plays Race (which subsequently was produced at Hampstead Theatre) and The Anarchist, is back with China Doll, which was ring-fenced against commercial failure by the casting of Al Pacino (pictured below), always a New York favourite, in the lead role of what is virtually a one-man show.

David Mamet, whose negligible runs of his most recent Broadway plays Race (which subsequently was produced at Hampstead Theatre) and The Anarchist, is back with China Doll, which was ring-fenced against commercial failure by the casting of Al Pacino (pictured below), always a New York favourite, in the lead role of what is virtually a one-man show.

But there have been reports of a lot of problems along the way to its official premiere last Friday (December 4), which was postponed by a fortnight from its originally planned date to allow for re-writes and additional rehearsal. Even Ben Brantley chronicled some of those problems in his New York Times review:

Of the plays opening on Broadway this fall, none have had a more fraught back story than China Doll, though it was always guaranteed to be a commercial slam dunk. Mr. Mamet is one of the few living American playwrights whose names have sexy marquee appeal. As for Mr. Pacino, he’s one of the last of a breed of scenery-munching titans who came of age in the 1970s, sons of Brando who turned Method into irresistible madness both on screen and onstage….

But even with weekly grosses exceeding a million dollars, China Doll, which is directed by Pam MacKinnon (a thankless task), soon found itself being circled by theater vultures for whom the scent of disaster is an aphrodisiac. The word was that Mr. Pacino couldn’t remember his lines and that audience members were walking out in baffled annoyance at intermission. The show’s original opening night was delayed by about two weeks, and Mr. Mamet was said to be rewriting copiously.

Did the delay work? Certainly the plan to open on a Friday — and therefore have the reviews buried on a Saturday when they were less likely to be read — backfired when the media, who are all invited to see final previews, ignored the stated embargo and published on Friday morning instead. And what did they find? In one of the most vicious, yet entertaining, pans of the year, Joe Dziemianowicz quoted Mamet himself in his New York Daily News review:

Did the delay work? Certainly the plan to open on a Friday — and therefore have the reviews buried on a Saturday when they were less likely to be read — backfired when the media, who are all invited to see final previews, ignored the stated embargo and published on Friday morning instead. And what did they find? In one of the most vicious, yet entertaining, pans of the year, Joe Dziemianowicz quoted Mamet himself in his New York Daily News review:

David Mamet said his new play, written for frequent muse, Al Pacino, would be “better than oral sex.”

Oral sex? “China Doll” is not even better than oral surgery.

At least for that sort of medical procedure you get painkillers. And it’s not a complete waste of time and money. ‘China Doll” — henceforth “China Dud” — is both.

On vulture.com, Jesse Green writes the most considered, nuanced and argued review of the lot, though, nailing its dramaturgical problems (“very little conflict unreels in our presence”), the ongoing appeal of its star (“Al Pacino is not an actor of much breadth but he stakes a narrow territory deeply, and that can be brilliant to watch onstage”) and especially, how the play reflects the changes in Mamet’s political ideologies over the years.

On the latter, he says,

Mamet has built what plot there is around the hypocrisy and venality of liberal politicians; the story is rigged to make Mickey, of all people, a victim. I suppose it’s not an impossible scenario — but if an innocent plutocrat is ruined, in real life, by government overreaching more than once in a decade, I’ll eat my Occupy Wall Street hat. …This gives the play the air of a one-percenter paranoiac fantasy, the kind of thing Mamet’s political opposite David Hare nailed in Skylight: “Self-pity of the rich! No longer do they simply accumulate. Now they want people to line up and thank them as well.

There’s also smart critical work from Jeremy Gerard on deadline.com, who makes similar points about the play’s poor construction but Pacino’s valiant efforts to disguise or overcome them:

Plays depending on phone conversations with unseen participants are almost always a bad idea, and China Doll is no exception. However, bad as it is (and worse still after the intermission), China Doll has one major asset, and that is the star’s unrequited commitment. It may be a dopey play that keeps tripping over its MEGO-inducing minutiae, but Pacino delivers every line with relish, with mustard, onions, the works: The hand raised, thumb against forehead, while absorbing bad news. The flash of anger in a raised voice that inspired genuine fear. The hangdog gaze of eyes that have seen it all and more and can respond only with weariness. As if apologizing to the audience, Pacino seems determined to paint a world that Mamet has lazily denied him, defined by petty backstabbing politicians, sycophantic hangers-on, tax-dodging, shelter-seeking masters of the universe and savvy corporate functionaries.

In the Wall Street Journal, however, Terry Teachout — often a contrarian — also cited the gossip surrounding the play in his review:

China Doll is a new two-man play by one of America’s best living playwrights, starring one of America’s greatest actors. In recent weeks, however, it’s also become a buzz machine: Has David Mamet, who is 68, lost his fastball? Is Al Pacino, who is 75, really reading his lines off concealed teleprompters? Over and above the gossip, it’s a matter of humiliating record that The Anarchist, Mr. Mamet’s last play, crashed and burned three years ago, closing on Broadway after 17 performances, while the one that preceded it in 2009, Race, was good enough but not up to form.

But then he went on to say,

So what about China Doll? Well, it turns out to be a strongly wrought story of considerable moral complexity, one that will hold your attention all the way to the brutal end. I can’t yet tell you whether it has the legs of American Buffalo or Glengarry Glen Ross, but I do know that I want to see it again—and while I believe Mr. Pacino has failed to do it justice, I’m still glad I got to see him give it a try.

I’m not sure that giving something a try is quite good enough at regular (non-premium) ticket prices that are up to $167.60 (or $69 in a discount offer that immediately arrived in my inbox on Friday in the wake of those predominantly negative reviews).

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s surprise Broadway hit with School of Rock

Opening a new musical on Broadway in the season of the all-conquering Hamilton was always going to be a tall order, and Andrew Lloyd Webber has even admitted as much on American television, telling viewers of the Late Show a couple of weeks ago, “Let me tell you something — I wish I’d written Hamilton!”

Opening a new musical on Broadway in the season of the all-conquering Hamilton was always going to be a tall order, and Andrew Lloyd Webber has even admitted as much on American television, telling viewers of the Late Show a couple of weeks ago, “Let me tell you something — I wish I’d written Hamilton!”

But the show he *did* write, and which opened officially on Broadway on December 5, is School of Rock, and in AM New York, the daily New York version of Metro, Matt Windman invokes the challenge, but suggests Lloyd Webber’s succeeded on his own terms: “Any Broadway musical that opens this season is bound to be in the shadow of Hamilton. School of Rock may not be a game-changer, but it is a solid, well-structured musical comedy, and you can never have enough of those.”

Amen to that! In Time Out New York, David Cote concurs — and adds some comparisons of his own. “This is one tight, well-built show… School of Rock has absorbed the diverse lessons of Rent, Spring Awakening and Matilda and passes them on to a new generation.”

He begins his four star (out of five) notice by comparing it to the original 2003 film it is based on, but then says just how well it works on stage, too.

Ever see the pitch-perfect 2003 Jack Black comedy School of Rock? Then you know what to expect from the musical version: fake substitute teacher Dewey Finn frenetically inspiring his charges to release their inner Jimi Hendrix; uptight preppy tweens learning classic riffs; and the band’s pivotal, make-or-break gig, with their overbearing parents watching in horror. We expect cute kids in uniform, a spastic Dewey and face-melting riffs—along with heart-tugging family stuff. It worked for the movie, and wow, does it work on Broadway, a double jolt of adrenaline and sugar to inspire the most helicoptered of tots to play hooky and go shred an ax. For those about to love School of Rock: We salute you.

It’s a triumph above all for the cast says David Rooney in The Hollywood Reporter:

Led by the hilarious Alex Brightman in a star-making performance that genuflects to Jack Black in the movie while putting his own anarchic stamp on the role of Dewey Finn, the show knows full well that its prime asset is the cast of ridiculously talented kids, ranging in age from nine to 13. They supply a joyous blast of defiant analog vitality in a manufactured digital world… Ultimately, what makes this show a crowdpleaser is the generosity of spirit with which it bestows the reward of cool self-realization on every last outsider and underdog — whether it’s the actual children catching an early glimpse of the adults they will become, or the eternal man-child Dewey, proudly resisting that path.

In the New York Times Ben Brantley was similarly won over the cast.

Of course, any show that serves up somber preadolescents springing to joyous life via music of their own making is bound to push buttons, especially if the kids don’t seem to be trying too hard. Me, I melted when two little girls started singing the backup chorus from Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” (one of many genial nods to classics). All the children are defined as distinct individuals but without excessive shtick. My personal favorite: the petite, poker-faced Evie Dolan as Katie the bass guitarist. But it’s up to its leading man to set a tone that mixes unwashed hedonism with reassuring wholesomeness. One step too far in one direction and audiences may feel like posting an Amber Alert; oversell the sweetness, and diabetes threatens. As Dewey, [Alex] Brightman never makes the mistake of trying to upstage his young co-stars; he gets down with, and brings out the best in, them in a performance as notable for its generosity as its virtuosity.

David Bowie back onstage (though not in person) with Lazarus

As an actor, David Bowie once did a stint — back in 1980 — as a take-over in the title role of the original Broadway production of The Elephant Man, replacing the original Philip Anglim (the play has been twice revived on Broadway since, in 2002 with the then fast-rising (but then fast-fading) Billy Crudup, then last year with Bradley Cooper in a production that transferred to the Haymarket).

Now, however, he’s written — or is at least part of — a musical, pictured left, written around some of his old songs (plus a few new) by Irish author Enda Walsh and directed by Dutch director Ivo van Hove (currently represented on Broadway but the transfer of his Young Vic production of A View from the Bridge, and next to direct a brand-new Broadway production of The Crucible).

Now, however, he’s written — or is at least part of — a musical, pictured left, written around some of his old songs (plus a few new) by Irish author Enda Walsh and directed by Dutch director Ivo van Hove (currently represented on Broadway but the transfer of his Young Vic production of A View from the Bridge, and next to direct a brand-new Broadway production of The Crucible).

It opened a sold-out run at New York Theatre Workshop on Monday December 7, to some baffled reviewers. As amNewYork critic Matt Windman describes it,

Good luck figuring out what’s going on in Lazarus, a strange, surreal musical with songs by David Bowie that is a sort of sequel to the 1963 science fiction novel The Man Who Fell to Earth, which was made into a 1976 film starring Bowie…. The art rock score consists mainly of new versions of old Bowie hits (such as “Heroes,” “Changes” and “Life on Mars?”). They are not clearly integrated into the script (by Bowie and Irish playwright Enda Walsh), so Lazarus is less a musical than an alien mystery drama combined with a psychedelic rock concert… It’s baffling as hell and unapologetically avant-garde. But if you’re up for something like this, its arresting visuals, dreamlike atmosphere and introspective Bowie songs have the potential to keep you entranced for two straight hours without intermission.

Windman is not the only critic to admit being baffled — but also simultaneously delighted. In The Guardian, Alexis Soloski writes,

It will be many years before we see a jukebox musical as unapologetically weird as Lazarus, an almost incomprehensible and oddly intriguing new play with songs by David Bowie, directed by Ivo van Hove… At moments apposite or otherwise, the band strike up a Bowie song, familiar, obscure or brand new. There’s a synthpop version of The Man Who Sold the World, an anguished take on Changes, a prettily stripped down Heroes. These are inarguably marvellous songs, but few of them are integrated into the script, which can give the play the feeling of a downbeat and occasionally alarming karaoke party. Songs that would seem to be relevant, such as Starman or Rock’n’Roll Suicide, are ignored in favour of All the Young Dudes and This Is Not America…. This should be a terrible show. It seems unlikely that it is what its collaborators imagined, and what they have created makes perilously little sense.

But, she concludes, it is performed with “such dedication and verve that it’s nearly impossible not to be persuaded and baffled and at least a little thrilled.”

That same ambivalence is obvious in Ben Brantley’s comments for the New York Times:

Ice-cold bolts of ecstasy shoot like novas through the glamorous muddle and murk of Lazarus, the great-sounding, great-looking and mind-numbing new musical built around songs by David Bowie. These transfixing moments occur when Mr. Bowie feels most palpably present — that is, when one of the show’s carefully stylized performers delivers a distinctly Bowie number in a distinctly Bowie style. Lest I create a stampede on New York Theater Workshop, let me add quickly that Mr. Bowie himself does not appear in the flesh in this sci-fi pageant of extraterrestrial angst, which has been staged by Ivo van Hove, the incredibly (and justifiably) fashionable director. But then, much of Mr. Bowie’s extraordinary longevity as a rock god has to do with the feeling that he has never really been with us ‘in the flesh.’ More than any of his peers or imitators, Mr. Bowie, an international star since the early 1970s, has always come across as his own spectral avatar, in a series of beguilingly designed alter egos who are both there and not there. Even in the midst of white-hot stage spectacle, his affect has been one of cool disassociation, matched by songs that are rhapsodies of alienation; cries of solitary pain turn into our collective pleasure, and we citizens of an anomic world swoon and think, ‘We are David Bowie’. Except that we aren’t as famous.

In The Wrap, Robert Hoffler is clearly a devoted fan: “It’s the best jukebox musical ever. That may not sound like much of a compliment, but when you put David Bowie‘s musical catalogue at the service of book writers Bowie and Enda Walsh and director Ivo van Hove, the result is more than unique. It’s terrific must-see theater.” And he concludes: “I haven’t experienced something this equal parts baffling and mesmerizing since David Lynch‘s Muholland Drive.”

But for Time Out New York, David Cote isn’t so easily impressed: “There’s precious little cheer to be had at Lazarus, which is coolly depressive and chicly designed (by Jan Verweyveld), as it circles around a dramatic void.”

He describes what he thinks may be the plot, but says,

If I got any of that wrong, complain to the creators, who don’t make Lazarus easy to follow. That the piece unfolds in dream logic, or as a fever dream, is fairly obvious in the first 10 minutes, so best to let it wash over you without worrying about sequence or connections…In lieu of a text to create narrative tension, van Hove’s stagecraft is in overdrive, stunningly augmented by Tal Yarden’s stage-filling video design and Brian Ronan’s evocative soundscape. Bowie’s songs (accompanied by an onstage band) come across beautifully, and when Lazarus works, it’s as a trippy series of live music videos. Any marriage of Bowie’s hits to a theatrical structure is bound to be unstable, especially if the end goal is not a jukebox musical, but Walsh’s lack of originality and depth makes the enterprise seem more earthbound.

Other News: Broadway bids au revoir to Les Mis (again)

It’s farewell, again, to Les Mis, whose latest Broadway incarnation — in the new, revised 25th anniversary production co-directed by Laurence Connor and James Powell — opened in March 2014. It was announced last week that it will close next year on September 9, 2016, after a reported run of 1,026 performances at the Imperial Theatre.

The 1987 Broadway transfer of Trevor Nunn and John Caird’s original London production also did the bulk of its run at the Imperial, playing for nearly 13 years there after moving from the Broadway where it played first for three years, totalling a run between them of 6680 performances. There was also a shorter-lived Broadway revival at the Broadhurst which ran at the Broadhurst for a little over a year after opening in November 2006, where its performance tally was 463 performances.

That makes for a total of 8,169 performances, according to ibdb.com, the Broadway database, but when the New York Times reported the current production’s closure last week, it gave a different count: “In all, according to Mr. Mackintosh, the show will have run 8,202 performances on Broadway when the current production wraps up.”

According to the New York Times, “Mr. Mackintosh said in a recent interview that he was pleased with the Broadway box office performance, which he said was typical for a revival.” It also reported, “Mr. Mackintosh is planning to bring a revival of Miss Saigon to Broadway in 2017, and is working with Andrew Lloyd Webber on an expected Broadway revival of Cats.”

And for its final stand on Broadway, John Owen-Jones (pictured left) will return, once more, to the role of Jean Valjean, from March 1 to play out the run. He’s previously played it on Broadway in the show’s previous Broadway revival in 2007, and is currently back in the West End in Phantom of the Opera, another role he has played so regularly that he holds the record of any actor for the number of performances in the role (2,000 and counting).

And for its final stand on Broadway, John Owen-Jones (pictured left) will return, once more, to the role of Jean Valjean, from March 1 to play out the run. He’s previously played it on Broadway in the show’s previous Broadway revival in 2007, and is currently back in the West End in Phantom of the Opera, another role he has played so regularly that he holds the record of any actor for the number of performances in the role (2,000 and counting).

In 2013, medications I interviewed John Gordon Sinclair and Ralf Little — both of whom started out acting as teenagers in youth theatre, viagra became stars young (at 19 and 18 respectively), but had no formal acting training. They were both appearing at the time in the West End return of the hit comedy The Ladykillers to the Vaudeville Theatre. Here’s the interview that resulted. (It was due to run in the SUNDAY EXPRESS but never did for lack of space or editorial will; I never found out which!).

GROWING UP WITH FAME, BUT BEING LEVEL HEADED

Mark Shenton meets John Gordon Sinclair and Ralf Little, and finds they have a lot in common.

John Gordon Sinclair and Ralf Little, who are currently starring in the West End in the hit stage comedy version of the 1955 film The Ladykillers, have a lot in common. Both of them started acting as teenagers in youth theatre, but neither of them went on to formal acting training. Both also achieved fame early on — John as the star of the 1981 British comedy Gregory’s Girl when he was just 19 and Ralf as one of the original cast of TV’s The Royle Family when he was only 18 and still doing his A Levels. Ralf subsequently dropped out of medical school, in which he was already enrolled, to continue being part of it.

“You were going to be a doctor?”, asks John (pictured left) as he hears his co-star say this. “I was mate – looking back, I had a nice set of choices but I do feel I made the right one. For the nation’s health it’s good that I moved on!”, Ralf replies.

“You were going to be a doctor?”, asks John (pictured left) as he hears his co-star say this. “I was mate – looking back, I had a nice set of choices but I do feel I made the right one. For the nation’s health it’s good that I moved on!”, Ralf replies.

They also are both writers as well as actors now – John’s first novel Seventy Times Seven, a thriller about forgiveness, was published last year, and he’s due to deliver his second novel to his publisher on July 23; while Ralf co-wrote the Sky1 series The Café with fellow actor Michelle Terry which they both also star in, and the second series of which begins transmission on July 24. As if all this serendipity wasn’t enough, their birthdays are also close to each other – John on February 4, Ralf on February 8 (though 18 years apart).

When I tell them this Ralf exclaims, “We should have learnt this out before now. We’ll have to go for a drink!”

But if their lives have followed similar arcs in many ways, they are also very different personalities: “Ralf is much cooler version of me. He’s much cooler than I was at his age!” John insists, who is quieter and reserved; Ralf is much more forward and gregarious. John adds, “I’m not very good in gangs. I prefer to sit at home reading and writing on my own. Writing my novel was much more me really.”

Ralf, on the other hand (pictured left with another co-star from the show Con O’Neill), says, “I hate being on my own. And I can’t write on my own – I don’t have the discipline, so I had to find someone to write with so there was someone else that I couldn’t let down. Michelle Terry and I did a play together and got on very well. Very often in this game you form very firm, solid friendships very quickly, because you have to – but then the job finishes and you go your separate ways, which you also have to because you can’t stay friends with everyone. But Michelle and I hit it off so well, and we both wanted to write, but the writing became almost just an excuse and framework so that we could still hang out together. We’d meet for a coffee and the only difference is that we’d bring our laptops and start writing.”

Ralf, on the other hand (pictured left with another co-star from the show Con O’Neill), says, “I hate being on my own. And I can’t write on my own – I don’t have the discipline, so I had to find someone to write with so there was someone else that I couldn’t let down. Michelle Terry and I did a play together and got on very well. Very often in this game you form very firm, solid friendships very quickly, because you have to – but then the job finishes and you go your separate ways, which you also have to because you can’t stay friends with everyone. But Michelle and I hit it off so well, and we both wanted to write, but the writing became almost just an excuse and framework so that we could still hang out together. We’d meet for a coffee and the only difference is that we’d bring our laptops and start writing.”

They showed the result to Craig Cash, who was also in The Royle Family with Ralf, “and to his surprise and ours he really liked it”; Cash has gone on to direct both series of The Café.

Meanwhile, John has been putting the finishing touches to his second novel – “I’ve got another three or four chapters to write”, he says – and Ralf points out that during breaks, “John is always incredibly diligent, going over his script and making notes. I told him you don’t need to be teacher’s pet, you’ve already got the job!” And John replies, “I was just doing the crossword!”

The job that has brought them together is a different sort of puzzle: an intricately plotted comedy about a heist that John’s character leads, with Ralf as one of his accident-prone accomplices, and their relationship with an elderly woman Mrs Wilberforce who they draw into their plot. “It’s a beautiful piece of writing,” says John. “The way it all weaves together and resolves itself is a beautiful thing.” Ralf adds, “Its full of gags, but every single character has a relationship to each other as well as with Mrs Wilberforce.”

Both actors have long specialised in comedy performances, and Ralf notes, “Maybe I should take myself a bit more seriously! It has been said by other people so I’m not being too big headed to say so, but if you can do comedy you can do anything. To make comedy work requires a lot more than people think – it takes timing, ability and hard work.” John points out the greater challenge of comedy: “If you’re trying to be funny, that defines itself – you are trying instead of being funny. And you can’t teach it – you’ve either got the timing or you haven’t.”

Both of them proved that ability early on. How does it feel being remembered so fondly for their early roles? “It’s a bit odd – I saw Gregory’s Girl recently,” says John, “and what I found quite disturbing is that I didn’t know who that guy was anymore. I couldn’t remember the thought processes going on inside his head!” (John is pictured left in the original poster for the film)

Both of them proved that ability early on. How does it feel being remembered so fondly for their early roles? “It’s a bit odd – I saw Gregory’s Girl recently,” says John, “and what I found quite disturbing is that I didn’t know who that guy was anymore. I couldn’t remember the thought processes going on inside his head!” (John is pictured left in the original poster for the film)

Ralf, for his part, is proud of The Royle Family (pictured with his co-stars below) and Two Pints of a Lager and a Packet of Crisps: “It’s an amazing thing that they’ve stayed in people’s minds for so long. It’s a positive thing for people to remember you so closely.” And John agrees: “It’s also how they remember you – it’s not for being the guy who killed your granny or shagged a dog, but for being in that great thing that they really loved.”

And now they’re both loving being back onstage. “It’s amazing to be in the West End,” says Ralf. “I came here on the first day and walked into Covent Garden in the sunshine and said what a privilege it was to be here. Being here now and having the TV series coming out, I’m really lucky. If I can’t be happy now, when can I be?” John concurs: “I was there when you said that, and it made me realise the same thing. I was a wee bit blasé about it, but you’re right – this is great!”