The 65th annual NSDF is upon us again, but as with last year’s event, it has been forced to migrate online.

As a trustee of the organisation for the last few years, I have applauded the efforts of our small core team — led by current director James Phillips, soon-to-depart executive director Kim Grant, and general manager Lizzie Melbourne — to pivot the festival so smoothly to an accessible online event, and fill it to bursting with innovative new productions, plus the usual mixture of workshops with industry specialists (including a daily morning movement class with alumni of Matthew Bourne’s New Adventures) panel discussions (like one yesterday that was titled “Is Theatre Shit? And how do we make it better?”) and masterclasses with industry leaders (later today there are events with Tasmsin Greig and director Phyllida Lloyd, open to all and entirely free).

On Monday afternoon I led a conversation with Clint Dyer, who was recently appointed deputy artistic director of the National Theatre. In the last year he became one of the few people in history to have acted, directed and written plays on its main stages.

I’ve known Clint for more than a decade and a half, ever since I interviewed him at the time he was directing The Big Life, an original British reggae/ska musical, written by Paul Sirrett and with songs by Paul Joseph, that had transferred from Stratford East to the Apollo Theatre on Shaftesbury Avenue, in 2005.

That was an event that marked him out as the first black British director of an original British musical in the West End. He gave me one of my favourite interview quotes of all time then:

“The wonderful thing about being black in this country is that you have an amazing opportunity to be the first at a lot of things.”

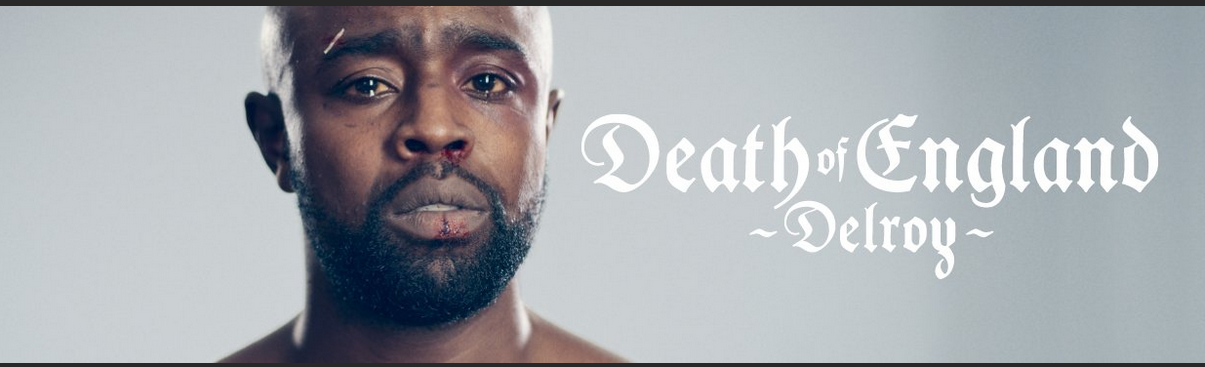

When I opened our conversation by quoting this again — and the fact that he’s continued to lead the way in being first at other things, like the aforementioned triple credit at the National after the double premieres last year of Death of England and its sequel Death of England: Delroy, both of which were directed by Dyer and co-written by him with Roy Williams, and now the first black director in second pole position there, too — he admitted that there was “a hint of sarcasm behind it” when he said it.

“I do wonder if people thought I was being quite dark about it at the time, as well. In black-and-white it looks like I am just shouting yes! But it was inside a conversation we were having about how behind we were, and how ludicrous it was that I was the first one to bring a black British musical into the West End.”

In a letter to The Stage just over two years ago, Philip Hedley (who was artistic director of Stratford East at the time the show was programmed, and acted as a valuable mentor to Dyer), wrote in response to a column by me applauding the developments at the time that saw the Bush, Stratford East, Kiln, Young Vic and Unicorn now all being led by people of colour. “I join Mark Shenton in celebrating the fact that four London theatres now have people of colour as artistic directors. Another name to add to his list is that of Suzann Mc Lean, artistic director of the recently opened Peckham Theatre. Interestingly, her appointment puts the number of women ahead of men as leaders in London’s theatres led by people of colour.”

He then quotes Dyer’s comment to me, and says, “However, despite the stream of excitedly favourable reviews he received for his direction 14 years ago, Dyer remains not only the first but also the only black British director to achieve such a breakthrough. With his very first production, Dyer hammered a crack into that particularly tough glass ceiling, but it isn’t quite shattered yet, it seems.”

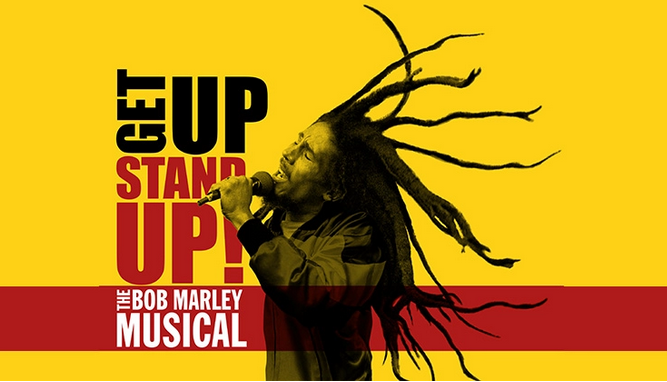

This autumn Dyer will, more than 16 years later now, return to Shaftesbury Avenue with another new show he is directing — the new Bob Marley musical Get Up, Stand Up! (pictured above), beginning performances at the Lyric from October 1. Interestingly, he was not the first choice — but Dominic Cooke, former artistic director of the Royal Court, had stepped aside, after saying that “the conversation about race has changed in theatre, as it has across society”.

As Chris Wiegend reported in The Guardian announcing this change of direction, in every sense,

“There has been increasing debate in the arts about, to quote the hit musical Hamilton, “who tells your story”. The National Theatre’s 2019 adaptation of Andrea Levy’s novel Small Island was a critical and commercial success but drew some criticism for being adapted by a white writer (Helen Edmundson) and staged by a white director (Rufus Norris).”

Cooke and Dyer had previously worked together, both as an artistic director who invited Dyer to work for him (when Cooke asked him to direct Rachel De-lahay’s The Westbridge, as part of the Royal Court’s Theatre Local season in Peckham that subsequently transferred to the Theatre Upstairs in 2011), and as director and actor (when Dyer starred in Cooke’s magnificent 2017 production of August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom at the National).

“We are friends and we had a strong relationship, and it was after he saw Death of England that I’m sure it popped into his head — though I can’t speak for him — of wanting to see the production that I would direct [of the Bob Marley show]. His moral standing was kind of way up there, anyway, right from the off, so I don’t know exactly if it was George Floyd’s murder [that led to his decision, but] it may have tipped it over the edge. After I did Death of England, my numbers went up and I was in the realm of it being a very easy thing to put into the world that I should direct it. I am not a risk. And it was quite neat, it makes sense, let’s face it, I am a British born Jamaican!”

Not that this makes it a given that he was an automatic fan of Marley’s, but he’s in his blood: “Exactly!”, replies Clint. But he says of Cooke that his allyship came out of “more than just 2020 being the year that people recognised that racism was as insidious as it is. The man he is was there before that!”

Not, either, that Cooke should necessarily be disqualified from directing a show like this, he hastens to add: “There’s a very clean and clear argument for an artist of Dominic’s ability to do it, I’m very glad that he did [stand aside], and I am really excited to do it and I am feeling very confident that it is something that will resonate.”

Interestingly, it is not the first Bob Marley musical that has been attempted in the UK — Kwame Kwei-Armah directed and wrote One Love: the Bob Marley musical that premiered at Birmingham Rep in 2017. Clint didn’t see it, but says he knows a lot about it: “From my understanding of it, his show was very much a play with a lot of music inside it, where this is an out and out musical. They are such different beasts that it shouldn’t stop the other one from having legs.”

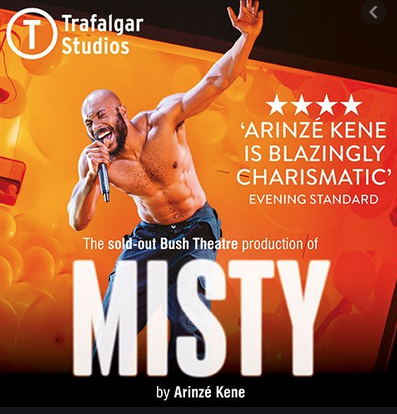

Playing Marley will be Arinzé Kene, who brought his own solo show Misty [pictured above] from the Bush to the West End’s Trafalgar Studios in 2018, that was another significant sign of changing times in the theatre. “Without a doubt! It was fantastic work by him and all at the Bush to give him the space and time to be able to create something like that.”

The theatre that we want to see and change is all about creating the opportunities for this kind of thing to happen. And that is exactly what Clint’s new appointment to the top table at the National will help facilitate and grow.

In fact his arrival there as a director and writer, as well as an actor, emerged as a result of a short film he first co-created with Roy Williams for the Royal Court.

“I think that my work at the Royal Court was very informative in getting such a risky gig. I don’t know if people felt that audiences were ready to hear the type of conversations that I was trying to have. But the fact that we had made a short film of Death of England, and the response it had, helped to open the doors to that particular conversation, and my and Roy’s desire for a British understanding of the issue of race in this country.”

The five-minute film that was made became, he says, “the bedrock to a lot of people’s interest in me, as a director and as a writer. It’s weird, isn’t it — I had been doing loads of all that, but because it went straight on the Guardian’s website, it got so much exposure and you could see what the comments were that people realised, actually this type of conversation he is trying to have is a viable one. I remember some people remarking on my place in the 90s, saying that there was no such thing as racism — people saying, ‘There was no problem, what is wrong with you?'”

I point out that this continues even today, with Ian Murray, the (now former) executive director of the Society of Editors recently claiming “it was untrue that sections of the UK press were bigoted,” after the furore ignited by Prince Harry and his wife Meghan’s suggestion that it was. Murray subsequently stepped down from his role, and the board of the organisation released a statement saying,

“The Society of Editors has a proud history of campaigning for freedom of speech and the vital work that journalists do in a democracy to hold power to account. Our statement on Meghan and Harry was made in that spirit but did not reflect what we all know: that there is a lot of work to be done in the media to improve diversity and inclusion. We will reflect on the reaction our statement prompted and work towards being part of the solution.”

Clint was unaware of this debate, but after I fill him in, he comments, “I think what is interesting about the position that we are in right now is that we are at a point of evolution. I think everyone is evolving around how to circumnavigate race in this country. For anyone to think that there is a revolution is bonkers.There is never a point in which a country, a person, a situation just changes — and then the next day everything is OK. It does not work like that. For anyone to say, “it is alright now,” is a ludicrous analysis of humanity, and how we proceed to grow as humans. It is a slow process. And that is what we are in.”

Death of England grew out of that original film into two complementary one-man plays, telling the story of the friendship of two best friends, one white (Michael, played originally by Rafe Spall) and one black (Delroy, due originally to be played by Giles Terera but replaced late in rehearsals by his understudy Michael Balogun, after Terera developed acute appendicitis).

The National gave them space at the studio, its new writing base adjoining the Old Vic, to workshop ideas for a play, and it was originally conceived for multiple actors. “We went away and then wrote a full draft and sent it in, and the response was good but there wasn’t a slot to do it in. Me and Roy have been there before! We were in the pub afterwards, and Roy came up with the idea of going back to the original format, of it being a one-person show. I’ve been around for a long time and all of the doors just seem to open. Luck came on our side as well, in the sense that another play was not ready and then there was a slot available — and so was Rafe — so we went, ‘OK, let’s do it!”

The first play opened last March in the Dorfman, though its run was brought to a premature end when the pandemic arrived and all theatres were shut down. But the lockdown had an upside: “We were commissioned to write Death of England: Delroy, and all through lock down we were writing. We did a zoom reading with Giles Terera where Rufus said yes. And he also offered me the honour of asking me to be an associate at the theatre, which was great! Then by September, we were putting on Death of England: Delroy. And soon after, he said, ‘Do you want to be deputy artistic director of the National Theatre?’ And I obviously said no! It was out of fear. I thought he had made a mistake.”

But of course he accepted in the end, after agreeing to being able to take time off to fulfil his existing commitments, including to the Bob Marley musical in the West End. He says now of his achievement in coming so far: “It’s definitely something that fills me with pride, and it’s a testament to the amount of work I put into theatre.”

Theatre, I say, has been a mainstay of his career: “Oh God, yeah. Since I was 15, I’ve been in theatre!” It was joining Stratford East’s youth theatre that ignited his passion, and would also initially become his first professional home. “What’s interesting [looking back] for me in terms of desire and commitment is that all my friends would go skiing, but not only did I not have enough money to go, it was also the same time as the Stratford East workshop, where we would devise a play and get the theatre for two nights to put it on. The idea of jeopardising that [to go skiing] was just outrageous to me. I was jealous of them in a lot of ways, but that commitment early on is why I’m where I am now.”

He later developed his taste and talent for improvisational work when he turned professional and was cast in Stratford East’s collaboration with director Mike Leigh, who devised a new play It’s a Great Big Shame at the theatre in 1993. “The whole thing is character based, which tapped into my desire to create characters and tell stories through characters, as opposed to through plot.”

It was Philip Hedley who then drove the theatre’s nurturing of not only his talent but also a wider conversation around more representation of black creatives in the theatre: “There was an understanding that there needed to be black work, but everything was going through the lens of white practitioners. This was the 1980s and early 1990s that he was thinking that way already. He set up a directors’ course for black and Asian people who wanted to direct.”

Eventually Clint put up his own hand and asked to do the course. “And he said of course.” In another conversation with Hedley, Clint remembers telling him that “musical theatre for me was going to lose its way unless it allowed modern music into the theatre.” This was, of course, long before Lin-Manuel Miranda effected a modern revolution on the Broadway musical; but Hedley took up the challenge, and took him to a seminar on musical theatre where Sarah Schlesinger from New York’s Tisch School, a graduate programme that develops writers interested in composing or writing new musicals, lectured.

“Halfway through the talk she asked if there were any questions. I am quite shy really and it was my first time in a seminar situation, but I stuck up my hand. Philip looked at me, as if he was thinking, what is he going to say? And I said, ‘As your school is a graduate school i.e. you have to have a degree before you go there, what you are saying is that Prince, Michael Jackson and George Benson would not be able to write a musical? They could not learn musical theatre writing and their music would not be appreciated in that mould, because they haven’t gone and done a course to understand what musical writing is?’ She said, ‘yes, all of those people would not be accepted and you are right: there is a massive hole’. I was not even about thinking about it on racial terms, but in terms of the style of music and who was writing it.”

Again, it’s about who is invited to participate, and barriers to entry that the guardians at the gate put in their way. Clint was invited to observe the course for a few months in New York and when he returned home, he began working on The Big Life. And thus his career as a director (and multi-hyphenate) was launched; he conceived the show, too, and brought on its writers. In due course, he also spearheaded a programme for developing new musicals at Stratford East, which bore fruit with shows like Da Boyz, a hip-hop remix of Rodgers and Hart’s The Boys from Syracuse, in turn based on Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors.

So he has long been part of a drive to draw new talents to the theatre, and explore new forms. He’s just what the National Theatre needs right now. And it was inspiring to share it with a student audience at NSDF, where the next generation of theatre makers are being nurtured to create the future of theatre, as the festival has done for the last 65 years

NSDF is running to March 31. Visit https://www.nsdf.org.uk/ to register to attend shows, debates, discussions and workshops.

Many leading people of theatre have come through its ranks its 65 years. The organisation has now launched Alumni Supporters Scheme, with NSDF Alumni Stephen Fry as patron. For further details and to sign up to support its work, visit https://www.nsdf.org.uk/support-us/alumni-supporters-scheme/