In Stephen Sondheim’s I’m Still Here (from the score for Follies, 1971), a performer called Carlotta encapsulates a lifetime of alternate struggles and triumphs, highs and lows, both professional and personal. All of our lives are, of course, lived against the background of the times we live them in. For her, these include two Hoovers — one a President, the other (unrelated), a director of the FBI.

I’ve gotten through Herbert and J Edgar Hoover

Gee, that was fun and a half

When you’ve been through Herbert and J. Edgar Hoover

Anything else is a laugh

Well, we’ve just gotten through Donald J Trump and William P Barr, and gee, we can surely echo her words:

When you’ve been through Donald J. Trump and William P Barr

Anything else is a laugh.

But just as Carlotta not only survived the Hoover era depression, she found a way to thrive:

I’ve stood on bread lines with the best

Watched while the headlines did the rest

In the depression, was I depressed?

Nowhere near

I met a big financier and I’m here

Few Sondheim songs are more full of historical references than this great anthem of sheer survival.

It’s a song I therefore return to again and again, over the years, as an example to affirm my own progress through this thing called life. Great art constantly illuminates our own lives, and reminds us of where we’ve come from, too.

On Friday night, Russell T Davies’s new (and possibly most personal) series yet, It’s a Sin (pictured above) began being given its broadcast premiere on Channel 4. I watched it contemporaneously, for the first time in a very long time, as it was being shown, instead of on catch-up or box set as I consume most series nowadays, but then was able to immediate watch the next episode, too, on All 4. so we’re definitely in a different time and place now.

But I also lived through these events contemporaneously with these fictional characters in 1980s London, as Russell T Davies (born seven months after I was) himself did. We travelled similar education paths, too — I went to Cambridge University, he to Oxford — and it was during this period that what would come to be known as HIV and AIDS started emerging.

In the TV series, one of the characters reads an early article about this new ‘gay cancer’ in HIM magazine — a blend of porn and news monthly magazine that was probably the first gay publication I ever bought (heck, it might have even been the same issue).

So the show quickly hurtled me straight back to the early eighties, where I was myself just coming out as a young gay man, like the three men portrayed in this series, and coming to terms not just with their sexuality but also with the arrival of a killer disease in their midst that seemed to be targeting our community specifically. Initial doubt, denial and disbelief filled the vacuum created by the lack of solid information about how this disease was spread and how it specifically targeted gay men are lightly touched on in the series — was it related to parrots? Poppers? Or Americans?

Eventually, we would find out that it is sexually transmitted. In a Sunday Times magazine interview profile with Russell T Davies earlier this month, Decca Aitkenhead relays this story:

“When Russell T Davies was a teenager in Swansea, he heard about a gay sauna in Newport. ‘I used to think I could go and have lots and lots of sex in that sauna right now. I was a virgin. How horny are you at 17? You’d have sex with a letterbox.’ He used to think about the sauna a lot. Eventually, one afternoon in 1980, he travelled to Newport alone, found his way to its door — but at the last moment lost his nerve and walked on by.

‘I was too scared to go in’. Not because of Aids; the disease hadn’t yet been identified. ‘I was simply scared of men and sex and becoming what I am.’ At the time Davies thought he was being a coward. Had he gone inside, he knows he would have discovered sex and loved it, and kept going back. Before long he would have said to himself: ‘Why not move to London? Its got a million gay saunas!’ He couldn’t have known what he understands today — that if he had, he would probably be dead.”

This made me think of my own very first experiences of gay sexuality. When I was 17 or 18, I would come into the West End regularly from my parents’ home in Wembley, in North West London, to see shows — usually matinees — before tubing it back home.

As a result, I inevitably found my way to Soho, where I bought that first HIM magazine. But there were also a couple of shops on Berwick Street that showed silent gay porn film reels on 16mm projectors: one called Spartacus played its own separate music soundtrack, while the one diagonally across the street called Trade was literally silent. The seats were old, battered and probably filthy, but I wasn’t paying attention to the condition of the seats: I was transfixed by the flickering images on the screen. This was the first time I’d ever seen men having sex with each other.

It gradually dawned on me that men in the audience were doing the same thing, and the single toilet stall beside the screen had a brisk trade of visitors, often with more than one going in at a time. It was here that I had my first furtive gay sexual encounter.

In September 1982 I turned 20; I was also about to go up to Cambridge University, where I would read law at Corpus Christi College. And one night I went to a bar called Harpoon Louise’s in Earl’s Court (now a branch of Wagamamamas) — and met a man, twice my age, who I exchanged phone numbers with. His name was Roger and he lived in Hitchin in Hertfordshire. He worked as a research scientist in a laboratory in the next town, Stevenage (a few years ago he died, aged 70, of cancer he’d acquired from the asbestos he worked around in that lab).

We made a date by phone to meet up in person again, and thus began a relationship that would last throughout the next three years of my University life and another seven years beyond that. His home was conveniently located roughly half way between London and Cambridge — roughly 45 minutes in either direction — so it was handy whether I was at University or back at my parents home in Wembley.

So it meant that by the time I arrived in Cambridge I already had a boyfriend, but also like Russell T Davies, I dodged a bullet by not sleeping around at that time (though I’d more than make up for any lost time in the future!) And more extraordinarily, I now realise, was that I was therefore ‘out’ from the moment I arrived there, which was rather bold at the time as I was one of only two ‘out’ gays in the village of my college (Corpus Christi) when I first arrived, the other being someone in their second year, and he’d come by my room every day to pick me up for lunch and dinner in hall. The college was an all-male, public school dominated place then, though they finally admitted women from my third year onwards; and we were the subject of much gossip and snears in the college, though seldom open hostility. (I do remember one Asian guy who I’d become friendly with during our first week entirely stopped speaking to me when he realised I was gay, though).

Anyway, by my third year the guy who’d been a year ahead of me was gone, but another person from my year suddenly came out, an English literature student called Jim. And a new gay first year called Dean found me — so were now the three (out) gays in the Corpus village. Dean soon found himself a local townie boyfriend — and would end up living with him in his council flat on the Arbury estate instead of in college rooms. Meanwhile, Jim eagerly embraced his new gay lifestyle, and would come up to London every weekend to visit clubs like Heaven and Subway, a leather bar next door to the Odeon Leicester Square that would later become the home of the Comic Strip!

In the summer after that third year, the three of us all went on that year’s London Gay Pride March (these were the days before it was the LGBTQ March), and I have this cherished picture from then above (Jim is standing between Dean and I; there’s a fourth person to the left of Dean who neither of us recognise, so we assume he must have been a friend or lover of Jim’s).

It has, however, an added poignance, as Jim would also become the first person I knew personally to be diagnosed as HIV positive, and he would subsequently die, before the decade was out. Dean and I have, however, remained close friends to this day; we still speak almost every day. (He’s now a senior television executive).

During my years at University, Roger and I made our first trip to New York in the summer of 1983, when I remember the first show I ever saw there was 42nd Street, and other shows that season included the original production of Dreamgirls that I quickly became obsessed with, seeing it three times. Also running was the original production of Nine, around which I have an eternal regret: as Broadway was already then expensive, I couldn’t afford to see everything I wanted to see, so I ‘half-timed’ some of them, which meant turning up in the interval and mingling with the crowds as they returned to their seats and taking an empty one! So I only ever saw the second half of Nine — a show that has since become a favourite.

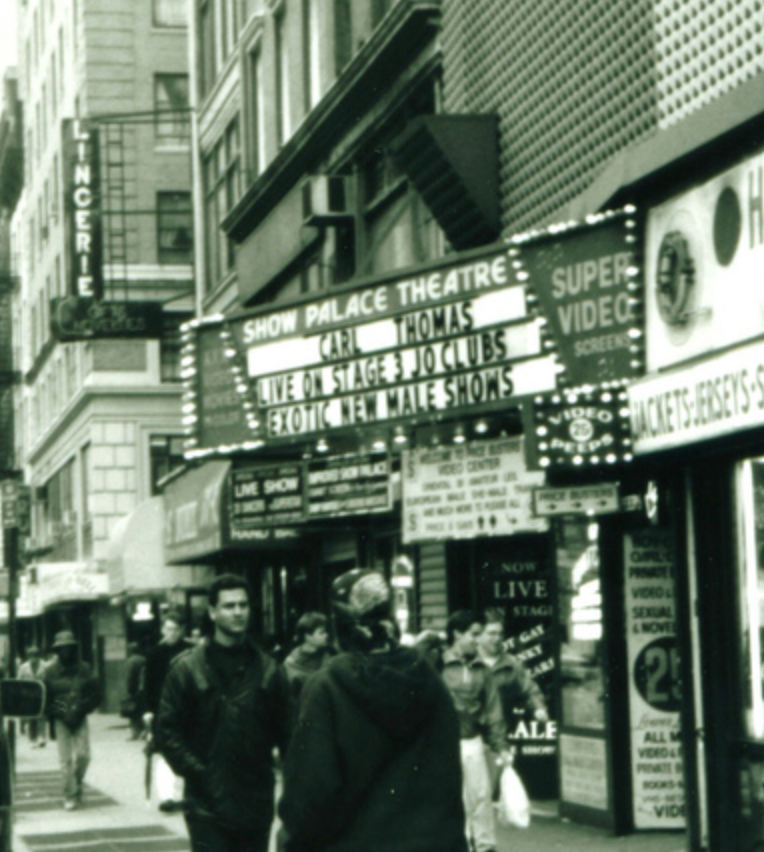

There were a couple of other ‘theatres’ Roger and I discovered on that trip: the Gaiety, just along the same block from our hotel (we were staying that trip at the Paramount on west 46th Street, then a dive, long before its subsequent lavish refurbishment), a little male strip burlesque theatre next door to the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, and the Show Palace, an even more divey strip show on Eighth Avenue located above a now demolished parade (pictured above left) that has made way for the Westin Hotel between 43rd and 44th Street, that featured appearances from gay porn stars who were flown in from LA; I remember getting a signed photo from one called Lee Ryder (pictured above right; he would also subsequently die of an AIDS-related illness). And in 1983, they also put on live sex shows at the Show Palace, which featured two or more of the strippers actually having sex with each other onstage.

So all of this was happening as a new health crisis was about to envelop the gay community. But like the characters in It’s a Sin, we were innocently unaware of its dangers. By the time Roger and I made our first pilgrimage to San Francisco a few years later, I remember being aware of a pervasive sadness as this legendarily gay city became a town full of the walking dead: people who were just skeletons, with blotches visible on their skin, everywhere. We soon found out that the disease was transmitted sexually, and the first safe sex campaigns began.

Meanwhile, I was becoming more confident as a gay man, and Roger and I started opening our relationship a bit more. But reading of Russell T Davies’s own reluctance to go inside a sauna also reminded me that I once suggested to Roger that perhaps we could go to one, to which he replied, “No, we couldn’t do that – people would laugh at you.”

I was always a bigger man, physically — not your textbook gay — and these were the days long before a separate scene evolved that catered specifically to my physical type and the men who liked us. So this was a particularly damaging remark — but again, like Russell T Davies’s reluctance to go in, might have saved me in the end.

And while It’s a Sin is apparently full of autobiographical resonances for Davies — in the Sunday Times interview, he says that part so his younger self are in all of the characters — I’m therefore proud to have shared part of my own story here. It’s only by sharing these stories that we remove the shame and stigma some of us lived through at the time, sometimes from our own partners, as I’ve noted above

But the story of It’s a Sin is also relatable whether you’re gay or not, for another, more unexpected reason, one that Davies could never have anticipated as he wrote it. As Lucy Mangan noted in her five star review of the series in The Guardian, it is this:

“This all takes on a special resonance, of course, in the time of Covid. We can empathise that bit more with the fear, uncertainty and responses rational and irrational to the emergence of a new disease.”