The pandemic has wrought many, many changes on our lives, and things will never be the same again. Some commercial producers, it appears, wanted the old order to be restored and business to proceed as normal, hence the rush to re-open as quickly as it was legally possible to do so back in November after we emerged from the second lockdown.

Shows like Everybody’s Talking About Jamie and Six re-opened side-by-side on Shaftesbury Avenue (photographed above, by Alex Wood for WhatsOnStage), and Les Mis returned, albeit in the temporary modified form of the celebrity concert version that had previously been a filler in-between the closure of the original production at the Queen’s and its re-opening in a “new”, re-staged version at the now refurbished and re-named Sondheim Theatre.

And nothing could be more ‘back to before’ than the reassuring reappearance of the now-annual Palladium panto, with its usual repertory company of returning star names like Julian Clary, Nigel Havers, Gary Wilmot and Paul Zerdin, as well as Elaine Paige making a second appearance. Even the inflated prices being commanded — with best seats at £125 — were a sign of the return of the old ‘normality’. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Of course, things weren’t quite ‘normal’, though: seating was capped at 50% of the original capacity, or 1,000 seats, whichever was the lower. So producers were hamstrung by their inability to earn back quite the same revenue. Yet clearly the were able to do the maths and make it work, even on the reduced capacity, which tipped the nod about just how much profit is being made when the shows are able to play at full capacity.

We all know, of course, how badly that experiment ended up playing out: they ended up losing even more money when the shows were summarily shut, some after only playing a handful of performances (the panto played just six, plus an invited royal dress rehearsal) before a new lockdown arrived in mid-December.

And here we are, more than a month later, and there’s no sign at all of if and when we might emerge from this one; so the theatre is, as of now, indefinitely suspended (Songs for a New World, given two concert performances in October, has now called off its planned West End transfer to the Vaudeville that was planned to run from February 5 to March 7, “due to continued uncertainty around the pandemic, though has promised it will return”, as reported by WhatsOnStage.

But if commercial theatre has simply had to shut up shop for the foreseeable and unknowable future, what about subsidised houses? They’re still getting their grants, after all; so they need to continue to try to serve their communities somehow, as well as make sure they remain financially secure enough to actually be able to come back if and when theatres are allowed to re-open.

A Guardian feature by Arifa Akbar earlier this week rounded up the artistic directors of four regional theatres, from the tiny Watermill in Newbury to the flagship Manchester venue the Royal Exchange, by way of Theatr Clwyd and Leicester’s Curve, to find out what they were doing and what challenges this year may bring. And it made for alternately encouraging and dispiriting reading.

On the one hand, Tamara Harvey and her team at Theatr Clwyd [pictured above with Executive Director Liam Evans-Ford, receiving The Stage Award for regional theatre of the year] have not only continued to make work — employing armies of freelance creatives to do so — but have also valiantly turned their theatre into a community hub, “creating a space where freelance artists can spend time with the young people that social services work with, so that together they can tell us what it is that they need”, in Harvey’s words. She’s also used the time to implement two other long-term projects: “the final design stage of our capital redevelopment, which is a total reimagining of our building; and becoming an independent trust from April, enabling us to be much more fleet of foot.”

On the other hand, Nikolai Foster at Leicester’s Curve speaks of the heartbreak of having to cancel five productions, and of an important marker for the future: “There is no way we went through the living hell of 2020 to do work that is comforting or safe.”

Yet there’s no apparent irony in the fact that, if and when they re-open, the schedule will include Disney’s new production of their first Broadway musical Beauty and the Beast, plus bringing back postponed shows Sister Act, Grease and The Wizard of Oz.

As composer and musical director Michael Roulston tweeted in response to my tweet of Foster’s quote (which I did without comment),

That, in fact, is PRECISELY what James Dacre is doing less than 40 miles away from Leicester at Northampton’s Royal and Derngate, where he is actively engaging with the future of new musicals in unprecedented ways. As they announced last month,

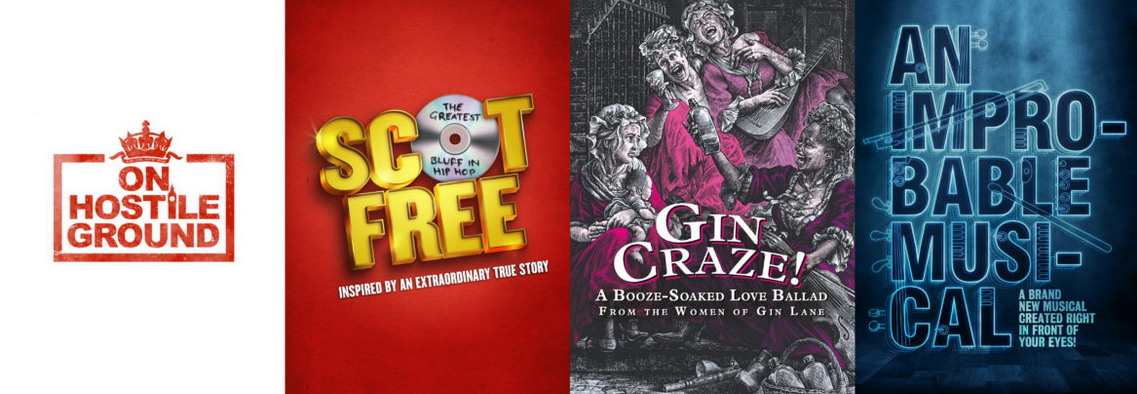

“As the culmination of a three-year project which has seen Royal & Derngate lead a national consortium of partners to support 150 artists in nurturing the creation of new musical theatre, we will be premiering three original musicals onstage and one online [pictured above]. Legendary improvised theatre company Improbable return to their roots with An Improbable Musical which takes to the Derngate stage in March. April de Angelis and Lucy Rivers’ Gin Craze! then follows in the Royal auditorium in June and Jonny Wright and Tim Gilvin’s Scot Free will be presented in concert performances in the Autumn. Meanwhile, we are supporting the release of digital musical On Hostile Ground by Juliet Gilkes Romero, Michael Henry, Darren Clark and Charlotte Westenra”.

As Dacre comments, “At the end of such a devastating year for our sector, I’m thrilled that as our theatre begins to emerge from the pandemic, we’ll do so alongside this inspiring range of artists who have reminded us of the importance of remaining ambitious, relevant and determined to create original work.”

All of that is a very long, and very welcome, way away from Grease, Sister Act and The Wizard of Oz (all of which are American in origin, and all of which have had recent commercial lives that hardly need a subsidised organisation to produce again).

But both theatres may still face some uncertainty about whether and when they can come back at all. As Paul Hart of Newbury’s Watermill Theatre [pictured above] told The Guardian,

“We have a couple of shows in mind for when we can open with social distancing but most have greater costs and we need larger audiences to bring them back. I’m nervous about how this year is going to play out; the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and Arts Council England are being optimistic about lifting restrictions but we have to be realistic to prevent the constant cycle of cancelling or postponing shows. A year from now, we will still be standing but the question is how badly damaged our organisation, and the industry, will be.”