In November, the West End was showing signs of rebooting itself, with a flurry of openings and re-openings, albeit with strict Covid-safety protocols in place; but those gains were quickly lost when the industry was forced to entirely shut down again when a new lockdown was imposed in mid-December.

On Sunday health minister Matt Hancock told Sky News we are still a “long, long, long way” from coronavirus cases being low enough for lockdown to be lifted, and the New York Times reported that last week’s disclosure that a new variant of the virus could be deadlier than the original “has silenced those who called for life to go back to normal any time soon. The British government is expected to announce in coming days that it will prolong and tighten the nationwide lockdown imposed.”

With Britain now holding the unwelcome distinction of having the highest death rate from Covid-19 per capita of any country in the world, and last week breaking our own records for daily deaths on two consecutive days, with 1,610 last Tuesday and 1,820 last Wednesday, we are in no position to even begin to think when it might be possible to ease the lockdown, let alone contemplate re-opening public gatherings at places like theatres.

Broadway, of course, hasn’t even attempted to re-open at all [a deserted 44th Street is shown above]; but last month Congress stretched out a helping hand to theatres and other live performance venues with a $15 billion fund to enable to them to survive. According to the New York Times,

“The bill allows independent entertainment businesses, like music venues and movie theaters, along with other cultural entities, to apply for grants from the Small Business Administration to support six months of payments to employees and for costs including rent, utilities and maintenance. Applicants must have lost at least 25 percent of their revenue to qualify, and those that have lost more than 90 percent will be able to apply first, within the first two weeks after the bill becomes law. Grants will be capped at $10 million.”

The bill restricts publicly traded companies and other large players from taking part: as Amy Klobuchar, the Democrat senator who proposed the bipartisan bill with her Republican counterpart John Cornyn, commented, “I wanted to make sure it didn’t benefit the Ticketmasters of the world.”

But while they’re clearing trying to level the playing field in the US for everyone affected by this deep crisis, by contrast the Sunday Times reported two days ago, “The only bespoke support for British theatre has come from the government’s $1.6bn cultural recovery fund, set up to stop artistic institutions collapsing. Industry sources calculate that less than 1 per cent of grants have gone to commercial theatre operators.”

For Andrew Lloyd Webber, who owns a fistful of London’s prime theatres including the London Palladium and Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, it is in his own best interests to see them return to use as quickly as possible; not least because he has his own latest show Cinderella lined up to open at another of this venues, the Gillian Lynne, while the Adelphi (which he co-owns with the Nederlander organisation) is to host the West End premiere of a new musical version of Back to the Future.

Yet he tells the Sunday Times,

“In these difficult times, there could be a preference for shows to open on Broadway. With the emphasis America is putting on commercial theatre, and the support they’re giving, I can see producers saying, ‘Its going to be best to put our attentions to opening on Broadway or on tour in America first. I don’t say that as some kind of threat, I see it as an observation. What would you do if you’ve got that kind of money being offered to you?”

Actually, that money isn’t being offered to new productions, but existing ones that have been affected by the shutdown; and with the claim capped at $10 million per venue, that only represents somewhere between five and ten week’s worth of revenue for a typical musical, or maybe slightly longer for a play.

But Lloyd Webber further offers this cautionary note about the near future: “Come Easter, if we can’t get back up on our feet, I think producers are going to be looking very hard at whether they will come back and whether then can risk it.”

For his part, Cameron Mackintosh — who has also long produced on both sides of the Atlantic, though he is currently a lot more active in the West End with his pre-shutdown slate including the return of Mary Poppins, the reboot of Les Miserables, The Phantom of the Opera (that he now intends to reboot as well) and Hamilton — commented to the Sunday Times that the US scheme was a “strong sign that the federal government has recognised how vital it is to city centres to have theatres back up.”

But naturally they can only do so when safety for audiences and actors is assured. The mass roll-out of vaccines may facilitate this; opening theatres only for those who are already vaccinated could be an option, but only as long as the casts, crews and theatre staff are similarly protected, so essentially we will be waiting for the entire population to be covered.

In any case, there’s another limiting factor to the theatre returning to back to where it was before the pandemic arrived: who will the audience be — and where will they come from?

As producer Richard Jordan noted last week in a column for The Stage,

“Throughout its history, the West End has leant heavily on its long-running shows: those durable bankers that are Theatreland’s economic backbone, whose brands are as strong a sales pitch to audiences as a star actor.

Therefore, long-running productions such as The Phantom of the Opera, Matilda, Wicked, Mamma Mia!, The Lion King and Les Misérables may be considered instrumental towards the West End’s recovery. Yet, these old faithfuls may face a tough comeback against newer productions, as their survival partly rests on how quickly international tourism can resume. Across all these productions, tourists buy a large number of the tickets, especially for long-running productions, so instilling confidence in travellers returning to London will be crucial.”

And he concludes,

“If tourists do not return quickly after restrictions are lifted, the West End could face its most radical shake-up in decades – an arrival of fresh new work that replaces long-running productions. This may prove to be exhilarating, but the loss of a long-running banker production could dent annual box-office figures. The process of recovery will be tough. The West End will need to attract audiences from London and across the country, and beyond. It will have to conjure up the magic of seeing a show in Theatreland, thinking hard about the casts, turning productions into events, and exclusivity. This will be crucial in re-establishing itself as an essential theatre destination.”

This could, in short, be no bad thing, and just the shot in the arm the West End — and Broadway — need to become revitalised. Yes, the long runners provide a profitable backbone to the theatre landscape in both places, but they also take too high a proportion of the valuable real estate, too: new shows literally have to fight to secure a theatre to open in, and a disproportionate amount of power therefore resides in theatrical landlords.

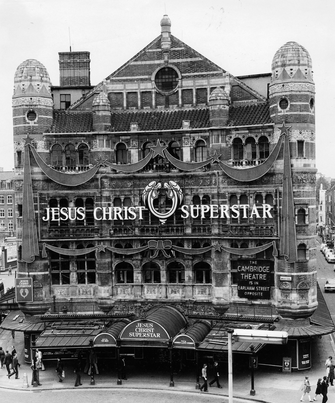

It’s difficult to remember that once upon a time a four or five year run was considered the exception, not the norm; the original 1972 West End production of Jesus Christ Superstar at the Palace Theatre (pictured above) set the all-time record for a musical run up till then by the time it closed seven years later in 1979! Meanwhile, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s next (and last) musical together Evita opened at the Prince Edward around the corner from the Palace in 1978, and closed nearly eight years later, in 1986. In each case, the prime Palace and Prince Edward Theatres were freed up for other shows.

The Palace would host a West End revivals of Oklahoma!, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Song & Dance (a double bill of two one-act musicals) and a transfer of a revival of Rodgers and Hart’s 30s musical On Your Toes from Broadway, before the original production of Les Miserables transferred there from the Barbican in 1986, where it ran until 2004, before transferring again, this time to the Queen’s where it has remained ever since, apart from a temporary hiatus when an all-star concert version was staged next door at the Gielgud while the Queen’s was being transformed into the Sondheim that it now is.

Les Miserables has, of course, now set a new West End record run, of some 36 (partly interrupted) years — interrupted partly thanks to refurbishment, partly thanks to the pandemic. But should this be the aspiration of the West End — to be a living museum of beloved titles that never close, or could we return to a world where shows recoup their initial investments, then move on after a respectable run to free the theatres for other, newer shows?