If there’s no such thing as objectivity in responses to the theatre, where does this leave the critic?

The American playwright Paula Vogel (whose How I Learned to Drive won the 1998 Pulizer prize for drama, and was due to receive its Broadway premiere last year when the pandemic struck) posed an interesting question on Twitter the other day to which I responded and she in turn replied:

That reminds me of a wonderful exchange that former theatre critic Michael Coveney reports of having with Ned Sherrin once, as Coveney remembered in a Guardian obituary of Sherrin in 2007:

“He was also an extremely funny man, with whom you were unwise to draw competitive swords (‘Back in the knife box, Miss Sharp!’ was half the title of one of his anthologies): he once accused me of ‘getting it wrong’ yet again at a theatre opening in Chichester. ‘I’m not paid to be right, I rashly countered, ‘I’m paid to be interesting’. ‘Oh dear’, flashed Ned, ‘a failure on two counts, then…’ “

But if a spectator’s failure (whether as critic or just an audience member) to meet a play on its own terms is always ours, rather than the show’s, does this mean criticism is entirely redundant nowadays? Of course, I always tell students that there’s no such thing as right and wrong in criticism — what we do is always a matter of (hopefully informed) criticism. But as Vogel suggests, it is likely to informed, as much by our passion and knowledge (or not) for what the show is about, by who we are: the baggage of assumptions and past experiences we arrive at the theatre with.

All of which is not to give us a pass on when we don’t ‘get’ a show, nor on the show either for not reaching us. We can at least explain that WE didn’t get it, and attempt to explain why.

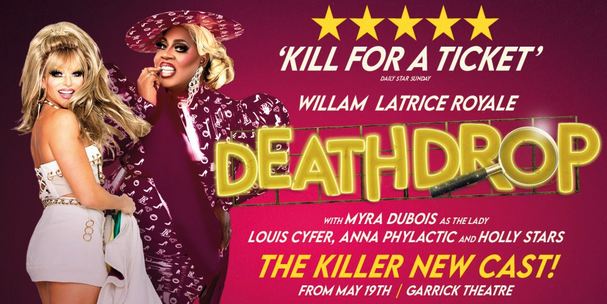

I found myself doing exactly that as I attempted to respond to Death Drop, a drag comedy that’s currently playing at the Garrick, when I finally caught up with it last week.

I duly tweeted:

I’d done exactly what Paula suggested above: “if you don’t get it, it is still valuable to read your attempt as a critic to understand why you don’t (and to note if the audience does”). I noted the audience response differed to mine.

But this opened a line of attack for the aforementioned producers of the show: not only are there quite a few of them, at least half of them took to Twitter to challenge me. Now I realise — and have previously applauded — the fact that this production is part of Nimax Theatres’ brilliant Rising Stars Festival to get young producers into the Wet End for the first time, so they’re new to this, so I won’t take their attacks personally, even if they inevitably did to mine.

One even attempted to use my own words about the audience reaction to PROVE that I was “wrong”:

And then he replied to again:

At this point I should say I wish him and his fellow co-producers well; maybe what the West End needs right now is a bit of indiscriminate laughter. I’d make it clear that it wasn’t for me; but that others clearly were having a better time of it.

I realise, too, that I may be heading into dinosaur territory myself. Last week I was interviewed by an Oxford undergrad Katie Kirkpatrick about the business of theatre criticism for a site that is rather wittily called The Indiependent, and its pretty clear that I’m a bit long in the tooth:

Shenton looks back on his days studying at Cambridge with the enthusiasm of an audience applauding as the curtain rises. He studied Law at Corpus Christi college, where he was also heavily involved in student journalism, and lists off the now celebrated actors, writers, and directors that form his contemporaries: Hugh Bonneville, Tom Hollander, Joanna Scanlan, and Simon Russell Beale all come up as big names in the Cambridge drama scene at the time. We marvel over the unchanging nature of Oxbridge student drama: a little theatrical time capsule of student celebrities, and networks of intricate and, at times, bizarre connections between people.

He warns me, however, not to become friends with actors if pursuing criticism, deciding that forming these relationships is both “inevitable” and “uncomfortable”. It’s not only actors that he remembers from Cambridge, however: Corpus Christi produced four successful theatre critics, which Shenton finds “baffling”. The Oxbridge network truly is a strange thing.

So age and background inevitably play a part in how we respond to things. Katie distils a wide-ranging conversation well, and neatly encapsulates the responsibilities of a critic as I tried to explain them:

There are a lot of questions a critic has to consider before penning their opinion. For example, “Who entitles us to say what we want to say about a show?” Shenton has decided “we earn our authority”, while remaining aware that people “can take us or leave us” and that it’s often the latter. He believes that while it’s sometimes necessary to be “fearless” and “ruthless”, “you can be honest and kind”—this seems like a good philosophy, especially in an age where making theatre is so difficult.

I hope I wasn’t too discouraging about the future, however:

He’s not optimistic about theatre criticism, however. Citing in part the “cacophony of noise” that is the internet, Shenton is convinced that it’s “impossible for people to earn a living doing it now”, and that trying to make a career out of it would be a “fool’s errand”. Theatre criticism is, he declares, a “dying industry”. It’s not all negative, though: as Shenton says, there are “loads more opportunities than ever”, and a far more diverse range of voices…. He’s both enthusiastic and skeptical of the increase in diversity in criticism, saying that “it’s past time” to diversify voices, while expressing concern about the lack of opportunities available.”

She concluded by asking me this:

I’m eager to know what the future of theatre criticism would be like in Shenton’s ideal world. While he stresses that it’s a “fantasy”, he lists three wishes. The first of these is for it to become a “paying profession again”; the second that there are “more diverse voices”, and the third that criticism is given “more space in the papers”. We can but dream.

While Shenton is confident that “journalism is finished” and there is “no viable profession left”, it hasn’t stopped him writing. He now writes primarily for his own blog, and seems pretty pleased about the decision, saying “maybe I’m not here to make money anymore”. As theatres begin to reopen, he wants to get back to New York to see new productions like Company, The Music Man, and Flying Over Sunset. It is this excitement that I remember most from our conversation: while he may have very little faith in the future of the industry, it’s very clear that Mark Shenton loves theatre, and isn’t going to stop writing about it anytime soon.

That perfectly encapsulates the happy place I currently find myself in: I’m not (yet) 60, and though I may be in an industry that has been all but extinguished as a paying profession, but nobody can take my passion away from me. And you can’t put a price — or a salary — on that.