What does the future hold for The Other Palace and the Menier Chocolate Factory?

There are some theatres whose very existence is owed to entrepreneurial and/or philanthropic excellence. And we may have taken them for granted over the last decade or more, but whose post-COVID fate is now seriously in doubt.

We always knew this was a possibility — they were already being sustained on a lifeline of passion, talent and tenacity — but after more than a year’s closure, just how easily might they bounce back?

We already know the answer for the Other Palace: since originally opening in 2012, on the former site of the Westminster Theatre which was demolished to make way for private flats on the site but which required a new theatre to be included in the building as part of the planning agreement, it has burned through (and burnt) two owners, whose current one — Andrew Lloyd Webber — has now put it up for sale. When he added it to his extensive West End portfolio in 2016, it was rebranded as “the home of new musical theatre”, and LW Theatres stated on their website,

“Here at The Other Palace we want to create a community of people who share our passion for all things musicals. We are the London space where emerging artists can try out and refine new work, offering audiences the opportunity to see musicals in development, offer feedback and help shape the musical theatre landscape. “

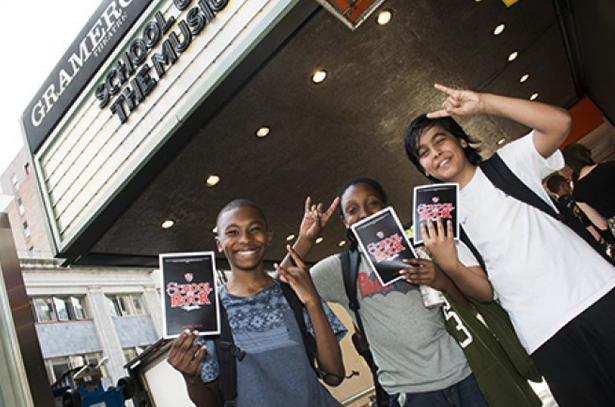

Lloyd Webber had been excited by the successful launch of his 2015 musical School of Rock in New York, which came to Broadway via a raw-bones development presentation at Off-Broadway’s Gramercy Theatre, where — without cumbersome sets and lighting in place yet — the show could be changed on the hoof. When I interviewed him ahead of its Broadway premiere for The Stage, he explained how it came about.

“We had a meeting in New York about five months ago, and everybody was saying, ‘You should go out of town with this’. But I thought, ‘Why? Why would you go to Seattle or Chicago, and then lumber yourself with designs that you find that in the end you don’t need or want, based on material we haven’t tried?’ So I came up instead with the idea of doing four weeks of rehearsals in New York, then taking a space and inviting people to come to performances as and when we wanted, which, thanks to the internet now, you can do.”

So he rented the Gramercy (where young fans are pictured above after seeing the show), and told me:

“We learned a lot about the material and a lot from the audience. When you want to make changes, you don’t have eight people telling you you can’t do it because of automation and the computers all needing to be reprogrammed. One of the major changes we were able to do at the Gramercy was to alter the order of the first four scenes entirely, so one and two became three and four, and three and four became one and two. It solved an enormous structural problem. But if we’d done that on Broadway, it would have needed two days of tech and we’d have lost two days of previews and all around the world it would be broadcast that the show was in trouble.”

He knew all about the dangers of opening shows under the full glare of public scrutiny, after his previous show Love Never Dies was effectively written off before it even opened, after an early preview was attended by online bloggers who dubbed it “Paint Never Dries” — a label that quickly and damagingly stuck. Meanwhile, fans of the original Phantom also weighted in, feeling that a property for which they had a particular sense of ownership was being somehow sullied by the sequel, and added to the chorus of doom mongers without even seeing it.

So perhaps, he thought, another idea could be to actively curt an audience’s involvement — and investment — in the development of a new show, instead of their hostility.

So buying the Other Palace was a bit of a passion project, and one in which he was able to use the downstairs studio for early private showings of Cinderella (I attended one of them, in an audience that also included Joan Collins and David Walliams), as well as a revised reading for his 2012 flop Stephen Ward (again, I attended, and the next day was invited to offer my opinions by the chief executive of Lloyd Webber’s theatrical division; I’d also been to the show’s opening night at the Aldwych Theatre, and I could only recommend bringing the curtain down on it. It felt unfixable).

The trouble with this developmental model for new musicals is that it costs money, and there’s no (immediate) return; an audience may even be persuaded to pay a small amount to attend a workshop, but it can never cover the costs. Nor, with just 312 seats to fill, could the theatre offer big returns to producers who rented the main house; costs invariably exceeded potential return. A producer would have to bank, literally, on a transfer to recoup. And the transfers weren’t exactly fast to happen.

Ironically, now that he’s declared his intention to unhitch the theatre from the rest of his portfolio, three shows first given their London lives here are now actually making their way to the West End this month and next: last night Amélie, a new British staging of the Broadway musical version of the French film that had been a fast flop in New York in 2017 but had played the Other Palace more successfully in December 2019, transferred to the Criterion, and is entirely captivating: a breath of Gaelic fresh air and quirky charm.

And later this month, Heathers — which received its British premiere at the Other Palace in 2018 before transferring to the Haymarket — will have a second run at the latter, from June 21 to September 11, and Be More Chill, the 2019 Broadway musical that was playing here in a different production in 2020 when the pandemic shut it down, will transfer to the Shaftesbury (from June 30 to September 5).

So suddenly the transfers are flying thick and fast, which may make the venue more attractive to a potential buyer. Even though the vertiginous main house fills me with dread for my personal safety every time I have visited — I’ve heard of more than one person requiring a hospital visit after falling down its steep stairs — the Other Palace is a useful addition to the theatrical landscape, with its warm, inviting and spacious bar providing a great daytime space for meetings, too, while the downstairs studio is one of the very best spaces for cabaret and intimate musical performances in town. (It was here that I first saw Benjamin Scheuer’s marvellous solo musical The Lion in 2014, and became a repeat attender — first there, then following it to repeat viewings in New York and New Haven).

Another theatre I’ve very concerned for is Southwark’s Menier Chocolate Factory. Since this incredible theatre was established in 2004 by David Babani and actor-turned-producer Danielle Tarento (who later left the organisation to go independent) it has turned out a constant stream of West End and Broadway transfers of both musicals and plays, including Sunday in the Park with George, A Little Night Music, La Cage Aux Folles and Stoppard’s Travesties all playing transatlantically, while The Color Purple bypassed a West End run and headed straight to Broadway, and other shows like Little Shop of Horrors and Merrily We Roll Along only played the West End.

While the Menier received a Cultural Recovery Fund grant of £831,830 from the first round of the £1.57 billion scheme, administered by the Arts Council, to help arts and cultural venues survive the pandemic, an existential threat to the Menier’s continued life is being posed by its landlord, who I’m told is considering redevelopment plans for the site that (naturally) include the building of new flats.

Just what this might mean for the money invested by the CRF is another question; but I assume, too, that the Menier could relocate elsewhere; yes, part of the unique magic of the theatre is the space itself — and the useful revenue it also earns from a rehearsal room it has within the building, too — but that could, potentially, be recreated elsewhere. Passion, after all, is transferable — as witness what Paul Taylor-Mills has achieved with his Turbine Theatre at Battersea, where the MT Fest of new musicals he initiated at the Other Palace has just ended, and I attended four of the eight shows being showcased.