- Love Letters (Theatre Royal, Haymarket, London SW1) **** (Booking to February 7; more details/to book: https://trh.co.uk/whatson/love-letters/)

- The Dumb Waiter (Hampstead Theatre, London NW3) **** (Booking to January 16; more details/to book: https://www.hampsteadtheatre.com/the-dumb-waiter/)

- Nine Lessons and Carols (Almeida Theatre, London N1) *** (Booking to January 9; more details/to book: https://almeida.co.uk/whats-on/nine-lessons-and-carols/2-dec-2020-9-jan-2021)

- GHBoy (Charing Cross Theatre, London WC2) *** (Booking to December 20; more details/to book: https://charingcrosstheatre.co.uk/theatre/ghboy)

With London facing the prospect of being moved into Tier 3 restrictions next week — and therefore live indoor theatre being once again prohibited — we’ve only had the briefest reprieve since the second national lockdown ended on December 2, and some theatres started opening up again from the very next day.

What a crying shame this would turn out to be for shows like Six (which moved from the Arts to the larger Lyric on Shaftesbury Avenue for a temporary residency that began last Saturday and is due to run there through to April 18, before it returns again to Newport Street), Les Miserables: The Concert (which started a sell-out run the same night) and Everybody’s Talking About Jamie (resuming performances tomorrow, December 12). All of these are neighbours on Shaftesbury Avenue, so they’re re-lighting that fabled theatrical avenue at the same time. Should it be forced to go dark again, the investment that its producers have made in bringing back life theatre may very well be lost; but I’d sooner the theatres close, of course, than the loss of life that might occur if the Covid transmission risk is sufficiently high to justify going into Tier 3.

Nevertheless, margins were already incredibly tight, with Les Mis and the Palladium panto (Pantoland, also starting tomorrow) already facing having to cap their capacities below the ones they’d originally anticipated, when the re-opening rules were changed to 50% capacity, or 1000 people, whichever is lower.

Only the Gielgud remains currently dark, as it awaits the transfer of the Broadway adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird that was due to have opened this summer but is now rescheduled to next May; further up Shaftesbury Avenue, the Palace is in the midst of a series of shorter runs, hosting shows for runs from two-show single day to five night runs. There are currently no less than seven shows listed to play there on the Nimax website in the next two months, including performances of the Union Theatre’s all-male The Pirates of Penzance this weekend.

As well as the returning productions mentioned above, some of London’s major producing theatres have also launched a slate of new productions since the restrictions were supposedly eased from December 3, including at the Almeida, Hampstead and the Bridge, while commercial limited runs for plays at Charing Cross Theatre and the Theatre Royal, Haymarket have also opened.

So suddenly critics have gone from the former famine to a sort-of feast — though its also notable that two of them are just two-handers, while a third is a three-hander (The Bridge’s A Christmas Carol, one of a slew of productions of that Dickens seasonal title that on Monday also sees the opening of a much bigger musical version at the Dominion).

And while I really want to applaud ANY producer for bringing back theatre of any shape or form, I’ve also been keenly aware that I want it to be good to justify leaving the safety and security of my home bubble and venturing out again into a world of multiple risks. Most theatres have been exemplary in their Covid safety provisions — but there’s still a risk associated with getting there and back home again.

Still, I’ve not had a week like this since March, when I used to routinely go to the theatre somewhere between five and twelve times a week (yes, really!). And I found myself suddenly in a kind of grief at its loss for the initial six months between March and September, when theatre first started returning on a limited basis with the launch of Sleepless at Wembley’s Troubadour. (Shortly after that I visited another theatre entirely — namely, an operating one, for a series of spinal surgeries — two of them scheduled, then a third that wasn’t, in the space of just fifteen days — that then took me out of circulation for a while).

THIS WEEK’S SHOWS

This week alone I’ve already seen four shows, and before the weekend is out, I’ll have seen five more (two cabarets tonight and two more tomorrow — all at the Hippodrome — and another Christmas concert featuring West End stars on Sunday at Cadogan Hall). So I’m already back at pre-pandemic levels, which as I’ve often said of myself, marks me out not so much as a theatregoers as it does a theatre addict. (In fact, I previously wrote a regular column on this website that I used to call Diary of a Theatre Addict).

So what have I seen? The two two-handers were Love Letters (transferred to the Haymarket after a five-night run at the Theatre Royal, Windsor back in October, as part of a planned season of live theatre that got curtailed by the subsequent imposition of the second national lockdown) and The Dumb Waiter (originally announced as part of Hampstead Theatre’s 60th anniversary celebrations, since Pinter’s play actually received its world premiere here in 1960, or at least in the church hall on Hampstead’s Heath Street where the theatre was originally founded).

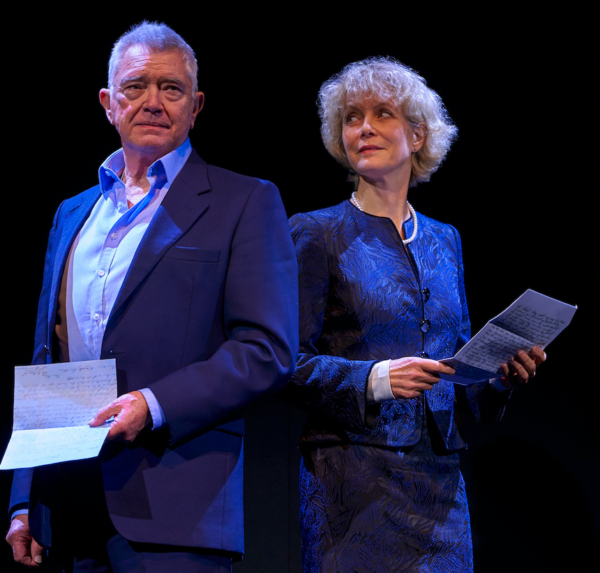

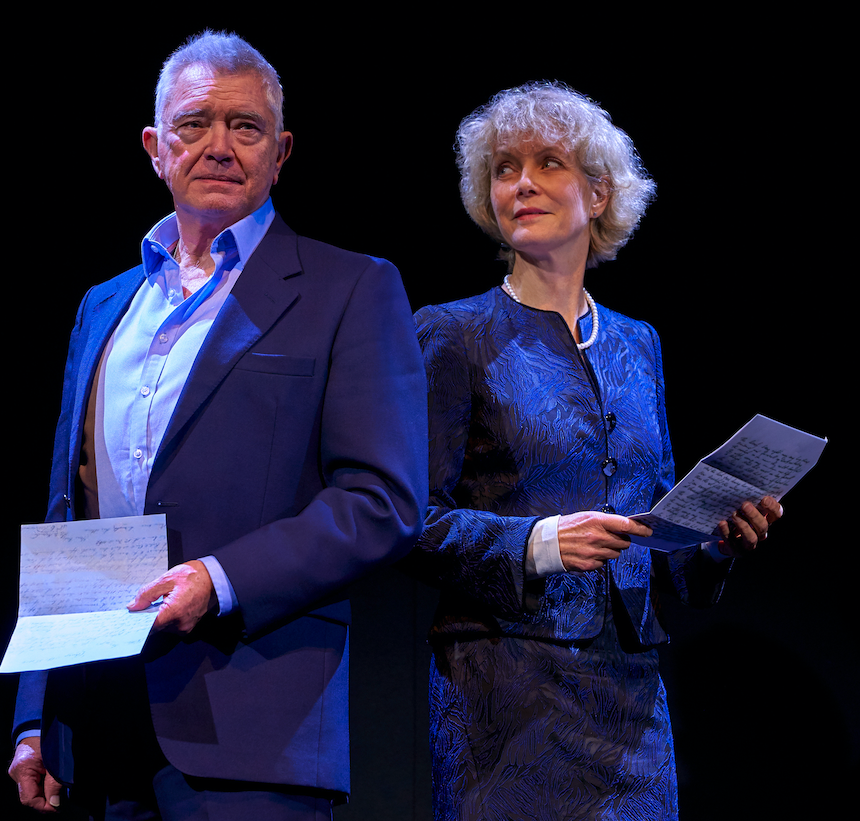

I’ve seen both of these plays multiple times before — indeed, I even saw this production of Love Letters, directed by Roy Marsden and co-starring old friends (and television colleagues on Judge John Deed) Jenny Seagrove and Martin Shaw, (pictured) at Windsor on its last night there in October. There it had been mounted after just an afternoon’s rehearsal — the actors don’t need to be off-book, but sit at solid, appropriately socially-distanced desks for the entirety.

‘ve seen both of these plays multiple times before — indeed, I even saw this production of Love Letters, directed by Roy Marsden and co-starring old friends (and television colleagues on Judge John Deed) Jenny Seagrove and Martin Shaw, (pictured above) at Windsor on its last night there in October. There it had been mounted after just an afternoon’s rehearsal — the actors don’t need to be off-book, but sit at solid, appropriately socially-distanced desks for the entirety.

But both actors — now newly and more elegantly costumed — who were already really good at Windsor have now fully settled into their roles, and the sense of shared history that they both embody offstage as well as on now spills more fully into their characters. It’s necessarily a fairly static show — the actors don’t leave their chairs — but its still waters run surprisingly deep.

They play old friends from when they first meet in second grade school, and continuing through their lives until her death — with him graduating from Ivy League university to becoming a lawyer and then a Washington-based Republican senator, while having two marriages and three sons), while she goes to art school, becomes a professional artist, and has one failed marriage which produces two daughters. That’s about all there is to it, from the point of view of plot; but it is in the gentle nudging of character that the evening acquires its power and emotional heft.

I first saw it in 1990, two years after its Broadway premiere, in a production on my first-ever visit to San Francisco, when the late Christopher Reeve and Julie Hagerty starred in it in a theatre just off Union Square (pictured above in an ad from the San Francisco Chronicle at the time); it subsequently transferred also to the West End, where it had two separate outings in 1990 and 1998. On the latter incarnation, Charlton Heston and his real-life wife Lydia starred in it also at its current home of the Haymarket, when my critical colleague David Benedict – then writing in The Independent — harshly dubbed it “the Hello! of theatregoing. There’s no kidney-shaped swimming pool, but in all other respects, AR Gurney’s little money-spinner – sorry, play — shows us not one but two celebrities in the flesh as they tell us of two intertwined lives in the intimacy of an onstage home. All very heart to heart. Or, in its last West End incarnation eight years ago, Hart to Hart, as the roles were then taken by Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers.”

But as Frankie Howerd used to say, “Titter ye not.” I happen to think that there’s more to this play than an opportunity for star names to appear on stage without the necessity to actually learn any lines. It’s actually an immensely moving portrait of life-long friendship and missed opportunities: it’s a bit like Follies without the tunes. If you surrender to its low-key charms, it is both really affecting and affectionate.

Those are not words you could use to describe The Dumb Waiter, Harold Pinter’s grim little one-act, two-actor drama about two professional hired assassins awaiting instructions in a dingy basement for who their next victim will from an unseen boss. Last seen in the West End last February, when it was the final production in Jamie Lloyd’s astonishing seven-part bill of short Pinter plays that were presented at the Pinter Theatre under the umbrella title Pinter at the Pinter, it starred Danny Dyer (who as a young man had appeared in the world premiere of Pinter’s Celebration at the Almeida, back in 2000) and Martin Freeman then.

That’s quite a bit starrier than the two, also excellent, actors Shane Zaza and Alec Newman (pictured above) being fielded by young director Alice Hamilton (according to a programme note by artistic director Roxana Silbert, Hamilton is 31 – the same age that James Roose-Evans, Hampstead’s founding artistic director – was when he directed the play’s world premiere there). It brings the play back home, albeit slightly later than its originally planned dates, which it has had to deviate not once but twice from. Most recently it was due to have had a November opening, but the arrival of the second lockdown saw it moved to this week, for a run that is booking to January 16 but may be curtailed if London goes into Tier 3. That would be a great shame after all the effort the theatre have made into putting on this sharp, riveting revival, that provides a fierce, funny, unsettling hour.

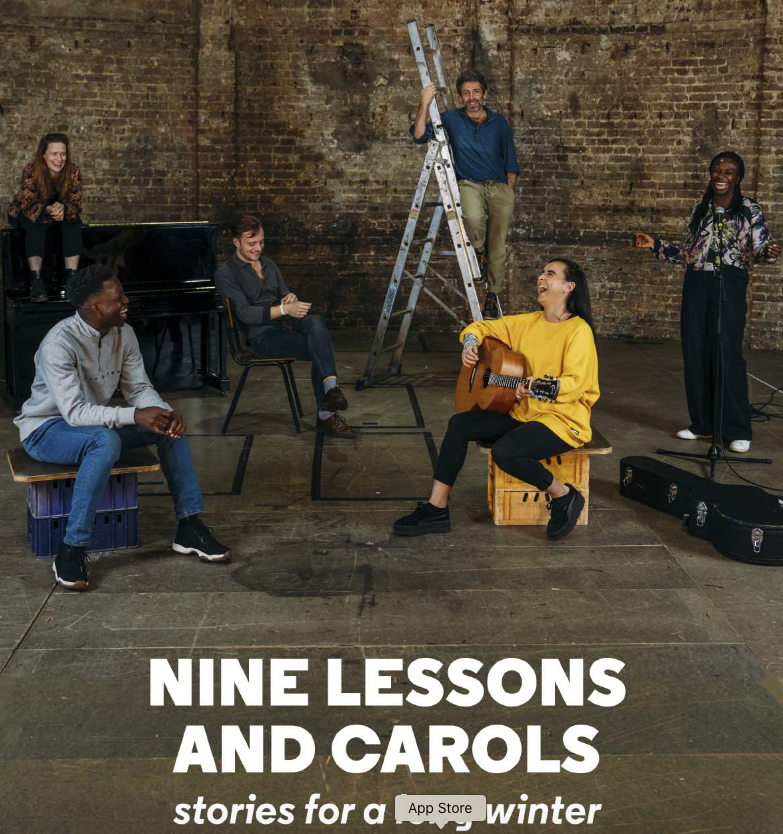

The other two plays I’ve seen this week were both new plays, both of them experimental in form and experiential in intent. At the Almeida, Nine Lessons and Carols (Stories for a Long Winter), devised by the company and written by Chris Bush, is a fragmentary, impressionistic collection of personal pandemic-related stories, with no clear linear form but that lets you soak once again in the simple joys and pleasures of hearing human beings telling their stories to each other. There were times watching it that I was reminded of Anne Washburn’s “post-electric” play Mr Burns that was premiered at the theatre in 2014, though its easier to enjoy, especially thanks to glorious singing from a company that includes Maimuna Memon and Katie Brayben (London’s original Carole King in the transfer of Beautiful from Broadway).

But it was also poignant to read a programme note from artistic director Rupert Goold headlined “Welcome Back”, in which he writes, “There have been times this year when I truly wondered if we’d ever be able to say those words again. Even writing this as the latest lockdown comes towards a conclusion feels precarious. But if you are reading this then you must be here in some capacity so once again: welcome.” The note concludes, “We hope you enjoy it and that it acts as a candle in this long winter of isolation.”

That candle is flickering with uncertainty again right now. Paul Harvard’s GHBoy, receiving its world premiere at Charing Cross Theatre, was originally scheduled to run there in November, but postponed to this month after lockdown 2 arrived. It has been fraught with further problems, not least the day before its press night, when one of the cast was injured and withdrew.

But the show went on nonetheless, when the marvellous Nicola Sloane joined the company at 2pm on the day of the press night — and then faced it with unwavering assurance (and a script in hand). This is what makes live theatre alive — and helps it live! The play itself is ambitious as it tells the poignant story of a 35-year-old gay man facing his addictions and past traumas; though it is sometimes televisual rather than theatrical in its short scenes, it is all too plausible in its sense of loss, dislocation and abandonment. It is anchored by a powerful performance from Jimmy Essex (pictured) as the protagonist; and even if he is not always quite equalled by some of those around him, this is an intense debut effort.