Last week Time Out published a beautiful online feature listing the 50 Most Beautiful Cinemas in the world, from London (five entries — Notting Hill’s Electric, Bloomsbury’s Curzon, Dalston’s Rio, BFI South Bank and a surprise entry, Mile End’s Genesis) to New York (the Paris, of course, now operated by Netflix, pictured above; and ones that I need to put on my list to visit now: the Metrograph on the Lower East Side and Village East cinema in the East Village); and from European cities like Paris (naturellement!), Amsterdam, Barcelona, Berlin, Budapest, Madrid, Rome, Vienna, and Amsterdam, to territories across America from LA and Atlanta to Chicago.

Also on the list were cinemas in more further afield places like the Shetland Islands, Cape Town, Jaipur in India, Mexico City, and Sydney, Melbourne and Auckland.

Theatres and cinemas have a lot in common: they’re places where we collect to have a shared experience of something. But whereas a film is the exactly the same thing whether you’re watching it in Berlin or Bangkok, and only the unique conditions of each of the cinemas you watch it in may change (how large the screen is, the quality of the sound etc), a theatre experience is always totally unique: even with replica productions of the same shows playing in cities around the world, performances vary from night to night and the energy in the room may fluctuate from night to night, city to city.

But it is the buildings themselves that can make the biggest difference. When I saw the premiere of the stage version of Moulin Rouge at Boston’s Emerson Colonial in the summer of 2018, the stunningly refurbished theatre was as much a part of the set as Derek McLane’s production design.

As I wrote in my original review for The Stage at the time:

“The first thing that knocks you out is the theatre itself. The stage is covered in glistening and glowing reds and features a series of heart-shaped receding proscenium panels, designed by Derek McLane. Lithe dancers writhe in a cage in the stage left box, underneath a giant statue of an elephant, while the stage right box is covered by a giant rotating windmill, recreating the one outside the actual Moulin Rouge nightclub in Paris. Ramps extend into the auditorium; Satine, the star of the cabaret, makes her first entrance flown in from the top of the stage sitting on a trapeze bar. The magnificently restored Colonial Theatre in Boston (now operated by the Ambassador Theatre Group), with its bright gold-leaf finishes, is part of the magic. You can’t really tell where the set stops and the theatre begins.”

This was immersive theatre taken to its logical and seamless conclusion. Some of that has been carried over into its Broadway home, the similarly baroque and beautiful Al Hirschfeld, proving just how important the casting of the theatre itself is. (I’m a little worried that the show has chosen as its London home the rather characterless Piccadilly Theatre, but perhaps they intend to use it as a blank canvas from which the designer can recreate the show’s whole world from scratch).

In a recent edition of my podcast series #ShenTens, I spoke about my favourite West End theatres; I also wrote a column about it here. And in my entry for my number five choice of the Palace on Shaftesbury Avenue, I wrote,

“In 2016, it became the perfect original home of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. It was once said that producers need to cast their theatres and well as their shows; this was the perfect example of that, since the theatre is the most Hogwartian in London.”

Some West End (and Broadway) theatres have toggled between being cinemas and theatres over the years, as commercial demands has dictated: the Prince Edward, for instance, was for a period of time from 1954 to 1974 became London’s exclusive home of cinerama, a (very) wide-screen experience, when it was known as the London Casino [pictured above]. It then remained as a cinema for the next 14 years, before being converted back into a theatre in 1978, and its original name restored to it, with the world premiere of Evita.

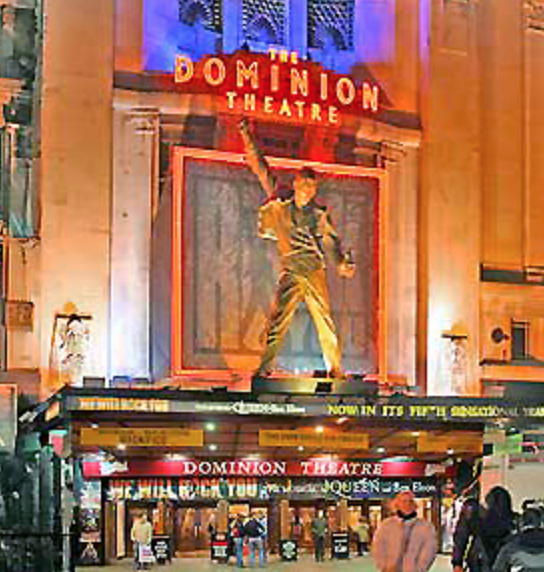

Other London theatres began their lives as cinemas before being converted to the theatrical use, like the Dominion at Tottenham Court Road which opened in 1929 (and in 1931 offered the London premiere of Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights), and which would host extended runs of the film versions of South Pacific (which ran for four years from 1958) and The Sound of Music (which ran from 1965-1968). It was used intermittently for live performance as well, especially concerts in the first half of the 1980s. (I remember seeing the incredible Shirley MacLaine here then).

It then became a home for big musicals again, especially pop-based ones, when 60s pop star Dave Clark of the Dave Clark Five co-wrote and produced the musical Time (that originally starred Cliff Richard and — in hologram form — Sir Laurence Olivier, with Richard succeeded by David Cassidy; an understudy David Ian took over in turn, and who would later become a theatre producer whose West End debut production of a new revival of Grease became a long-running hit at this theatre from 1993 to 1996, before moving in turn to the Cambridge).

In 2002, the longest run of them all began here with the world premiere of the Queen musical We Will Rock You, that ran until 2014 — against the expectations of most of the critics, myself included. As Robert Gore-Langton — now theatre critic of the Mail on Sunday — wrote in a feature in 2020, “We Will Rock You was the massive musical flop that never was. When it opened in 2002, theatre critics gave it a grievous bodily kicking. Ben Elton, who wrote the musical’s script – deemed utter twaddle – got the brunt of the duffing. ‘Only hard-core fans can save this show from an early bath,’ I wrote at the time.”

He ate humble pie by appearing in the show in a walk-on role in 2020 [pictured above] during its regional tour to Plymouth Theatre Royal, as he wrote about in the same feature. He confesses to a serious attack of nerves:

“As a legion of Plymothians made their way to their seats, little did they know there was one element – me – with potential to do to the show what Göring’s Luftwaffe did to their city…. If the show must go on, so must the critic. Standing in the wings, I wished I had taken some of that Imodium. I felt a good-luck slap on the back. Five minutes later, I sauntered into the blinding light, looking like a fossil from the mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap.

The show’s charming dance captain, Jacob, kept me close by, as promised. As Bohemians we shouted out our names. Jacob was Mick Jagger. I air-punched and announced myself as being from Event magazine, which we had agreed could have been a band name from Queen’s era.”

Rob is braver than me, though I’ve occasionally appeared on West End stages as myself — whether doing onstage interviews at the National (including, most memorably, interviewing Stephen Sondheim on the stage of the Olivier in 2004, at less than five hours notice, in front of a sell-out audience) and Theatre Royal, Haymarket (including the late, great Victoria Wood for its Masterclass series for young people), or once narrating a concert version of a musical version of Little Women at the Playhouse.

And I’ve often, of course, gone backstage to interview actors; so I’ve become familiar with many a stage door in my time.

So I’ve had some intimate, up-close experiences of the working environments of many a West End (and some Broadway) theatres, and that’s another thing that separates them from cinemas, where the only ‘backstage’ area to make it happen really is the projection booth, most of which in the current age of digital technology is entirely automated.

And yet, as we welcome the distinct possibility of returning to theatres and cinemas in the next few months, I’m determined to savour these frequently beautiful and iconic spaces for myself. (I’ve not even been to two of the five London cinemas in Time Out’s feature, Notting Hill’s Electric or Dalston’s Rio, so I could start right here. And I also wonder why on earth Time Out didn’t find space for East Finchley’s gorgeous Phoenix or Hampstead’s Everyman, though I realise — as a compiler of these sorts of lists myself — the difficulty is which ones you’d remove to include them).

I belong to a wonderful Facebook group called Theatre Architecture, which regularly features photographs of amazing cinemas as well as theatres across America. I’m even compiling a list of venues I’m determined to visit in New York — the city I visit most frequently in the US — like United Palace Theatre in upper Manhattan (pictured above left), and the George Theatre on Staten Island (above right).

Over the many years I’ve been visiting the US regularly, I’ve taken in some absolutely stunning venues — I’ve been to ever single one on Broadway, and most Off-Broadway houses, but it wasn’t until six years ago (in 2015) that I finally made a pilgrimage to BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Music) to see the transfer of a production of An Iceman Cometh from Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, starring the late Brian Dennehy and Nathan Lane, in its glorious Harvey Theatre (pictured above).

Yet I’ve not yet been back. So that needs to be fixed. And I’m also pining for a return to trip to San Francisco, and revisiting the gorgeous Castro Theatre at the top of Castro Street, a repertory movie palace where I’ve also over many visits to that city also seen a Christmas concert by the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus.