The dinosaurs that used to roam the earth were once the dominant life force on the planet, after first appearing between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (according to Wiki), before being mostly wiped out in an extinction event approximately 66 million years ago.

We’re currently in the midst of a more localised theatrical event: the extinction of theatrical dinosaurs, either by the end of their natural lifespans or cultural shifts that are rendering them redundant or past their sell-by dates. There’s a definite power shift happening behind-the-scenes in theatreland, as the old guardians of the gates have started moving on, either to the greater theatrical stage in the sky, or towards a more painful living irrelevance.

In the last few years, we’ve lost such titans of the past as Sir Peter Hall — founder of both the RSC and the NT’s first artistic director after founder Sir Laurence Olivier; Terry Hands, one of Hall’s RSC successors who also did long service at Theatr Clwyd; the legendary West End producer Duncan C Weldon, with whom Hall once partnered in his post-NT career; and the influential playwright Edward Albee, also connected to Hall, who directed the British premiere of his play A Delicate Balance for the RSC in 1969).

Hall was a great judge of character as well as director of characters: he once said of Albee,

“He makes a religion of putting people off. He loves destabilising people.”

And perhaps that’s a mark of many theatrical innovators, too, offstage as well as on: their singular vision and drive is what creates the momentum of their success; but it can also be their undoing.

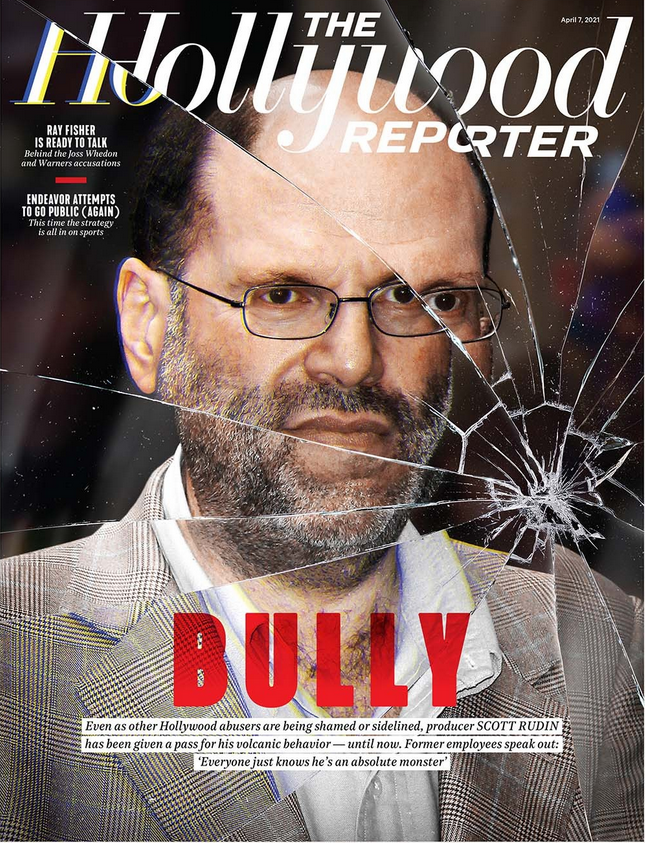

We’ve just seen a living example of this in the reports of the shocking behaviour that has engulfed Scott Rudin, Broadway’s most influential and prolific producer of the last two decades. David Merrick — the producing giant who long preceded him — had a biography written of him by New York theatre critic Howard Kissel that was entitled The Abominable Showman. The same title could be used for Rudin’s biography.

His dinosaur behaviours not only encompassed the alleged (but widely documented) routine bullying of his own young staff members, but also asserting his dominance over the rest of the theatrical species by his power plays and intimidation, as when he prevented already-licensed productions of a another stage version of To Kill a Mockingbird to proceed because of the new one he was producing for Broadway, and threatening smaller companies and community groups up and down the land (and even across the Atlantic with a planned tour of the Open Air Theatre production) with legal action to enforce his superiority. As if a Broadway production would be commercially damaged by some local school or community production of an alternative version: he was only doing it because he COULD.

And now we’ve seen Cameron Mackintosh (pictured above with composer Andrew Lloyd Webber) here in London twice in the last year throw his original investors overboard on his two biggest hits: Les Miserables and The Phantom of the Opera. Their early investment has been repaid many, many times over, of course; so they’ve forced out, apparently under the ruse in the case of Les Miserables that it an entirely new production, and in the case of Phantom that it IS entirely the original production, but needs to be recapitalised to re-open because it had to be stripped out of Her Majesty’s and the new leaner (ie. cheaper to run) touring version put in its place. And while he was about it, he also threw out the original orchestra, as well, as this touring version uses a smaller 14 piece orchestra, too.

Mackintosh, who will turn 75 this October, has built up considerable capital, in every sense, in over 50 years as a theatre producer; he may not have originated a new hit in the last thirty-plus years since Miss Saigon, but he’s been plenty busy enough maintaining and reviving his back catalogue. And he’s also become the owner of the most luxurious and well-appointed theatres in town, which has given him additional leverage as a West End power-broker. This has meant that he was able to come on board as both landlord and London producer of the already established Broadway hit Hamilton when it was seeking a West End berth.

But the million — or maybe that should be billion — dollar question is just why he needs at this point to add to his already incredible wealth. He’s already got more money than he’ll ever be able to spend. And Phantom is a large part of the reason he accumulated it in the first place. Yet he’s recently demonstrated his great insensitivity to working actors and musicians by asking why they’d want secure jobs at all, even as he’s had his own job security assured for the last fifty-plus years. As I pointed out here on Thursday, he actually said:

“I do find it odd why musicians would want to keep doing the same thing year after year. I believe we should not be holding jobs for actors or musicians ad infinitum. This is not the Civil Service, we’re creating art.”

There are other ways to create art than to ride roughshod over the very people who’ve helped you to make it, like those actors and musicians, his original investors, or the original Les Mis creative team (whose royalties ceased when the new version was put in its place).

I remember well the debacle over the original cast recording of Les Miserables, whose cast members were entitled to a small annual royalty payment for the ongoing profits it made. But when the original terms of the contract expired after 25 years, Mackintosh stopped the payments going to them. Of course, when that contract was signed no show had ever run for that period of time, so no one could have anticipated that the cast album would still be selling in significant quantities. As a matter of law, Mackintosh was right that he no longer had to pay the royalty, since that’s what they had signed to; but as a matter of moral obligation for what had created the wealth, and given the relatively low sums of money involved, it wasn’t until the likes of Michael Ball intervened that the payments were reinstated.

It wasn’t a good look; and neither now is what has happened at Phantom, especially after a year in which those very musicians haven’t been able to earn a penny.