Welcome to today’s edition of ShentonSTAGE Daily, and happy 4th of July to American readers. We keep being told we live through unprecedented times, and as the New York Times reported Donald Trump’s intention to announce his candidacy for the next Presidential race imminently — so that he can claim that the current investigations into his role in the January 6 insurgency are politically motivated — there has seldom been a bigger threat to American democracy since the nation was founded.

And with the Supreme Court now operating as an illegitimate arm of his power grab, with three of its justices appointed by him, even that historic protection is no longer there. None of us are safe: the Supreme Court has already overruled the autonomy of women’s right to choose as they seek to protect unborn life (only, of course, to let it fend for itself when it is actually born, and finds itself shot at by gunmen when it goes to school or goes to the supermarket or church). And next Clarence Thomas — a Supreme Court judge whose wife actually participated actually in the January 6 insurgency — has stated in his Roe v Wade opinion that it is not the only formerly settled law he has his sights on undermining now, but also same sex marriage and even same sex relations.

Forgive me for being so political, but we are hurtling full force towards authoritarian rule in America. So on July 4, I hope Americans are mindful of how hard they fought for independence, and how close they are to living under an oppressive regime again.

Dysfunctional America

Of course, dysfunction begins at home; and in Broadway playwright Theresa Rebeck’s new play MAD HOUSE, which received its world premiere at London’s Ambassadors Theatre last week, that is bracingly spelt out in a portrait of three adult siblings reuniting around their dying father.

The dysfunctional American family drama is, of course, a well-rehearsed dramatic trope; nobody did it finer than Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee, but Rebeck inserts diagnosed mental illness into the mix as one son spent time in an institution — and the actor playing him, American TV star David Harbour (below left, with Bill Pullman as his father and Ayiya Henry as his father’s nurse) has done, too, after a breakdown when he was younger.

So the play has the authentic air of lived experience. The British critical reaction was mostly a cool three stars (though the Evening Standard’s Farah Najib was four, and the review is duly proudly displayed in its entirety outside the theatre). Given that I began my Saturday attending a 12-step meeting of a fellowship that deals in family trauma, I’m probably the target audience for the play, though in fact I just want to “12th step” its characters to join the fellowship. Bill Pullman is gruesomely credible as the abusive patriarch, and Harbour has a brittle, wounded sensitivity as his badly damaged son.

A packed Saturday matinee proves the allure of its star billed actors, though sitting in the cramped dress circle of the Ambassadors (pictured below are my knees touching the row in front of me, and I’m only 5’9 tall), I remain desperately sad that Cameron Mackintosh didn’t go through with his plans to radically reconstruct the theatre but was pipped to the post by venture capitalist owned Ambassador Theatre Group.

This is not a theatre fit for purpose, especially when the dress circle men’s toilets were also closed by a maintenance issue. The seat I was in sells at £125; a lot to pay for such discomfort and lack of even basic facilities like a working bathroom.

Farewell, Peter Brook…..

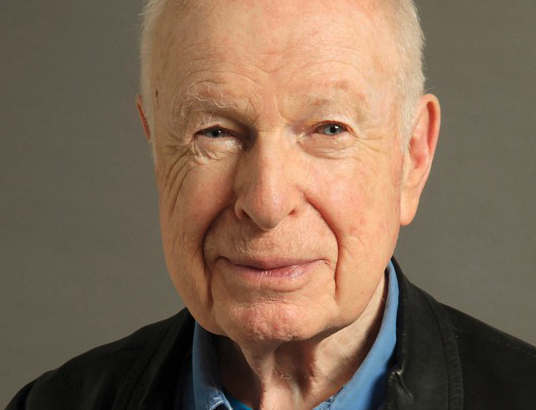

Yesterday the death was announced of a titan of world theatre, Peter Brook, who after starting out with the RSC re-shaped British approaches to Shakespearean text, but then left Britain to found his own theatre company in Paris at the Bouffes du Nord, from where he regularly launched productions that would tour the world, frequently visiting London theatres like the Young VIc and Barbican.

I missed his iconic early work like A Midsummer NIght’s Dream (1970) or his legendary collaborations with John Gielgud in Measure for Measure in 1950, The Winter’s Tale in 1952, and The Tempest in 1957; Laurence Olivier in Titus Andronicus in 1958; and Paul Scofield in King Lear in 1962 (the year I was born).

But he cast long shadows over a whole generation of British and world theatre makers, and I met him a couple of times — I’ll never forget him sitting in front of me, with his great friend and fellow theatrical influencer (in the true sense of the word, not the modern concept of twitter or YouTube luminary) Sir Peter Hall, at a memorial event for Paul Scofield. He was also the inspiration for the Empty Space Peter Brook Awards, founded by Blanche Marvin, on whose panel I sat for the last decade of their existence, until they ceased in 2017 after a 28 year run.

In 2009, awards went to Edinburgh’s Forest Fringe, producing company FUEL and the Cock Tavern (a fringe theatre then located in Kilburn, but long since defunct); as Matt Trueman (himself alas no longer a critic nowadays) wrote in The Guardian at the time, “Forest Fringe, FUEL and the Cock Tavern are different, chiefly because they don’t subscribe to accepted models of theatre. They circumnavigate the norm, always convinced – like Natwest bank – that there must be another way. Just as Forest Fringe offers a space for developing artists to experiment amid the increasing financial pressures of the Edinburgh fringe, so Adam Spreadbury-Maher,, artistic director of the Cock Tavern, has established a blossoming pub theatre without any financial backing whatsoever. Kate McGrath and Louise Blackwell of FUEL are also breaking the mould. Where most production companies focus on individual projects or scripts they believe have potential, FUEL stands by the artists themselves. The result is a longer-standing relationship that allows for genuine dialogue and development. In all these organisations, the way in which work is presented is just as important as the work itself; there are no set rules of engagement.”

I am proud that, with fellow judges that included (across my tenure) Dominic Cavendish, Lyn Gardner, Fiona Mountford, Sam Marlowe and Andrzej Lukowski, we were able to recognise and reward such outliers of the theatrical establishment.

And Peter would cast his spell, mostly by sending his wonderful assistant Nina Soufy, to read a citation, though he turned up a couple of times in person. His 2016 speech is a short but beautiful example of the utter simplicity and depth of his thought, and what made him so great. Thank you, Peter.

“In this cat’s cradle of our world today, in this tsunami of words, only one thing is crystal-clear – small is vast.

Our choice is simple – either we give up – “nothing we can do!” “it’s hopeless!” – but – this is too easy – or we stand firmly in front of the ruthless tanks, facing them, our arms outstretched. We don’t give up. What can make this possible? Take every tiny possibility and give it the best of our love and skill.

Very early on, mankind discovered a form we now call ‘Theatre’. It is the magnifying glass in which so much that’s normally hidden can appear. We never see the whole picture, we can always go deeper and deeper, wider and wider – seeing our layers and layers, dark and luminous, unveiled.

Above all, this must be shared. A tiny group is already part of mankind. Modest, no ambitions, no dreams, with the poorest of available means, crying out “Give us more money!” We are so lucky to be in this activity. Unbelievably lucky. We take a deep breath and go on again. The struggle is full of joy.”

SEE YOU IN WEDNESDAY

I’ll be back here on Wednesday. If can’t wait that long, I may also be found on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/ShentonStage/ (though not as regularly on weekends.