No Pay! No Way!

Manchester’s Royal Exchange is staging a new version of an old Dario Fo and Franca Rame 1974 play, Non Si Paga! Non Si Paga, in May, now titled No Pay? No way!, and originally seen in English as Can’t Pay? Won’t Pay!

No pay, no play, however, should be the motto in the theatre now.

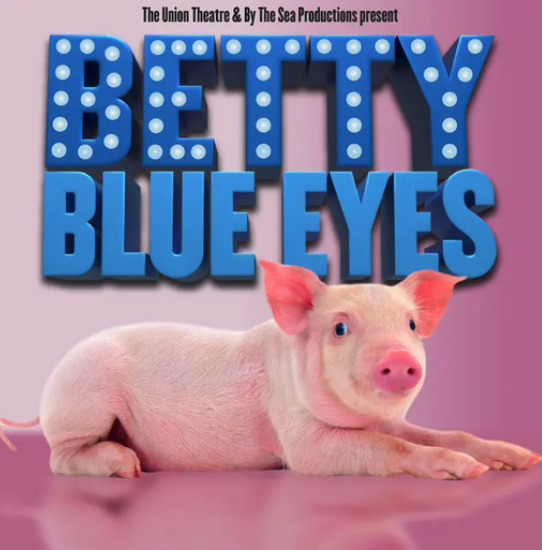

London’s Union Theatre, a Southwark venue whose work I used to regularly champion in the past for staging musicals with more passion than budget, is giving a second London outing to Stiles and Drewe’s 2011 musical Betty Blue Eyes, based on the 1984 film A Private Function, later this month (from March 29-April 22).

I’ve been trying to ascertain if the cast is actually being paid, on terms that match the Equity Fringe Agreement (or better) as it is otherwise really only an amateur production, not a professional one.

But the show’s PR (who I assume *is* being paid) hasn’t responded to two emails asking him.

So I tweeted the question on Friday.

The director’s daughter Nellie Regan — who is also in the cast — replied to say,

Which I assume means no!

And someone DM’d me to state:

“I can confirm they most definitely are not paying the actors fairly. It’s profit share and the actors get £250 in total for the WHOLE engagement (rehearsals & shows).”

Others shared the original casting breakdown, which laid out the above terms.

Of course if actors are prepared to work for peanuts, who am I to stop them? But I refuse to participate in their exploitation, so I also refuse to cover it. As all critics should. (I first took this stand five years ago, also around what the Union Theatre were doing at the time, as I wrote in The Stage then, yet here we still are). I said then, “I’m making a personal commitment not to review shows for which actors and other participants are not paid, unless they’re in a collaborative, non-hierarchical venture.”

This will not change unless individuals with power do something about it. And in my modest way, I hope that my stand might contribute to a change.

I appreciate the challenges: I know that the original Union Theatre couldn’t afford it — but in their handsome new premises, they have a busy rehearsal studio above the theatre that they earn revenue from by hiring it out, a thriving bar and in-house restaurant. So this continued model of relying on essentially free labour just doesn’t cut it anymore.

Especially as money is still being made by many other contributing parties: the director and lead creative team — all of whom have prior professional credits — will have had agreed fees budgeted for, and of course the venue (who in this case are also producing it) will call in their regular fees for renting it, to cover their many overheads. And the writers, of course, will receive the royalties they are due that their licensors (in this case the Cameron Mackintosh owned behemoth Music Theatre International) have contractually specified in return for the rights to put it on at all.

All of these will have to be covered before the promised “profit share” kicks in after the run ends, so it’s unlikely that there will be much left to go around.

Of course, MTI is only interested in the fees they are getting — it is of no concern to them whether the actors, musicians, stage management and creative team are also being remunerated. In return, they will have issued licences, scripts and scores.

Of course, it might be a more moral duty for them to find out just how the actors, musicians and crew are going to be paid, in a theatre that is as small as the Union, for a show that requires quite a sizeable cast and a live band (even if it is reduced in size).

A few years ago the Union also offered a revival of Blondel, a 1983 musical co-written by Tim Rice (with the late composer Stephen Oliver) and produced by his son. The cast was led by Connor Arnold in the title role (pictured above), and also featured Courtney Bowman.

On that occasion, I was told the actors received £700 each all-in (3 weeks rehearsals, 4 weeks run) — so £100 a week. But Rice — with his royalties for Joseph, Jesus Christ Superstar, Evita, and especially The Lion King (commercially the most lucrative musical of all time) — is surely one of the richest men in all of British theatre. He’d have even collected a (more modest) royalty for this production. Yet he happily allowed this production to happen on clearly exploitative terms. He can’t plead ignorance of it happening, as it was done partly under his direct instruction. He should be ashamed. The same applies to billionaire producer Cameron Mackintosh, who is granting the theatre the rights to present London’s second outing to one of his flop musicals through his company MTI.

Actors, of course, may often accept roles in such productions for the opportunity it presents to actually play parts that they might not otherwise get to do. And there’s always the chance of a transfer to a larger theatre (the Union previously moved A Man of No Importance to the Arts), or they may be seen and offered other work on the back of an appearance there.

But someone needs to stand up for the actors, and for the fact that “working” under such conditions excludes the many who simply could not afford to work for peanuts, thus making the industry ever more exclusive.

On Twitter, many actors have applauded my stand; a few others have sought to undermine it, claiming free choice and accusing me of failing to give them at least the exposure that might be valuable to them.

But I have a free choice too, not to endorse a corrupted system; and exposure doesn’t pay the bills in meeting the cost of living crisis.

And of course, the other key change between 2018 and now has been the Covid crisis that has brought the inequalities of the existing system into sharp relief. As Freelancers Make Theatre Work, founded in the wake of the impact on them, reported after conducting a survey,

“For those considering leaving the industry, the most common reasons for leaving were concerns about financial insecurity, poor pay and working conditions, and a growing mental health crisis, widely believe to be a ‘silent epidemic’ in the industry, necessitating the need to take ‘rights, rates and respect’ seriously. Many respondents linked low/no pay to overwork as an endemic problem impacting on mental health in ways that must be tackled. As one respondent put it, ‘I’ve never paid tax and that’s not because I have a great accountant – it’s simply that I work … 50 hours a week on average on minimum wage or less. It’s just totally unsustainable’.”

Working for just £250 for an entire rehearsal process and run of a show is an extreme example of this, and needs to be fixed. If that’s all that can be afforded, then it’s simple: just don’t do the show at all.

The Observer’s money pages yesterday had a column that was headlined: “If the British economy can’t pay better wages, then it must shrink.” Likewise, if London theatres won’t pay, then they must close.

SHOWS AHEAD IN LONDON, SELECTED REGIONAL THEATRES AND ON BROADWAY

My regularly updated feature on shows in London, selected regional theatres and on Broadway is here: https://shentonstage.com/theatre-openings-from-w-c-march-6/ Owing to technical problems, I’ve been unable to update it yet for this week.

But the coming week sees GUYS AND DOLLS opening at the Bridge tomorrow — which I’ve already seen but will be going to again on Wednesday — and a new play MARJORIE PRIME at the Menier, opening on Wednesday, that I’m going to on Thursday. There’s also a revival of Zinnie Harris’s FURTHER THAN THE FURTHEST THING, opening at the Young Vic on Thursday.

See you here on Friday

I will be back on Friday. If you can’t wait that long, I may also be found on Twitter (for the moment) here: https://twitter.com/ShentonStage/ (though not as regularly on weekends)