Another day, another theatrical social media storm. The latest person to create one is Rupert Goold, the brilliant artistic director who has turned the Almeida into one of the most influential and important theatres in all of Britain. It goes without saying that he doesn’t do it alone, and has a team around him that help to facilitate that mission.

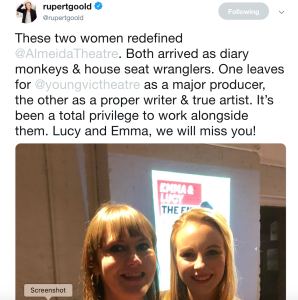

Last week, two of his staff left, and he posted a farewell tweet:

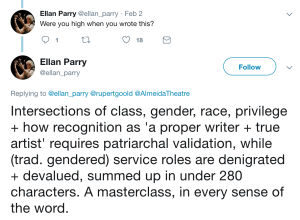

It may have been a well-intentioned goodbye, but social media immediately pounced. Ellan Parry, whose twitter bio describes herself as a “doctoral researcher, theatre designer, malcontent”, summed up the serial objections:

Others were less articulate. One freelance (male) director posted a selfie flipping him the bird.

Plenty called for him to simply resign: “Step down already please”.

These Twitter wars are becoming an increasing trend, and those of us who are active on social media find ourselves frequently in their crosshairs. As a critic, I have long believed that those of us who give criticism need also to be able to take it — it is only right that readers (or those whose work we review) have a right of reply. And one of the early pleasures of twitter was the interactions it helped to facilitate — that we were no longer writing in a vacuum, but were part of an active and frequently lively discussion around the theatre.

Critics are no longer the first or last word in critical conversations around shows. Others get there long ahead of us — not just tweeters and bloggers who see earlier previews than we do, but often in conversations that start the moment a show is announced, as witness the current furore over the recently announced David Mamet premiere Bitter Wheat, the reactions to which have been fuelled by the very reason of its existence. My colleague Lyn Gardner cites the press release in her catalogue of disapproval, let alone what the play itself may or may not have to show.

Critics are no longer the first or last word in critical conversations around shows. Others get there long ahead of us — not just tweeters and bloggers who see earlier previews than we do, but often in conversations that start the moment a show is announced, as witness the current furore over the recently announced David Mamet premiere Bitter Wheat, the reactions to which have been fuelled by the very reason of its existence. My colleague Lyn Gardner cites the press release in her catalogue of disapproval, let alone what the play itself may or may not have to show.

But nor are critics the last word in reactions around a show, but just part of an evolving conversation around them that takes place in many forums, including Twitter, which still has an unrivalled immediacy. I — and some other critics — will often post an immediate reaction after seeing a show, before we’ve even written our reviews. (The ever-present danger of this is that I do sometimes find my opinion of a show evolving as I analyse it in writing; the gut reaction of my initial tweet may well be superseded).

Next month marks my tenth anniversary of joining the platform. I initially enjoyed the sense of reaching a wider community — and actually made some good online friends who later became real-life friends, too. One was Peter Michael Marino, the American writer of a flop West End musical version of Desperately Seeking Susan who took me to task on Twitter for “ambulance chasing” a bad new musical.

As he subsequently told me, “I didn’t understand why someone who was so passionate about theatre would take any kind of pleasure in artists being unemployed. I’ve done it myself — when Spiderman – Turn off the Dark was on Broadway, I created a video that had every bad review set to the opening credits of the Spiderman cartoon, and it made it into the New York Times. But since then, I’ve become a champion of not bashing stuff — be quiet, or just tell your friend in the bar. So it doesn’t stop you and I now commiserating about seeing shitty shows together!”

Or, in other words, if you’ve not got anything nice to say, don’t say it at all. That’s not quite my role as a critic, where we can’t necessarily pull our punches: no one will thank us for not discouraging them from seeing a bad show.

But I’ve certainly learnt that performers in those shows don’t want to see these negative reactions in their timelines, and get understandably defensive when they do (so I won’t include their personal twitter handles if I’m not positive). They need, after all, to go back onstage the next night, whatever I may think of the show they’re doing; and it is certainly unkind, to say the least, to continue tweeting negatively about that show after I’ve given my initial reaction.

However, Twitter has increasingly become a bully-pit of amplified grievance too. Perhaps it’s a reflection of the powerlessness people feel in the world right now, and an abusive tweet can make someone feel they are reclaiming a tiny bit of power. Being on the receiving end of it, though, can be overwhelming: I’m only one person, the twitter mob is thousands. And the biggest mistake I’ve made is try to engage with some of the complainants; it only amplifies and prolongs the debate.

However, Twitter has increasingly become a bully-pit of amplified grievance too. Perhaps it’s a reflection of the powerlessness people feel in the world right now, and an abusive tweet can make someone feel they are reclaiming a tiny bit of power. Being on the receiving end of it, though, can be overwhelming: I’m only one person, the twitter mob is thousands. And the biggest mistake I’ve made is try to engage with some of the complainants; it only amplifies and prolongs the debate.

So even as I’m now taking active steps to reduce my twitter engagement, I’m also not going to allow myself to be bullied off it entirely. There are, I like to think, still healthy aspects to Twitter; it’s great for information, and when I lost my mother a few months ago, it was also a really inspiring place for shared experience.