By coincidence, I’ve just seen two two-handers, both of them partly featuring brother and sister siblings, and both by gay American writers who are much better known for other works, but here have been beautifully and heartbreakingly well-served by revivals of these neglected shows that bring new depth and fascination to them.

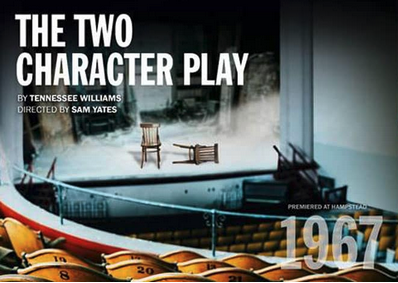

As it happens, though they’re relatively rarely seen, I’ve actually seen both of them before: in the case of Tennessee Williams’s strange but beautiful 1967 play The Two Character Play, in a 2013 off-Broadway revival in 2013; and in the case of John & Jen, in its original British premiere at the Finborough Theatre in 2007, and again in an off-Broadway revival in 2015, when it starred one of Broadway’s most vivacious singers, Kate Baldwin.

So both are shows of a singular sort of obsession for me, as they also prove to be for the directors of these revivals — Sam Yates at Hampstead, and Guy Retallack at Southwark Playhouse.

And that pays rich dividends here, as they both bring an intensity of feeling and connection to the material that is always the best reason for a director to do so something.

For Yates, it has been a long wait — according to a programme note from Hampstead artistic director Roxana Silbert, “He had long wanted to direct the play, had studied all the differing published versions, and even, at one stage, presented a rehearsed reading… What none of us know, of course, is how patient he was still going to have to be as the production was repeatedly postponed due to the pandemic. Two years on, I must salute his heroic commitment to the play and express profound gratitude for his keeping the project together throughout everything.”

Originally announced to open in April 2020 with a cast that was to have comprised David Dawson and Lyndsey Marshal, it has now reached the stage entirely recast, with the intense, brooding Zubin Varla and the utterly extraordinary, fragile yet fascinating Kate O’Flynn (pictured above) in this layered, fractured piece of meta-theatre, swapping between a play within a play and the performers of it as they struggle to get through it.

Some critics when it was originally premiered at Hampstead in 1967 (his only play ever to premiere outside of his native United States) — and a few, shamefully, even today — are still struggling to get through the play.

In The Times, Clive Davis opened his review declaring, “Sitting through this dreary, self-referential exercise in existential dread is like spending two hours watching a team of paramedics hard at work. They apply skill and stamina, yet it is all for nothing: the patient expired long before they arrived.” And in the sister Sunday Times, Quentin Letts calls it “impossible to follow,” and declares, “The audience sits trapped for two halves that threaten never to end, watching two actors jibber incomprehensible lines as they flit in and out of characters that may or may not be playing to an imagined audience. To make things ever jollier, Hampstead’s punters are ordered to wear masks. Does this theatre have a death wish?”

I’m not sure whether mask wearing – and Hampstead’s very sensible continuation of social distancing protocols in its auditorium, even though other venues have dropped them — are is relevant to whether the play works or not. But if you’re determined to have a bad time, then maybe you will. (In the same review, he also bemoans the RSC’s outdoor production of The Comedy of Errors that opened last week as well, saying that “[Guy] Lewis’s Antipholus also does repeated gags about hand sanitiser, thus taking the mickey out of an RSC that is still making patrons wear masks when they go to the loo.”

Be that as it may. Clearly here is a critic determined to strike political poses and points rather than theatrical ones. But Yates is a director who brings a full armoury of inventiveness and creativity to illuminating the play from within; and he also adds further interpretive layers with the powerful use of Ivo von Hove-esque live video projection. I was gripped, riveted and moved by this play in ways that both surprised and enthralled me.

At Southwark Playhouse, two more siblings are struggling to deal with the legacy of parental abuse in John & Jen, a chamber musical by Andrew Lippa (music) and Tom Greenwald (lyrics) with a book by both of them — that was first seen at Goodspeed Opera House in 1993 before transferring to off-Broadway in 1995. Lippa has gone on to provide rich and tuneful scores to shows like The Wild Party, The Addams Family and the under-rated Big Fish, as well as a thrilling song cycle I Am Harvey Milk, but John & Jen may just be his neglected masterpiece.

As told in a series of alternately joyous and passionate songs that reminded me at times of Maltby and Shire in their effortless melding of story and melody, grit and wit, it is spellbinding; especially when it pivots after the interval into a portrait of Jen’s relationship with her son, whom she has named after her brother.

Guy Retallack’s gorgeous production, in a superb and evocative attic set by Natalie Johnson, has stunning music accompaniment led by Chris Ma’s four-pice band. The two actors — an appropriately boyish Lewis Cornay, who is therefore perfect casting, and the always punchy and powerful Rachel Tucker — strike up an intimate and heartbreaking rapport.

Alongside the wonderful revival of Pippin now at Charing Cross, London doesn’t have a better or more moving revival in town.