We’re living through an unprecedented era of cultural wars, promulgated by the likes of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson mainly as a tool of mass distraction for the destruction of the old norms that they’re determined to advance.

But it seems that critics — the people who used to be the guardians at the gates, at least to protect, support and encourage the industries they report on — are now increasingly casting themselves as cultural warriors, too. If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em, I suppose; and there’s something to be said for the fact that maybe, just maybe, the guardians at the gate needed to be changed anyway.

It used to be — and still is, in the conventional media — that critics got their authority from being appointed to the task by an editor or arts editor: someone whose job it was to try to have writers that aligned with the values that the paper sought to promote. So you’d expect, for example, The Guardian to have a critic with a fundamentally liberal voice, while the Mail might have a reactionary one. And in this sense, Michael Billington and Quentin Letts, respectively chief critics on those papers until two years ago, were ideally cast.

In a recent forum on critics held by the Young Vic, that I reported on here, Arifa Akbar — who succeeded Billington — commented,

“I don’t for a minute doubt that we’re not all picked very carefully. I know I was, and I know that the editor-in-chief of The Guardian took a risk in replacing the irreplaceable Michael Billington with someone who looks like me. So choices are being made on a high level, I think. Wouldn’t it be great to have as a wider pool of critics high up as possible because we don’t leave who we are at the door?”

The trouble is that, however great that would be, the pool of critics in the conventional media, at least, has long been shrinking rather than expanding; so how exactly you get a wider range of critics represented among a diminishing number is actually a struggle. Certainly the arrival of Arifa at The Guardian — and Clive Davis as chief critic at The Times — has meant that criticism isn’t an exclusively all-white domain anymore in the national media.

But of course that level isn’t the only game in town anymore, either, if it ever was; The Stage for instance, is the theatre industry’s longest-established media brand, in existence for 141 years now. And although it has taken strenuous steps to maintain and expand on the critical coverage it gives to the industry, now that so many other national outlets have dropped the ball significantly on covering much more than a smattering of what’s happening beyond London, it also has to be asked just where voices of colour are to be heard in its pages?

Just occasionally, and particularly when there is a play about a subject that involves people of colour, a reviewer will be drafted in to cover it who is also of that colour; but I’d like to see those few people also invited to review other work that doesn’t match their skin tone.

Of course, it’s not just race; but there’s also the whole area of gender politics and sexuality, too. Inevitably a critic always brings themselves to the story — even, as reviews editor Natasha Tripney demonstrated yesterday in reviewing the new National Theatre filmed production of Romeo and Juliet here, to draw particular attention to how Shakespeare blames the matriarch:

“[Tamsin Greig’s Lady Capulet is the chief engineer of her daughter’s unhappiness, forcing her into a marriage with Paris while still clad in mourning black. She stands by unmoved as [Jessie Buckley’s Juliet] writhes on the floor, distraught before pleading with her to delay the marriage. Greig is majestically ice-hearted, but there’s also something uncomfortable about the way the play ladles blame on to the figure of the monstrous mother.”

Yet for all that it is still largely privileged white critics, in staff jobs, having these discussions, there’s a lot more diverse voices elsewhere. And some of these are making the critical landscape more heterogenous (and not just heteronormative).

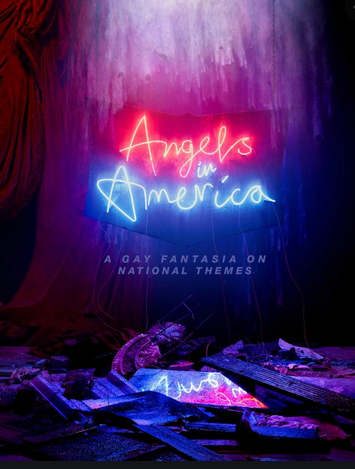

But this is also introducing new tensions amongst the ‘received’ critical wisdom, too: is Tony Kushner’s Angels in America really the masterpiece (most of us) have long thought it to be? In a feature in The Guardian published yesterday, Ryan Gilbey asked aloud of Angels in America and Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart, premiered a few years earlier, perpetuate “a white stranglehold on the portrayal of Aids in theatre?”

And he notes,

“In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) made a shocking prediction: that half of all gay and bisexual African-American men will at some point contract HIV. In this light, the white bias seems not only unjust but disproportionate.”

Michael R Jackson’s Pulitzer prize winning musical A Strange Loop not only kicks back against this narrative, but openly criticises it: Gilbey writes that Michael R Jackson’s show

“lands some punches on the white theatrical establishment: in the song Aids Is God’s Punishment, a preacher sings of burying an ‘abnormal-hearted, un-Angel-in-American black queer in the ground’. Another number pledges ‘to fill this cis-het, all-white space’ with “a portrait of a black queer face’. It can’t happen soon enough.”

By the same token, Matthew Lopez’s epic The Inheritance [pictured above] garnered this observation from Alice Savile in an otherwise complimentary four star review for Time Out:

“The night I saw the second part of The Inheritance, the role that’s usually taken by Vanessa Redgrave (Margaret) was performed by her understudy Amanda Reed instead: she brought a compassion and warmth to a part that nonetheless feels a little tacked on. Her appearance is the first sense that any women exist in this world, and she’s there to mourn, repent, and care for a suffering man, not to have her own agency.”

A playwright who drew on his own experience had set his play amongst a milieu he was himself familiar with — and the play was already nearly seven hours long. But the culture war must be fought in the trenches nonetheless to complain about the lack of representation of female voices of agency. I wonder, though, if it is equally possible to ask of Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls: where are all the men?