I had a good innings as a critic: for over 18 years, from the time I first went freelance in 2002 until the pandemic arrived last year, I actually made a decent living as a professional journalist. Over the years, my portfolio expanded and contracted, as these things do; I was variously (and sometimes simultaneously) chief theatre critic for the Sunday Express, The Stage, WhatsOnStage, What’s On in London magazine and LondonTheatre.co.uk, and was also London correspondent for a long time for Playbill.com, and contributed extensively to the BBC (both on BBC London radio and for its website), and occasionally for The Guardian website (in the halcyon days when it did regular theatre blogs) and Heat magazine (when it did tiny but welcome theatre reviews), amongst others.

Sometimes I left the publications listed above, sometimes they left me; that’s the life of a freelance journalist. Sometimes these things are entirely beyond your own control, as when there was a change of ownership — and a new editor brought in who wanted to rejig things in their own image. It’s disappointing, but you can’t take these things personally.

But thanks to the pandemic, I suddenly found myself, for the first time since 2002, without a single paying outlet; but just as significantly, it also meant I didn’t have an accredited outlet to obtain tickets on behalf of. I reinvented my critical platform as a self-publishing one, with this website and also a daily newsletter I send out to subscribers (email me at ShentonStageMaililngList@gmail.com to be added). I now depend on the kindness of strangers, or at least press agents, who guard the gates to theatres in London and beyond.

Most, but not all, have continued to invite me to their events; I accept that press allocations are a limited commodity, and not everyone who wants to be can be accommodated. Subsidised venues, in particular, have a responsibility — since they are spending public money — to make sure that their tickets are allocated only to those whose reviews matter, and not just people who want to see shows. So a qualitative assessment needs to be made on the status and standing of each critic; easy enough if they come from a publication, as the publication has its own standing, less easy for bloggers and other independent critics.

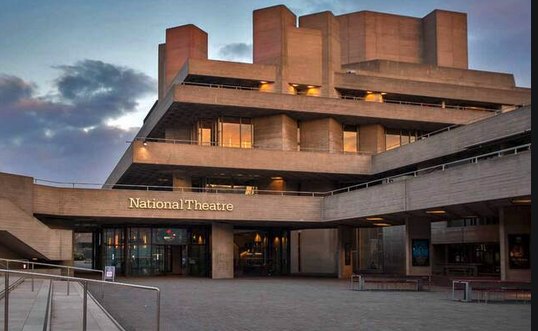

Yesterday, the National Theatre duly explained their policy to me:

“With regards to press night invitations, we tend to issue the invitation to publications who then assign their reviewer. Or we can help with review tickets directly when a review has been commissioned. Unfortunately we can’t always offer press tickets as widely as we might like to as our allocation is limited.”

Given that my own time is now limited, as I no longer live in London, this actually makes it easier for me: I don’t NEED to review shows at the National anymore. And should I want to see something, I’ll just buy a ticket — either by taking my chances on their Friday Rush scheme (this is how I secured a ticket for Afterlife for £10), or by booking in advance (as I’ve just done for a preview of The Normal Heart next month).

I can then choose to write about the shows, or not, as I see fit; I am under no obligation to do so. (When I bought a ticket to see the first preview of Bach & Sons at the Bridge, I loved the play but chose not to write about it). But buying tickets also affords me a different kind of freedom, should I choose to exercise it: I won’t necessarily have to wait for press night before commenting, a protocol which you naturally honour if you are an invited guest (though not always, as the Daily Telegraph’s recent breaking of the Hamlet embargo showed when its chief critic reviewed Ian McKellen’s very first performance, as I wrote about here at the time). If theatres can’t or won’t accommodate me as a guest, I am now free to do my own thing; if and when I buy tickets in future, I still want to respect the artistic process in which a creative team can do their work before the ‘official’ critics arrive, but if I am no longer being given the privileges of one, I can now respectfully begin the conversation about the production, whether or not it is ready for formal appraisal, as long as I make it clear that I have only seen a work-in-progress.

Of course, buying tickets — when I’m not being paid to review either — may limit the number of shows I can cover in the long run; so I hope I don’t have to buy too many. But at least I CAN buy my own tickets; others may not be so fortunate, so the theatre world could be creating more barriers to entry for voices it would prefer not to hear.

But there’s a lot more freedom to being my own publisher: I have no editor breathing hotly down my neck to toe a party line or protect a vested interest, not least the egos of their other staff and contributors. Or indeed a press agent who wants me to protect a particular client.

Press tickets have never been a right; they’re always a privilege, and we are only ever there as guests of the management (via their appointed press agents), who always have a choice of whether and to whom to extend their hospitality to, or not. (I’m not surprised I didn’t get an invite to see the revamped Phantom of the Opera last week, for instance; I’d already made my views perfectly clearly on social media that I do not intend to ever see the London production again, now that it has been musically reduced from an orchestra of 27 to just 14 players).

In 2018, one embarrassed press agent who represents the Bridge Theatre productions managed to inadvertently send a spreadsheet of the critics she’d invited to their production that year of Julius Caesar, to which director Nick Hytner compounded and amplified the error by ‘replying all’ to instruct her on where, and where not, to seat “prominent” critics. As one blogger told the Evening Standard at the time, “I am one of the leading theatre bloggers in the UK and have not been invited or allowed in to review work. It is frankly hilarious that Hytner has a code for ‘prominent’ critics and that the PR list contains no online voices. It is also startling what they’ve got wrong and where they sit people.”

Of course, critics have lately been in a fight for their very existence, and not just because of access to press tickets or not.

As I tweeted yesterday,

And playwright and theatre maker Chris Bush replied: