A lot is written about the theatre every week — not just reviews, of course, but also preview features, interviews and “think” pieces. Keeping track of them all is a hard task. I try to tweet links to features that particularly catch my eye. Starting today, I am also going to offer a weekly feature linking to some of the best ones from both sides of the pond.

Taking Risks at the Royal Opera House (but then resigning!)

In an interview with Kasper Holten (pictured left), director of opera at the Royal Opera House in last weekend’s Sunday Times (behind paywall) by Hugh Canning, he spoke of the controversy some of the work he has programmed has ignited — including the booing of Damiano Michieletto’s staging of Rossini’s William Tell that included a controversial rape scene.

In an interview with Kasper Holten (pictured left), director of opera at the Royal Opera House in last weekend’s Sunday Times (behind paywall) by Hugh Canning, he spoke of the controversy some of the work he has programmed has ignited — including the booing of Damiano Michieletto’s staging of Rossini’s William Tell that included a controversial rape scene.

He tells his interviewer Hugh Canning, “Look, I wasn’t pleased with everything that happened, but all you can do is have people here who have done exciting work in the past and try to couple them with pieces that will bring an exciting outcome. You sometimes feel that’s not exactly the outcome you had envisaged. But you have to take risks.”

He also talks of clashes between director Martin Kusej and conductor Marc Minkowski over a new production of Mozart’s Idomeneo.

It wasn’t a disaster. We had two amazing personalities, and they could have got on like a house on fire — or it could be a clash of egos. For a time, I thought it was going to be exciting. Then they started disagreeing. That’s not an excuse for the production, because I think we did reconcile the differences they had. I’m not sure audiences always appreciate the choices that go into our productions, which we don’t make merely to provoke. Was hiring Kusej and Minkowski a good idea in hindsight? Probably not. Do I regret it? No, it could have been brilliant.

In the interview, Canning writes, “Holten’s critics — one heard of clamours within the house for his removal — also need to acknowledge that these are still early days in his appointment… The jury is still out on his skills as a director, but there are clear signs that he is getting into his stride in that department; and he undoubtedly has strong ideas about how opera should be presented at Covent Garden in the 21st century, even if not everything works out as planned.”

But no sooner had this appeared, than yesterday — just three days later — he suddenly announced his departure from the company. According to new reports, he is to leave “after his contract expires in 2017, having turned down an offer of five years more in the role.”

In a statement sent to staff yesterday he said, “I love working at ROH – and with all the amazing colleagues here – and it feels very painful to let go of that in 2017. But when I moved to London, my partner and I didn’t have children. Now we do, and after much soul searching we have decided that we want to be closer to our families and inevitably that means we make Copenhagen our home where the children will grow up and go to school. It is with a very heavy heart that I send you these lines, but at the end of the day this decision has been inevitable for me.”

Daniel Evans on relishing new challenges

When Dominic Maxwell first spoke to Daniel Evans (pictured left) in the middle of November for an interview with The Times (behind paywall), published on December 7, intended to promote his new production of Show Boat that opens at Sheffield’s Crucible next week (where I will be reviewing it), Dominic asked him if he had any plans to move on. He replied at the time, “The thing is another theatre would have to be pretty amazing to beat the theatre I am currently associated with. We have three spaces [the Crucible, the Studio, and the proscenium arch Lyceum next door], we are the largest complex outside of London; it would have to be pretty special. I can’t imagine what that would be. Who knows?”

When Dominic Maxwell first spoke to Daniel Evans (pictured left) in the middle of November for an interview with The Times (behind paywall), published on December 7, intended to promote his new production of Show Boat that opens at Sheffield’s Crucible next week (where I will be reviewing it), Dominic asked him if he had any plans to move on. He replied at the time, “The thing is another theatre would have to be pretty amazing to beat the theatre I am currently associated with. We have three spaces [the Crucible, the Studio, and the proscenium arch Lyceum next door], we are the largest complex outside of London; it would have to be pretty special. I can’t imagine what that would be. Who knows?”

Well, he may not have known yet, but what he couldn’t say was that he was in-between job interviews to take over at Chichester Festival Theatre from Jonathan Church. When Maxwell catches up with Evans again on the phone on the day it was announced, Evans confesses, “I was in between the two interviews for the job when I spoke to you. Had done the first, was waiting to do the second. So I couldn’t have said anything even if I’d wanted to. You have to sign things. And I couldn’t know that I was going to get it, of course.”

So why is he moving on? Maxwell writes, “He points out that a stint of seven years, which is what his time in Sheffield will add up to when he moves south next summer, is a long one for an artistic director. In America theatre bosses tend to linger. Over here, regime change is expected every few years.”

And he then quotes Evans saying, “And I’m someone who loves new challenges. It was maybe time to move on and indeed give the theatre a chance to get some new blood. Not that my blood was running dry, it just seemed an amazing opportunity. New teams bring new energy, new challenges.”

Broadway regular Jackie Hoffman on finally getting her first lead role off-Broadway

Jackie Hoffman, soon to be 55, and a staple of Broadway and off-Broadway shows from Hairspray and Xanadu to The Addams Family and the recent On the Town, is about to play her first starring role — in an off-Broadway revival of Mary Rodgers’ musical Once Upon A Mattress (pictured left), now running at the Abrons Arts Centre though January 3.

Jackie Hoffman, soon to be 55, and a staple of Broadway and off-Broadway shows from Hairspray and Xanadu to The Addams Family and the recent On the Town, is about to play her first starring role — in an off-Broadway revival of Mary Rodgers’ musical Once Upon A Mattress (pictured left), now running at the Abrons Arts Centre though January 3.

In an interview in the New York Times (behind paywall), interviewer Alexis Soloski writes that she’s known for her ad-libbing, and “usually builds a moment into each show where she inserts her own material. [playwright David] Sedaris remembers one night during The Book of Liz, when Ms. Hoffman, playing a woman asking for directions, changed the line ‘Is it far? We have dogs in the car” to “Is it far? We have Jews in the car.'” And Sederis tells Soloski in an e-mail message, “The top of my head came off, I laughed so hard.”

Soloski also solicits a quote from Marc Shaiman, the composer of Hairspray, and he replies, “She can probably pretty much do anything you ask her to do, except dance.”

But Soloski also writes of her frustration that, “Bigger parts and greater fame are what she believes she deserves. She can’t quite fathom that she’s the only Jew in town who can’t get cast in a Fiddler on the Roof revival, and a few days after the interview she sent an unprompted email message, reading: ‘I feel the sting of too few followers on Twitter, and the frustration of taking a back seat to reality morons. I keep telling myself that good work always wins out in the end’.”

Hear, hear. And she’s an actress I would cross an ocean to see. In another preview piece in the New Yorker by Michael Schulman, he visits a costume fitting for the show. “In one corner of a rehearsal studio, the perpetually grouchy character actress Jackie Hoffman practiced running up and down a staircase in a flowing turquoise dress. In another, John Epperson, best known for his ferocious drag alter ego, Lypsinka, was choosing among bejewelled crowns. “How ironic,” Hoffman said, examining her duds. “ ‘Fiddler,’ where they’re supposed to look poor, has a budget of probably forty million. We’re supposed to look rich, and we have a budget of twelve dollars.”

XS Churchill and XL Shakespeare: does size in the theatre matter? ?

In a feature in The Guardian, Mark Lawson notes, “It struck me recently how useful it would be if theatre tickets, like clothing, came marked with a measurement of size: extra short, short, medium, long, extra long. In the last couple of weeks, London theatres have put on sale an XS (Caryl Churchill’s 45-minute Here We Go), an S (Richard Eyre’s 80-minute adaptation of Ibsen’s Little Eyolf, pictured left) and two XLs: audiences at the Royal Court for Penelope Skinner’s new play Linda, and at the Barbican for Gregory Doran’s RSC version of Henry V, are in the theatre for about three hours. At the moment, though, theatregoers seem to be faced with the equivalent of a department store that caters only for non-standard statures.”

In a feature in The Guardian, Mark Lawson notes, “It struck me recently how useful it would be if theatre tickets, like clothing, came marked with a measurement of size: extra short, short, medium, long, extra long. In the last couple of weeks, London theatres have put on sale an XS (Caryl Churchill’s 45-minute Here We Go), an S (Richard Eyre’s 80-minute adaptation of Ibsen’s Little Eyolf, pictured left) and two XLs: audiences at the Royal Court for Penelope Skinner’s new play Linda, and at the Barbican for Gregory Doran’s RSC version of Henry V, are in the theatre for about three hours. At the moment, though, theatregoers seem to be faced with the equivalent of a department store that caters only for non-standard statures.”

He goes on to note, “These days, the most popular theatrical form – possibly a compromise between the average 60 minutes of TV drama and the 120 or so minutes at which the majority of movies come in – is a brisk 75-90 minutes, with no drinks in the middle. This structure has almost become the default for new plays, although the shift in theatrical fashion is shown by the fact that Little Eyolf, which originally followed common late-19th-century practice of division into three acts, has been streamlined by Richard Eyre in his splendid new version at the Almeida into the linear 80-minute, single-location piece that Ibsen might well have written if he were a young dramatist under commission today. The question of whether length matters is almost as sensitive an issue in theatre as in personal advice pages for men.”

David Greig, from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to The Lorax

Scottish playwright David Greig — and soon to take over as artistic director of Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum Theatre — has adapted Seuss’s The Lorax (picured left) for the stage, where it opens at the Old Vic next week on December 14.

Scottish playwright David Greig — and soon to take over as artistic director of Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum Theatre — has adapted Seuss’s The Lorax (picured left) for the stage, where it opens at the Old Vic next week on December 14.

In an interview with Alex O’Connell for The Times (behind paywall), Greig said that he was initially reluctant to take it on: “Ordinarily I would have said no because it was very short notice. Then Matthew [Warchus, the Old Vic’s artistic director] said, ‘You just need another 20 minutes of material.’ So I thought, ‘I love Dr Seuss and it sounds like something I can do in a couple of afternoons.’ But the moment you sit down and think about it, you are still adapting a book.”

And it turns out it is an iconic book, particularly in America. As O’Connell puts it,

The Lorax is one of those books that has become a tabula rasa for every possible protest group. Indeed, a log-felling company in California wrote a riposte to it, explaining that felling could be environmentally friendly.

“In America it does have history but the only way to do this was to make it fun and to celebrate it,” says Greig. “The message, if you like it, is there: look after your resources, chill out sometimes, not everything has to multiply a thousand times, it’s OK to do things small. That’s a lesson about life. It is also about ageing. The Lorax doesn’t want things to change. But things do change. He’s not sanctimonious, he’s colourful and rhyming and silly.”

Last month David Cameron revealed that The Lorax was one of his favourite children’s books. I wonder what Greig, a strong “pro” voice in the Scottish independence debate, made of that. “I was surprised in some ways,” he admits. “But, I mean, he likes the Smiths, he’s allowed to like what he likes.”

The show was developed across five months – quite a contrast to the five years that Charlie and the Chocolate Factory took before it even went into rehearsal, which Greig (pictured left) also wrote the adaptation of. Grieg comments of it, “Charlie is a factory. I don’t mean that in a bad way: it’s like Willy Wonka’s, it’s delightful and insane and hundreds of Oompa-Loompas work to make it happen — and I felt like Charlie in the process, wide-eyed. I went from never having done any big-scale work to doing the biggest-scale work it is possible to do. [With The Lorax] I am now the only person in the room for whom this is a really small-scale project.” And Charlie is still in his life now, as he works on the Broadway version and is involved in casting of new Willy Wonkas. He says, “I realised the other day that there will come a point when Charlie is no longer in my life. It has already been a decade that I’ve been involved and it could be longer, I hope. It’s been a generous gift.”

The show was developed across five months – quite a contrast to the five years that Charlie and the Chocolate Factory took before it even went into rehearsal, which Greig (pictured left) also wrote the adaptation of. Grieg comments of it, “Charlie is a factory. I don’t mean that in a bad way: it’s like Willy Wonka’s, it’s delightful and insane and hundreds of Oompa-Loompas work to make it happen — and I felt like Charlie in the process, wide-eyed. I went from never having done any big-scale work to doing the biggest-scale work it is possible to do. [With The Lorax] I am now the only person in the room for whom this is a really small-scale project.” And Charlie is still in his life now, as he works on the Broadway version and is involved in casting of new Willy Wonkas. He says, “I realised the other day that there will come a point when Charlie is no longer in my life. It has already been a decade that I’ve been involved and it could be longer, I hope. It’s been a generous gift.”

That extends, of course, to money: “Yes, to have a period of time in your life where you feel free to do what you do and can keep food on the table . . . for a writer of the theatre in Scotland that is a really privileged position to be in because it wasn’t like that for the first 15 years of my career.”

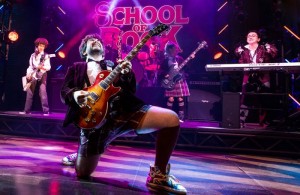

So Billy Elliot is closing after 11 years — and some 4,600 performances in the West End — on April 9, 2016, and no sooner did Andrew Lloyd Webber premiere his latest musical School of Rock in Broadway last Sunday than the very next day he announced it will be coming to the London Palladium next autumn.

I’ve written about the latter here, dubbing Lloyd Webber “the ultimate showman among composers.” The show has marked a significant reversal in Lloyd Webber’s critical fortunes in New York, as I chronicle in the same piece. In the 80s and into the early 90s — Lloyd Webber’s busiest era, creatively speaking, with six major titles opening, from Cats to Sunset Boulevard, with Song & Dance, Starlight Express, The Phantom of the Opera and Aspects of Love in between — the most powerful critic on Broadway was Frank Rich, and it can be safely said he was not a fan.

But even he had to grudgingly admit, in his book Hot Seat which collects the reviews he wrote for the New York Times between 1980 and 1993, exactly the years of Lloyd Webber’s biggest influence — that Cats “was in retrospect the most influential Broadway production of its era, proving that there was a bottomless tourist audience for a show that pushed spectacle over content and that indeed required virtually no knowledge of English to be appreciated, whether by young children or foreign visitors.”

Never mind the idea of spectacle over content; Rich never liked his music, either, declaring in his review of the Song half (Tell Me on a Sunday) in Song & Dance, “As is this composer’s wont, the better songs are reprised so often that one can never be quite sure whether they are here to stay or are simply refusing to leave.”

But last Monday Ben Brantley, now chief theatre critic of the New York Times, gave School of Rock (pictured left) the paper’s biggest vote of confidence in years. As he writes, “Of course, any show that serves up somber preadolescents springing to joyous life via music of their own making is bound to push buttons, especially if the kids don’t seem to be trying too hard. Me, I melted when two little girls started singing the backup chorus from Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” (one of many genial nods to classics). All the children are defined as distinct individuals but without excessive shtick. My personal favorite: the petite, poker-faced Evie Dolan as Katie the bass guitarist.”

But last Monday Ben Brantley, now chief theatre critic of the New York Times, gave School of Rock (pictured left) the paper’s biggest vote of confidence in years. As he writes, “Of course, any show that serves up somber preadolescents springing to joyous life via music of their own making is bound to push buttons, especially if the kids don’t seem to be trying too hard. Me, I melted when two little girls started singing the backup chorus from Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” (one of many genial nods to classics). All the children are defined as distinct individuals but without excessive shtick. My personal favorite: the petite, poker-faced Evie Dolan as Katie the bass guitarist.”

Meanwhile, Billy Elliot – the show that helped Elton John to challenge Lloyd Webber’s crown as King of the British Musical — is closing at the Victoria Palace, to make room for the theatre’s long-planned refurbishment. As it is, the theatre has rather forlornly looked isolated in the middle of the massive building project across the road, so it has been an obstacle course to approach. But Billy Elliot (pictured at the top of this feature) is already set to be embarking on its first UK and Ireland tour in February (both will play concurrently for a while), and I would bet my bottom dollar that that tour will end up back in the West End. Having been streamlined for touring — the original production had to excavate the stage in order to accommodate its set — it would now fit more easily into any available theatre.

Meanwhile, Billy Elliot – the show that helped Elton John to challenge Lloyd Webber’s crown as King of the British Musical — is closing at the Victoria Palace, to make room for the theatre’s long-planned refurbishment. As it is, the theatre has rather forlornly looked isolated in the middle of the massive building project across the road, so it has been an obstacle course to approach. But Billy Elliot (pictured at the top of this feature) is already set to be embarking on its first UK and Ireland tour in February (both will play concurrently for a while), and I would bet my bottom dollar that that tour will end up back in the West End. Having been streamlined for touring — the original production had to excavate the stage in order to accommodate its set — it would now fit more easily into any available theatre.

Still in the musicals corner, the stage version of Bugsy Malone, which re-opened the refurbished Lyric Hammersmith last April, is to return there next June for a 12 week summer season. I wanted to see it again, mainly to enjoy Drew McOnie’s choreography again, during its last run but never got around to it; now I can!

Still in the musicals corner, the stage version of Bugsy Malone, which re-opened the refurbished Lyric Hammersmith last April, is to return there next June for a 12 week summer season. I wanted to see it again, mainly to enjoy Drew McOnie’s choreography again, during its last run but never got around to it; now I can!

And Sunny Afternoon — which is now onto its second West End cast and in its second year at the West End’s Harold Pinter Theatre — has announced it is to launch a UK national tour, kicking of at Manchester Opera House in August.

Finally, the filmed version of the recent Gypsy that starred Imelda Staunton as Momma Rose, is to be broadcast on December 27 on BBC4, as Playbill noticed that the show’s Facebook page had announced. I saw the show four times in the theatre (once at Chichester, and three more at the Savoy); now I can record it and watch it as often as I like!

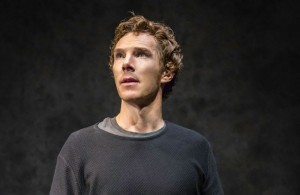

Cumberbatch Hamlet breaks film box office record

The biggest play news of the week was of the breakthrough success of NT Live’s cinema broadcast of the Benedict Cumbatch Hamlet (pictured left) from the Barbican.  According to a report in The Stage, it has taken nearly £$3m at the U.K cinema box office alone — “more than the Michael Fassbender feature film Macbeth – with £2.93 million in takings compared to Macbeth’s £2.82 million. It also broke the record for largest global NT Live audience to date.”

According to a report in The Stage, it has taken nearly £$3m at the U.K cinema box office alone — “more than the Michael Fassbender feature film Macbeth – with £2.93 million in takings compared to Macbeth’s £2.82 million. It also broke the record for largest global NT Live audience to date.”

And The Stage also reveals that, in terms of the secondary ticketing market, it was “was named the seventh most popular ticket for any entertainment or sporting event in 2015. Ticketing website Viagogo revealed the play was more in-demand than the England versus France Six Nations rugby match, though less popular than One Direction’s latest tour.”