The last year of COVID19 restrictions and shutdowns has impacted the entire theatrical community, since theatre was effectively closed to physical business for most of it, and had to migrate (where it could) to an online digital offering instead, which of course isn’t theatre at all but a new hybrid model of video, cinema and television. But at least it provided rare opportunities for employment for actors, creatives and crews.

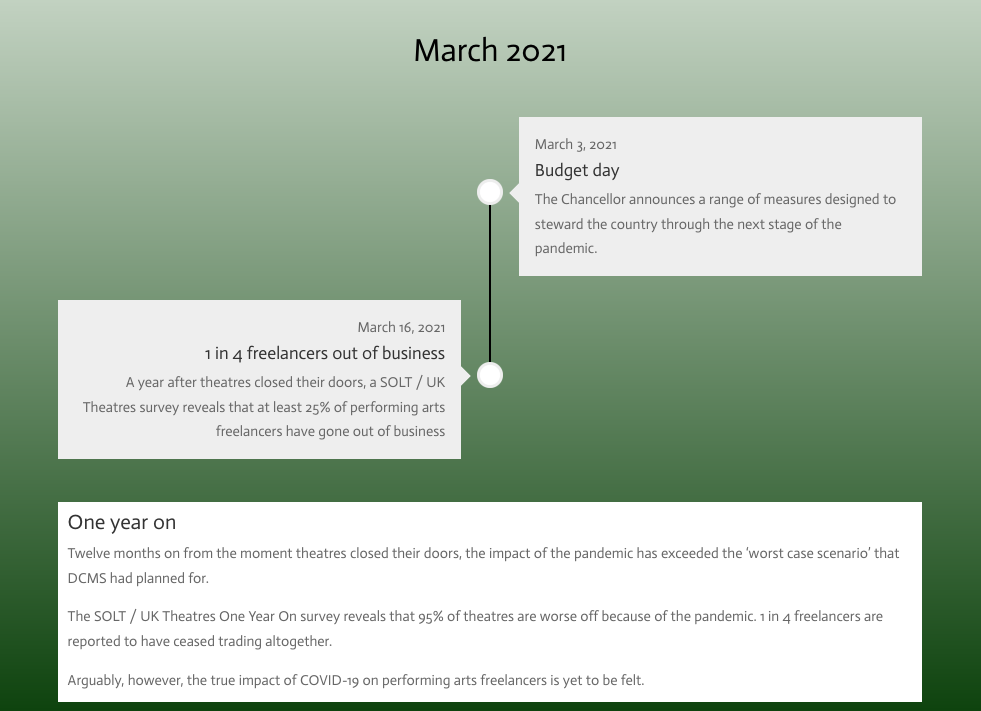

But no one has been more affected than freelancers, who make up the bulk of the workforce and who, according to a new report from Freelancers Make Theatre Work, are responsible for creating 94% of the work created for the nation’s stages. As the report summarises:

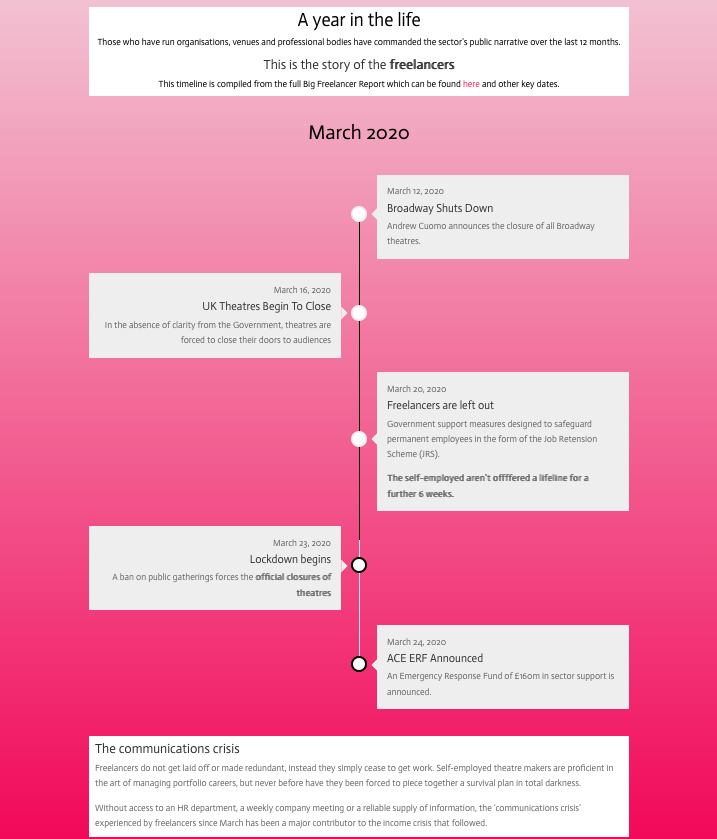

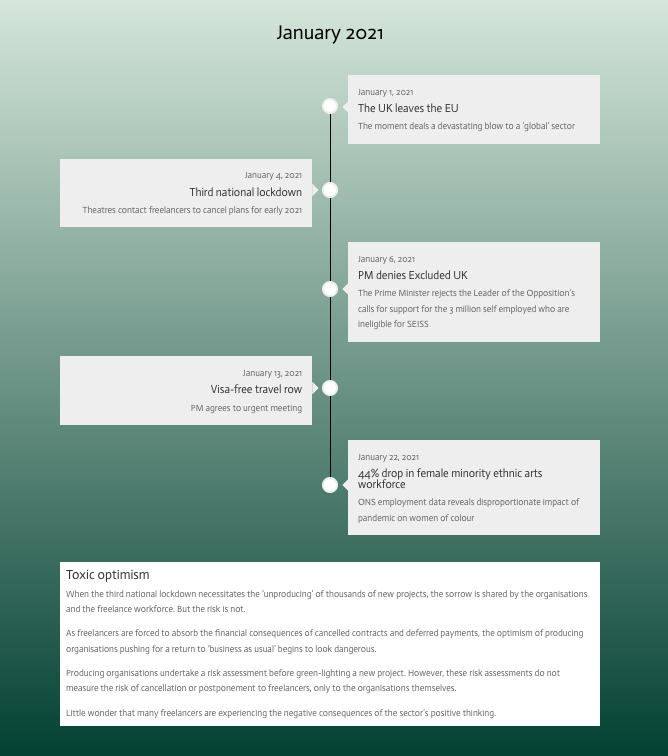

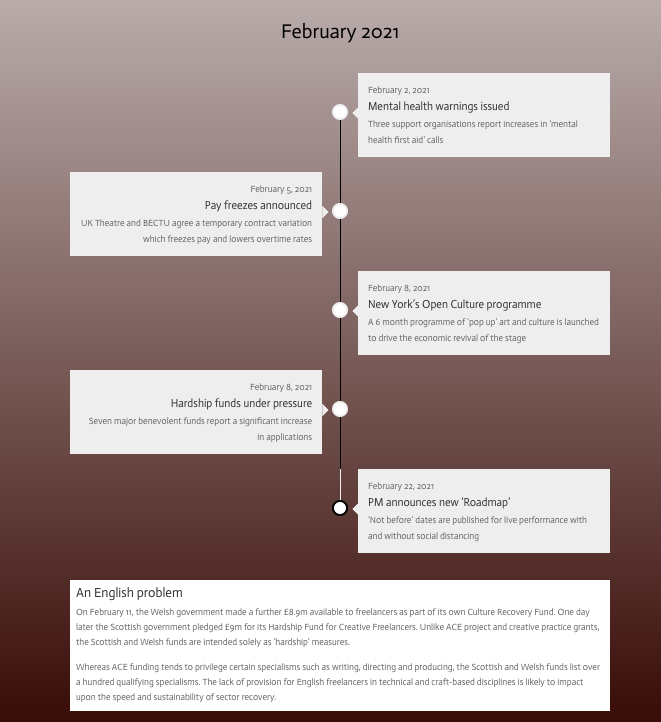

“The COVID-19 pandemic created a situation in which the vast majority the performing arts sector workforce was left with no representation, no access to channels of influence or communication, no direct benefit from the government’s cultural recovery plan, and, in some cases, no income support.

Existing problems of employment status, fair pay, talent development and training, working conditions, and inclusion already place certain burdens on freelance theatre workers. COVID-19 magnified those systemic challenges and added three more: an income emergency, a retention crisis, and a vulnerability regarding safety when returning to the workplace.”

Many theatre workers also found themselves trapped in the no-man’s-land of those that @ExcludedUK was founded to lobby on behalf of: some 3 million people are entirely excluded from the UK government’s Covid-19 financial support schemes. No wonder that so many actors found themselves suddenly transformed into essential workers, working in supermarkets and as delivery drivers, as the only means of supporting themselves.

But the insecurity that lies at the heart of this problem in fact long predates Covid — it was merely exposed by it. As the introduction to the report puts it,

“The COVID-19 pandemic has decimated the workforce of freelance artists, technicians, and craftspeople on whose health and resilience the recovery of the performing arts sector depends.

However, the scale of the crisis for freelancers is rooted in a wider story of inequity which predates the pandemic….

COVID-19 has exposed critical vulnerabilities in this existing business model. For freelancers, these include forced dependency on the sector’s existing infrastructure and organisations, unstable margins of income, significant overheads, and a lack of basic employment protections.

Of significant concern is that the ‘reputational’ aspect of the freelance business model has a coercive effect in the workplace, discouraging individuals to push back against poor pay and conditions, abuses of power, and unsafe working practices. This response was most common in women, and particularly women of colour.”

Recovery money allocated by government was largely allocated to venues, to ensure their survival for when the crisis (eventually) subsidises. As the top dogs of many of them — in particular, executive and artistic directors — kept themselves in employment with those funds, they inevitably furloughed many of their production and support staff; with little or no work being produced on their stages, there wasn’t much for them to do anyway. And the services of freelancers — whether actors or set designers, costumiers and props people — of course weren’t required, either.

As some theatres sought to do more digital engagement, some freelancers were brought back on board, but only on a limited, ad hoc basis, given that the scale of those productions was nothing like they were before. Besides, the costs of simply mothballing the buildings themselves still had to be met, so venues did not have the ability to spend what they would have spent on physical productions on digital ones instead.

But just as #BlackLivesMatter and the #MeToo movement have identified systemic issues of racism and sexism that the theatre world is not immune from, longer-term problems and inequalities have been exposed for the way freelancers are also treated. As the report summarises their position,

“The sector cannot – and must not – return to ‘business as usual’, which to freelancers represents economic exploitation, poor working conditions, a lack of inclusivity, and an inability to shape or determine sector strategy.

Systemic change is required to build a more resilient future and the change most freelancers crave is practical in nature.

However, significant issues must be addressed, including greater employment protections, fair pay, talent development and training, working conditions, inclusion, and the underlying power imbalance and lack of access to sector assets.

The consequence will be an industry better able to reach new audiences, discover new voices, and retake its place at the heart of the nation’s culture.”

I know that as a freelance theatre critic, I’m at the bottom of the food chain of priorities here; but in fact many of the problems identified above apply to me, too, either pre-dating the pandemic or coinciding with it.

For instance, after 18 years as a regular contributor — at one point, filing a daily online column and frequent reviews and interviews, as associate editor and joint chief critic for The Stage — I was released from my established roles with ten days notice in March 2019. (I was, it is true, invited to continue as a ‘regular’ freelance contributor, which entails throwing my hat into the pitching ring for work, which would not have been guaranteed in any way.)

As it is, that Associate editor title was itself more an encumbrance than privilege: on the one hand, it gave me some ‘status’ within the organisation and included a guarantee of a certain amount of features and online columns; but there was no additional money, with no retainer for the title or an enhanced rate for the work that was commissioned.

On the other hand, however, it obligated me to certain responsibilities — including one frequently wielded by the editor that as I was “representing” the publication, I had to be mindful of the impact of my words, even on social media accounts that had no connection whatsoever with the work I did for them. And it also involved countless free hours sitting on judging panels, like the ones for The annual Stage Awards and its Stage 100 list, as well as The Stage Debut Awards; plus regular free consultations with the editor.

In short, I was subject to exactly the same power imbalance that this report identifies for other freelancers within the industry. I had a voice — that is, after all, what I was selling — but I wasn’t always heard; not least when the publication itself turned on me, and published a piece that was heavily critical of another of my endeavours, entirely independent of it, as I previously outlined here. I was effectively told to man up and take it on the chin; that I needed to show how robust I was to criticism.

But the publication’s full-time staff were not given the same message. When, at one point, I publicly pointed out that the news editor had published an incorrect story — as the director of the show concerned had already publicly refuted its facts — he complained to the editor immediately, and it led directly to my dismissal a few days later.

Again, the utter lack of employment protection was also shown with another publication I contributed to for around 10 years, LondonTheatre.co.uk. Just ahead of the pandemic’s arrival, Encore Tickets — who operated the site as part of a portfolio of ticketing sites and white-label ticket selling through other sites — was sold to TodayTix in New York; and obviously with the theatre’s shutdown, there was suddenly nothing more to review.

Editorial supervision of the site was transferred to TodayTix’s New York headquarters, where I approached the editor and was informed that they were suspending freelance editorial while there was nothing to cover, but who assured me she would be in touch once again when things resumed.

When theatre did briefly stage a comeback last September, I contacted her again to pitch some ideas; I was quickly told that the shows I’d mentioned I could cover had already been assigned to other writers. This was the first I heard that she’d decided on a new editorial policy, not concentrated on one “lead critic” (as I used be for the site), but embracing more “new and diverse” voices.

That’s something I can’t argue with — I’ve often called for that myself. But I literally never heard from her again; and it turned out that those “new and diverse” voices included Matt Wolf, who has been a critic even longer than me (including on Variety, the international edition of the New York Times, and currently Broadwayworld.com), and Sam Marlowe, a long-time contributor to The Times.

So yet again my status as freelancer — which gave me freedom to contribute to as many outlets as would have me — also meant that I had no protection or status should they suddenly chose not to have me anymore.

But the story has had a very happy outcome for me, professionally speaking. Since January, I have been working for myself — on this site — and filing a daily column here. And I’ve never felt both more committed and more free. Sure, it puts the free into freelance — I’m currently not being paid anything at all by anyone — but neither am I giving my services away for free, as many sites ask of their critics, in return for those platforms exposing their work there (and securing a free ticket for the show for their efforts).

Nor am I being subjected to the whims of publishers and editors, like in my days at the Sunday Express, where the editor once demanded a five-star review for a show I’d in fact given a one-star review to, mainly because the publicist of that show had once been the Sunday Express’s music editor. I refused to comply; the editor got a staff writer to review it instead, and it didn’t appear on the same page as the rest of the review coverage but on a news page. So my integrity was kept intact; but then the ads started running, which simply said: FIVE STARS — Sunday Express. Which many people naturally thought was me…

Self-publishing is the way of the journalistic future. I own the outlet; the writing; and the editorial process. I choose when to publish.

The next challenge is to monetise it. But I’m happy to do other work to keep food on my table in the meanwhile. And the massive freedom I now have means my husband are planning on relocating to the countryside. I will still have a foothold in London — and will return here for two or three nights a week to catch shows, if and when they return.

So I’m living life on my own terms now, not someone else’s. And it’s truly liberating.