Last weekend was the second anniversary of my last column appearing in the pages of The Stage, as I tweeted here:

No job is for life, of course (not even, it turned out, that of chief theatre critic for The Guardian, where Michael Billington stepped down, aged 78, in 2019, after 48 years in the post). But a large part of my identity, both personal and professional, was wrapped in The Stage, which had provided me with my longest — and by far — most significant editorial home.

No, it wasn’t an exclusive relationship — I couldn’t afford for it to be, given how low its rates are — but I gave it enormous commitment, for a long while filing a daily weekday online column (I was the first such contributor on their website), first under editor Brian Attwood, then his successor Alistair Smith. It evolved into one of those daily columns being re-purposed every week for the print edition as well, before — some 13 years in — being scaled back to three times a week.

I also provided regular features, and — alongside Natasha Tripney — was appointed joint chief critic of the paper: I concentrated on musicals and West End openings, while Tripney concentrated on plays and subsidised theatres. But this was by no means exclusive, and I occasionally reviewed shows at the RSC or regional theatres. I was also given the honorary title Associate Editor (though it came with no pay, it gave me status; but it also, paradoxically, implied a level of control by the paper, as I was seen to be ‘representing’ them).

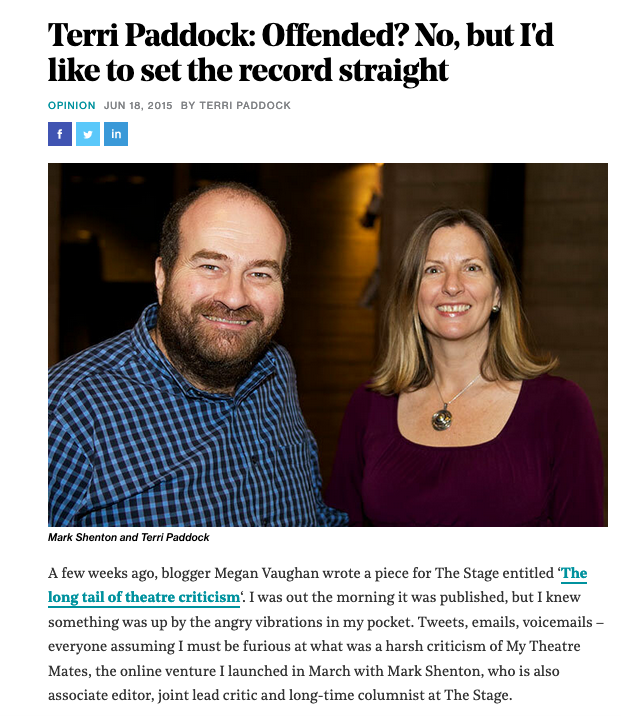

Of course, as with all employment situations, especially freelance ones, there were occasionally tensions: on one (in)famous occasion, the online editor at the time published a piece in The Stage from blogger provocateur Megan Vaughan, after I had co-launched an independent website called MyTheatreMates with Terri Paddock, former editor (and former co-owner) of WhatsOnStage, that he forewarned me would be critical of me, but turned out to be a vicious (and unfounded) assault on the integrity of the site itself. I couldn’t believe that I was being openly attacked by a member of my own team, albeit he didn’t write it, he only commissioned it. But I was told that I needed to be robust enough to withstand such criticism, and it looked good to rise above it.

Terri subsequently wrote an articulate reply (pictured above) that was also published by The Stage here; as she said,

“In Vaughan’s piece, charges levelled at My Theatre Mates – and, really, these must be directed at me, rather than Shenton, as I conceived the site and run it on a day-to-day basis – included suggestions of exploitation and “damaging operational practices”, censorship and being in the pay of publicists. Wow.

But, honestly, I just had to laugh. This was clearly a woman who’d never worked for, let alone started, an online media business. Though well written, Vaughan’s article had the facts about – and certainly the motivations behind – My Theatre Mates so grossly wrong, it was impossible for me to be offended.”

Over the years, naturally, the paper evolved, too. That original online editor departed, and in his stead came two new appointments: a features editor and a reviews editor, both still in post today. Nick Clark, a former arts correspondent of The Independent, assumed the former role, and was a responsive, detailed editor, who often re-wrote copy — but would always submit his changes to me to review and approve before they were published. They were often an improvement on the original, and I was happy to be thus edited.

Meanwhile, my fellow joint chief critic was brought in-house as reviews editor, so she now presided over my work as well as sharing the responsibilities with me for the major reviews, as before. During this time I was also reviewing for LondonTheatre.co.uk, though would naturally file totally different copy for both.

However, once The Stage put its content behind a paywall, there was a tension in the fact that people could access my opinion for free on LondonTheatre, but would have to pay to access it on The Stage; so The Stage asked for exclusivity. I was unable to provide this, given that LondonTheatre paid me more than three times the rate for a standard review there than The Stage did; so I eventually bowed out of reviewing shows that clashed for The Stage. Instead, I assumed the role of chief New York critic, as (in non-pandemic times) I travel regularly to that city, where I also have a (tiny!) home.

But I found myself in increasingly fraught tensions with my reviews editor, who regularly demanded rewrites of most of the reviews I wrote. Small changes were introduced without consultation, and sometimes changed either the meaning or the facts of the review, so I would have to spend time asking for them to be changed again.

When she sometimes requested wholesale changes be made, this would naturally delay publication of the review — on one occasion, I’d offered an exclusive of a review of Disney’s Frozen, on its world premiere in Denver, Colorado, and stayed up late after the opening night to file and submit the review ready for publication in London the next morning, ahead of the game.

However, this was effectively sabotaged when she came back asking for rewrites. Which I duly supplied. (All this, I hasten to add, for the standard fee of £25 for 250 words — and no, I didn’t get a contribution towards travel or hotel expenses while I was in Denver; I was there entirely on my own steam).

Finally — and this was the last straw — I submitted a review for the New York Off-Broadway opening of a double bill of Sea Wall/ A Life, starring Tom Sturridge and Jake Gyllenhaal (pictured above) here; again, rewrites were demanded and promptly supplied. Then the review appeared. And the opening paragraph published was brand-new again, not written by myself at all.

I resigned as New York critic with immediate effect. I had, effectively, been bullied out of the position. I continued to work successfully with the editor and features editor, so I didn’t rock the boat. But I now finally realise how unsupported I was then, and how much my confidence as a critic was serially undermined at the same time.

I know, of course, I am not without fault in the strained relationship that finally tipped matters over the edge, and led to my eventual departure from the publication entirely. It was primarily around small social media storms that kept erupting on theatrical subjects. Obviously my Twitter identity was entirely separate from The Stage — like the rest of the paper’s staff and freelance writers, Twitter wasn’t an “official” channel of our voices, unless it went out from @TheStage’s own twitter handle.

So, when for example, in the summer of 2018, I’d replied to a thread (one I’d not initiated myself) asking for top tips for the Edinburgh Festival with a suggestion that the critics to follow during the festival were Joyce McMillan and Lyn Gardner, I was chastised by The Stage’s editor who said that his Edinburgh reviews team felt affronted by this, because I’d not named them.

Fair enough. They may have seen it as an implied criticism, though none was intended. However, when the reviews editor herself sent her followers to a review of a production that had been published in Exeunt (a publication she co-founded) as the best of any of the reviews that had been written about it, I asked the editor if she would similarly be chastised for not praising The Stage’s own reviewer of the same production, but he claimed there was no equivalence.

I raise these now historical issues again only because it demonstrates that bullying comes in many different forms, and one of them is gaslighting.

It may seem relatively trivial; but such things do matter. As does keeping the record straight.

The last straw that broke the camel’s back was when the news editor tweeted about an ‘exclusive’ that the Open Air Theatre were intending to find a black actor to play Eva Peron in their summer production of Evita; I replied pointing out that Jamie Lloyd, the show’s director, had specifically already publicly denied this was the case.

The news editor complained to the editor, who once again chastised me for apparently undermining his in-house staff; though I was merely pointing out the inaccuracy of this so-called exclusive. Remember how I was told that I needed to be robust enough to stand up to criticism of an initiative I was involved in when The Stage published a column specifically criticising it? Yet The Stage’s news team were clearly not being held to the same robust standard.

The following week I was informed by an e-mail from the editor that I was being stood down as Associate Editor, and my regular columns would cease.