But it’s not all good news on the future for every theatre we’ve already got

London’s theatre stock is ever-improving and ever-expanding, it seems. After a long period of neglect through the eighties, a massive investment has been made in the years since — both to existing buildings, and also in creating brand-new ones.

This has partly been thanks to the lottery, which created a boom time for subsidised houses to improve their homes, like the absolutely brilliant transformation of the Royal Court from a slightly shabby old theatre into a space of deliberately exposed old walls, set against plush new leather seats (still the most inviting of any theatre in London today, pictured above), and major redevelopments of both the National’s home (that saw the Cottesloe transformed into the Dorfman, and new backstage spaces created as well as the riverside bars transformed) and the RSC’s Stratford-upon-Avon HQ.

Other leading London theatres like the Bush (relocated from its above-a-pub original rented home to an entirely repurposed library building around the corner), Almeida and Lyric Hammersmith were also beautifully redeveloped, both in the public spaces and behind-the-scenes (with Hammersmith adding a range of community training and education facilities).

Commercial theatres lagged behind for a time, claiming they could not afford to do the work required on their often ancient homes. But then, thanks to a combination of philanthropy and sheer business sense — that making the theatres themselves better would make them more attractive to producers wishing to rent them, and audiences to visit them — Cameron Mackintosh created what will be his most significant lasting legacy, refurbishing in turn every single theatre as his portfolio expanded; his theatres are now without doubt the most beautiful in London (even if the seating itself is sadly less than generous in terms of comfort, particularly because so many of them are much too close to the floor; a problem if you’re any taller than 5’6).

But thanks to his massive investment in completely overhauling theatres like the Prince Edward (the first theatre he bought), the Prince of Wales, the Gielgud, Sondheim, Wyndham’s, Noel Coward and most recently the Victoria Palace (pictured above), he has created a stock of theatres that is pretty much unrivalled in London.

Lloyd Webber, meanwhile, was slow to catch up on the theatres that he’s owned for even longer; but he’s making amends now. He’s recently unveiled the stunning refurbishment of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane; in an interview published in the New Yorker earlier this week, he took the journalist Anna Russell on a guided tour of what been done with his friend and adviser, Simon Thurley, an architectural historian and the former head of English Heritage, and spoke of his “architectural passion project”.

As she writes,

“The pair had their foreheads scanned and stepped backstage, where they peered up at a towering steel rig. “You could swing several double-decker buses from there,” Thurley said.

The Theatre Royal Drury Lane is the oldest continuously running theatrical site in London. When it opened, in 1663, London had no buses, double-decker or otherwise. It had a lot of fields. People arrived at the theatre mostly by foot, and sat under a cupola that leaked when it rained. When the first theatre burned down, a bigger one, Lane No. 2, was built. When that one was demolished, No. 3 went up; it also burned. (“Theatres are not good things to own, basically,” “Thurley said.) The fourth Lane, the one that still stands, was designed by the architect Benjamin Wyatt. It opened in 1812, with a production of “Hamlet” and a now forgotten musical farce, The Devil to Pay. “The stage is in exactly the same place as it was in the early seventeenth century,” Thurley said.

In 2000, Lloyd Webber purchased the building, which he calls “objectively marvellous.”

They’ve now restored its original Georgian grandeur, at a cost that the article cites as a “£60 million undertaking”. Lloyd Webber described his passion for architecture and especially old buildings:

“It started with a love, when I was a little boy, of really old buildings,” he said, “ruined buildings, like castles and abbeys, and it developed into a love of churches.””Music came along at the same time, “in parallel,” and the Lane unites his interests, “like two worlds colliding.” He and Thurley often visit buildings, he said, that “other people might find a little extreme.” High Victorian. Heavy stuff. “But if you’ve got something like the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, if you’ve got a building like that,” he said, eyes widening, “one’s got the chance to slightly put something back into the buildings.”

This thought gives me no end of pleasure — and anticipation. Years and years ago, I wrote a feature for The Stage which pointed out then-on the sorry state of many of the theatres in his portfolio — and swiftly received a sharp legal letter, suggesting that I’d seriously misrepresented the state of them, and asserting that his company did not take any profits out of the theatres themselves.

One of the things I’d said was that they were in danger of falling down if left untended. Lloyd Webber subsequently disposed of four theatrical houses in his portfolio — the Lyric and Apollo, side-by-side on Shaftesbury Avenue, the Palace (the first theatre he ever owned, further up the Avenue), and the Garrick on Charing Cross Road (held on a long-term lease from the Theatres Trust) to Nimax Theatres.

And soon after he did so, part of one of those theatres DID fall down, namely the roof at the Apollo Theatre, so it turns out I was right! But I also subsequently found out when the sale was reported that the agreed price had been reduced by £1million, to enable the new owners to carry out refurbishments. So now I know why he was so sensitive to my criticisms: they must have affected the sale price.

Anyway, the great thing is that it was a win-win for London’s theatres. Nica Burns has, even without access to the deep personal pockets of Mackintosh or Lloyd Webber, done a great deal for the theatres in her portfolio, which also include the Vaudeville and Duchess, and done extensive refits of them all. Her company is also partnering in creating a new theatre in the new development near the corner of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street, replacing the Astoria, which is yet to be completed.

Then there’s ATG, the entertainment behemoth founded and developed by Howard Panter in the 1990s that grew into Britain’s largest theatre owners, both in London and beyond, with West End venues that include the Duke of York’s (his first theatre), the Pinter (formerly the Comedy), the Lyceum, the Savoy, Piccadilly, Phoenix, Playhouse, the Apollo Victoria and Fortune.

Since the group was sold, with venture capital backing, to new owners, and led to the departure of Panter and his wife Rosemary Squire, that portfolio has been augmented with the Ambassadors (snatched from under the nose of Cameron Mackintosh, who thought he was buying it but had not completed the agreement on with its former owner Stephen Whaley-Cohen); while ATG have also continued to expand into foreign territories, particularly in America, where they now also own two prominent Broadway houses (the Lyric and Hudson, and other theatres outside of Manhattan).

In Panter and Squire’s parting agreement from their former company, they retained ownership of the former Whitehall Theatre, that Panter had overseen what I have always regarded as the misguided transformation of into the Trafalgar Studios, comprising a seriously vertiginous main house with the most cramped and uncomfortable seating in all of London (pictured above), and a claustrophobic downstairs studio space.

However, they have now rebranded it as the Trafalgar Theatre, and reinstated it to its former Whitehall Theatre art deco glory days, after the (thankfully temporary) vandalism of the Trafalgar Studios. And though it is currently the only West End theatre in Panter and Squire’s new Trafalgar Entertainment group, they are also on another global expansion mission.

A few months ago they acquired and incorporated HQ’s regional theatre venues into the group; they’ve also acquired the lease to operate a refurbished theatre in Sydney, Australia; and yesterday it was announced that they’ve also acquired the lease on a brand-new venue that is under construction at Olympia in west London that is part of a £1.3 billion Olympia redevelopment project. It will create a new cultural hub in west London; in addition to the state-of-the-art 1,575 seat new theatre (scheduled for completion in mid to late 2025), there will also be a four-screen arthouse cinema, restaurants, shops, cafés and 550,000 sq ft of office and co-working space.

The theatre is reported to be the largest new permanent theatre build of its kind to open in London since the National Theatre in 1976. It is being designed by Haworth Tompkins, the UK’s go-to theatre architects — their other work has included the aforementioned Royal Court, the NT’s transformation, the brand-new Bridge Theatre, the redevelopments of the Young Vic and Battersea Arts Centre, the Bush’s new home, the Open Air Theatre in Regent’s Park, Chichester Festival Theatre, Bristol Old Vic, the Liverpool Everyman, and Theatr Clwyd’s future planned redevelopment in 2023.

So even though British theatre, as with the rest of the world outside of Korea, has had a terrible year and a half, the future is looking brighter already. New openings — like the new theatres at Tottenham Court Road and Olympia — inspire serious new hope. On a smaller scale, the Windmill, off Shaftesbury Avenue, is also due to be returned to use for live performance, with a licence for a 250-seat auditorium recently by Westminster City Council; plus a second basement space for 100.

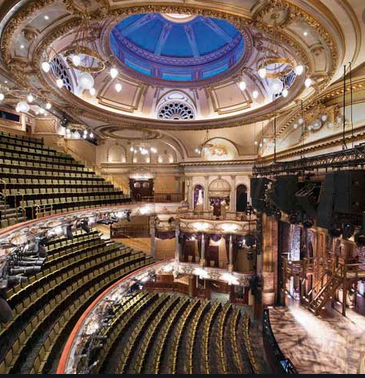

On the other hand, also in Soho, the stunning new Boulevard Theatre — pictured above, which only opened in October 2019, but had been shut down by the arrival of Covid in March 2020 — is unlikely to re-open as a producing theatre. Former artistic director Rachel Edwards — made redundant with the rest of the staff — told The Stage this March that it is “safe to say it won’t be reopening as a [producing] theatre anytime soon”.

Founder Fawn James, from Soho Estates, commented on the theatre’s website,

“The Boulevard was in its infancy as a company, which brings about its own challenges, but coupled with the uncertainty surrounding when theatres can re-open to full capacity and the difficulty in viably operating a small venue in a Covid-secure manner, we are left with no choice but to remain closed…. It has been such an incredible journey launching the Boulevard with my artistic director Rachel Edwards and the wonderful production and hospitality team that made the Boulevard what it was. I will be forever grateful for the tireless efforts that everyone put in to sharing in and creating my dream of re-opening the Boulevard and for the exciting inaugural season that we had ahead of us. We had such exciting prospects, which have sadly been taken away from us by causes out of our control.”

In The Stage she also further amplifies that Soho Estates is

“a real estate company, so when the pandemic hit, it became apparent very quickly that its wider business would be battered by Covid. The Boulevard really was a passion project. The company already knew it would make a loss – it didn’t make much economical sense in the best of times when it could underwrite the venue, but when Covid hit it could not afford to carry on as its wider business was suffering so much. At the moment it’s not viable to underwrite it. Unless funded generously by Soho Estates, it can’t exist as a commercial producing house – it does not make economic sense.”

She does hope to bring it back in some form. It is not the only theatre whose future may be in jeopardy: the Menier Chocolate Factory, where all performances were suspended soon after previews had begun for its British premiere of Paula Vogel’s Broadway play Indecent, is yet to make an announcement about its return. It did receive a great from the Cultural Recovery Fund, stating on its website, “As a non-subsidised venue, we have been particularly badly hit by the impact of the pandemic — this generous grant from the Cultural Recovery Fund is, quite literally, a life line, and one we are hugely grateful for.”

And yesterday it was revealed that Andrew Lloyd Webber is selling The Other Palace, formerly the St James, that he acquired in 2015, and which he’d intended to position as a home for the development of new musicals. In a press statement he said,

“The Other Palace is a wonderful and unique place. It has a theatre, a separate studio space and an excellent restaurant that shot straight into the Michelin and Good Food Guide within a couple of months of opening. It’s the perfect place to produce new work and showcase live performances. I have hugely enjoyed owning this amazing creative facility and it is heart wrenching to put it up for sale. I hope the future owners will love it as much as I have.”

The theatre stands on the site of the former Westminster Theatre, and was incorporated into the development of new flats that sit above it — no doubt a requirement of the planning application to demolish the Westminster and build them in the first place. But now that even Lloyd Webber’s deep pockets couldn’t make it commercially viable, I wonder what the future will hold for it? It lacks the seating capacity to make big returns even if a show is a hit there. Could it end up, like the Mermaid Theatre next to Blackfriars station, as another conference facility?

Even as many theatres start opening up again next week, there are others that look like they’re being left behind; let’s hope we’ll see them come back to life soon, too.