Back in 2005, when Clint Dyer directed The Big Life that transferred from Stratford East to the West End’s Apollo Theatre, he became the first black British director to have a musical on there, he told me in an interview at the time,

“The wonderful thing about being black in this country is that you have an amazing opportunity to be the first at a lot of things.”

In a letter to The Stage two years ago, Philip Hedley (who was artistic director of Stratford East at the time the show was programmed), wrote,

“However, despite the stream of excitedly favourable reviews he received for his direction 14 years ago, Dyer remains not only the first but also the only black British director to achieve such a breakthrough. With his very first production, Dyer hammered a crack into that particularly tough glass ceiling, but it isn’t quite shattered yet, it seems.”

However, Dyer went on to shatter another glass ceiling when he became the only black British artist to have worked as an actor, writer and director on full-scaled productions at the National Theatre; and last week, yet another trailblazing accomplishment was added when he was appointed deputy artistic director to Rufus Norris at the National Theatre.

In a press statement, Norris commented,

“Over the last few years, we have been working with a greater number and range of theatre-makers than at any other time in the NT’s story; as well as making his own work, Clint will play a vital role in supporting these artists to create world-leading theatre for the NT’s stages and beyond.”

Of course, there’s only ever one person who can first at anything, and it is remarkable indeed that Dyer has repeatedly managed to be that person. But we should also ask why he repeatedly has to breach these barriers at all: why haven’t they fallen before he got there?

——————————————————————————————————–

From Stratford East to the British Library

It was reported this week that the the archive that actor-turned-archivist Murray Melvin has been diligently assembling at the Theatre Royal Stratford East has been donated to the British Library. I first met him in 2006, when I had the joy of interviewing the late Victor Spinetti — a fellow veteran of Joan Littlewood’s company that put this theatre on the map in the 50s and 60s — in a public platform performance at the National Theatre; Murray was in attendance, and has long been a fund of stories of his own about the Littlewood years and beyond.

As he tells Michael Billington in The Guardian,

“Joan was also never a favourite of the Arts Council, who said they wanted her to have a board of directors and a three-year plan. Her response was, ‘Three-year plan? I don’t know what I’m doing next week until the postman arrives’.”

Both Brendan Behan’s The Quare Fellow and Shelagh Delaney’s modern classic A Taste of Honey (in which Murray himself Geoffrey, the gay art student) were scripts that turned up in the mail.

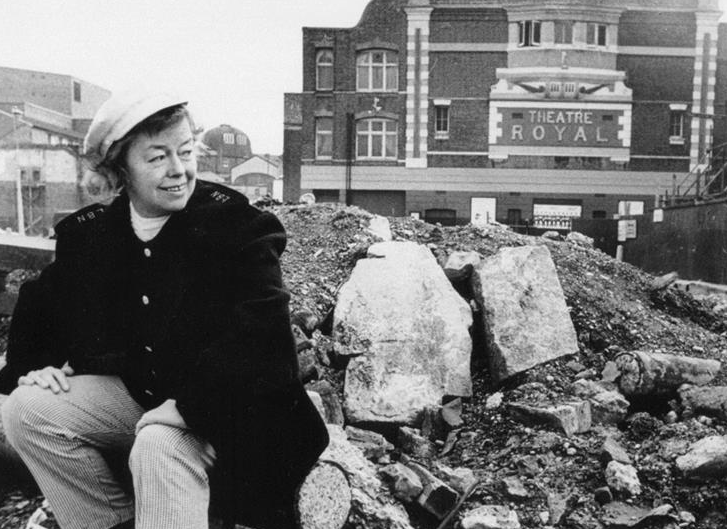

Murray also speaks of how influential Littlewood (pictured above outside the theatre) was:

“She changed the face of British theatre – quite literally. She not only did away with box-sets but Max Factor makeup: John Bury, her designer, introduced side-lighting from Germany which meant that actors didn’t have to appear caked in greasepaint. She also said that she didn’t want to catch anybody ‘acting’: ‘if you’re going to do that acting,’ she’d say, ‘you’d better go up west.’ What she meant was that ‘acting’ was external whereas the performer had to create the situation through their own internal impulse…. It was once said that Theatre Workshop was the Trojan horse that brought modern theatre into Britain.”

———————————————————————————-

Stepping Up to Involve the Community

One of the signature achievements of Stratford East has always been how embedded it feels in its community. As Georgina Brown wrote in The Independent back in 1993,

“The audiences often get better reviews than the plays. It’s excitable, uninhibited and out to party – a very distant relation of the cool, collected and polite customers in the West End.”

And Philip Hedley, a protege of Littlewood’s who inherited her mantle, very much epitomised her ideals, telling Brown in the same piece,

“Theatre exists in its relationship between audience and stage, and different groups within a single audience respond differently at different times. The more mixed the audience in terms of age, race and class, the greater the resonance a piece of theatre can have. That has to be the ultimate goal.”

That aspiration has, of course, been more widely adopted in theatres up and down the land since, onstage and off.

Talking of which, I’m feeling a little chastened: just under a month ago, I contrasted the busy activities that had come to my attention of the Old Vic in the Cut, while the younger (though no longer quite so young) Young Vic down the street, I wrote here, “has been largely inert; it briefly and for one early October weekend sprang back into life to celebrate its own 50th anniversary with a series of readings of newly commissioned work presented under the umbrella title The New Tomorrow” (and for which Kwame Kwei-Armah Jr was the event DJ).

But I’ve just caught up, belatedly, with Lyn Gardner’s column for The Stage from last week, about Twenty Twenty, a project that’s been running there which she described thus: “The year-long initiative is made with professional artists and local participants and aims to create an in-depth, ongoing creative relationship with people in the local community and three on-the-ground community organisations based close to the Young Vic.”

According to Gardner’s column, the initial spur was a report published by the Office for National Statistics in 2019 that “found the Young Vic’s closest boroughs, Southwark and Lambeth, registered in the bottom 10% for well-being in the UK. For many residents, loneliness was a major blight, something many more have experienced during lockdowns. The participants have been drawn from Thames Reach, a charity committed to ending street homelessness, Certitude, which supports those with learning difficulties, and the Blackfriars Settlement, which works with those who have complex needs. Each of the three organisations has been paired with a writer-director partnership.”

Twenty Twenty, says Gardner, marks a shift in focus “to a more long-term and embedded way of creating and delivering participatory projects. The shift comes with increased recognition that the benefits for a theatre working this way lie not in the offer it makes, but in understanding it can learn from the community organisations working in its local area and those who take part in the projects.”

So the Young Vic has been beavering away in connecting with local people. And as Lyn pointed out in another follow-up column in The Stage this week,

“Sometimes even theatres that are fully committed to such practice don’t sing about it on their websites. You have to poke around to find it. I wrote about Twenty Twenty because I received an email about it, and I thought it sounded great. But the email arrived because the Young Vic has a well-resourced press department. Dozens of projects across the country don’t have the resources to send arts journalists information in case we write something about them. Which we probably won’t if Benedict Cumberbatch is starring elsewhere the same week.”

Ouch. But very true of the priorities of national newspapers, where big names mean big column inches.

Meanwhile, less heralded work that burrows deeper into its own community (which also happens to be mine, as I live about 15 minutes walk from the Young Vic) passes far below the radar.

I’ve been strangely more aware of the community work being done at Theatr Clwyd, hundreds of miles from where I live, than the Young Vic, and that’s precisely because publications like The Stage have shouted about it, awarding them this year’s Stage award for regional theatre of the year.

As Clwyd’s executive director Liam Evans-Ford and artistic director Tamara Harvey commented in their acceptance speech for the award, “It’s been a deeply challenging year across the sector. At a time when we’ve not been able to sell tickets or tell stories on our stages, we have tried to use our skills to help people in our local community and our wider artistic community.”

And Harvey provided just one inspiring example of that back in June, when she spoke to a local paper called The Leader, and provided proof of exactly what leadership means. She was asked what what her best moment working at the theatre has been, and it turned out to be one that occurred that day:

“This morning. Walking into the building past the long grasses and weeds growing up around it, I felt such despair at its closure. Then, as I walked up the stairs, I heard music coming from the Anthony Hopkins Theatre. I crept into the back of the auditorium and on stage was George – a local boy who got a place to study with the Royal Ballet in September but had nowhere to practise during lockdown, so asked to use our empty stage. As I stood there watching him dance, I thought maybe we’re going to be ok. Because even in the midst of chaos and uncertainty, creativity still finds a way – there is still music in the empty theatre. We are still finding a way to serve our community and we will keep finding a way to bring people up our hill to share stories, and to laugh, cry and dream together.”