The case that Seyi Omooba [pictured below] brought before the Central London Employment Tribunal against Leicester’s Curve Theatre and her former agents Global Artists for respectively dismissing her from the starring role of Celie in a 2019 production of The Color Purple and from their books representing her concluded on Monday, bringing to a close what The Stage called “one of the most significant theatre-related hearings in recent times.”

She had originally sought £128,000 in compensation, but reduced it to £71,400 ahead of the final day’s hearing: as The Stage reported, “Part of this is an acknowledgment of the impact that Covid-19 would have had on her potential earnings, but she has also abandoned a claim for £4,309, the amount of her agreed fee for the musical.”

Last week Curve’s chief executive Chris Stafford had told the tribunal that they’d offered to pay her full agreed fee — but she’d failed to invoice them, despite chasing her several times.

The Daily Mail detailed how Tom Coghlin QC, representing Curve, said at the tribunal: “The offer remains open, it’s still there but you’ve not engaged at all. Instead you’ve chosen to bring a breach of contract claim. It’s to misuse a tribunal procedure, isn’t it, to bring a claim for money that’s always been offered to you?”

Omooba replied: “No, because you, they, wanted to get away from the situation. In my mind, you just wanted to get away from it. You just wanted to give me money knowing full well they fired me based on my beliefs and they didn’t want to handle the situation. That’s why I didn’t give them an invoice.”

No wonder she withdrew that part of her claim as the basis for requesting it collapsed. It was not the only part of the case that was exposed as entirely groundless. As I previously reported here last Wednesday, in a piece on playing out conflicts between actors’ private lives and beliefs in public, she had previously made clear to her agents that she would not play a gay role, and claimed that in the production she had never been asked “explicitly to play this character as a lesbian,” according to her lawyer Pavel Stroilov

He argued that in the Steven Spielberg film version of Alice Walker’s novel that the musical is also based on, “the lesbian theme is not present at all, there is one kiss between the female characters which can be interpreted in all sorts of ways. It is in no way obvious and was never made clear to claimant that she was expected to play a lesbian character.”

Except, of course, she was not auditioning for a stage version of the film, but a newer stage musical version of the book, which is readily available to buy at bookshops (or on Amazon). Or, as I pointed out then, she could have just read the reviews of the musical version’s 2013 premiere at the Menier Chocolate Factory, which a quick google search would have revealed.

As Curve’s barrister Tom Coghlin put it, “The role that she complains about being dismissed from is one that she would have refused to play in any event. Her choice was to resign or be dismissed and she chose to be dismissed.” Her stance, he said, constituted a “repudiatory breach of contract” and that her dismissal was therefore not “unwanted conduct”.

But in fact it was also disclosed at the tribunal that no such research would have been required for her, as she’d ALREADY appeared in a production of the show herself, playing a different role (Nettie, Celie’s sister) in a concert version presented by the British Theatre Academy at London’s Cadogan Hall in 2017.

Christopher Milsom QC, representing Global Artists, had asked her how she could have performed as part of a production in which the character of Celie kisses another female character on stage, and not recognise the lesbian theme of the story. According to a report of this part of the proceedings in The Stage, published on February 3, “Omooba initially replied that she was not on stage at the time of the kiss, but later said she was ‘at the side but wasn’t watching the whole time’ and did not remember a kiss. This was after Milsom said he had spoken to several members of the concert’s creative team who claimed that Omooba did not leave the stage during the performance.”

So another plank of her defence was comprehensively demolished. And when Curve’s barrister Tom Coghlin QC asked her about the relationship she was being asked to portray being in the script all along, she claimed she had not read it before accepting the role, though she had now, telling the tribunal: “In rereading it now it was evident that there was some lesbian attraction there, and I didn’t reread the script when taking the role.”

To which Coghlin replied, “Whether or not you find a different way of rationalising it, it is obvious, if you know this script from rehearsals, if you know the book, it is obvious that there is a real likelihood that this would be interpreted by many people in the theatre that this is a lesbian relationship.” Omooba, however, refuted this: “No. If it was I wouldn’t have been able to play it.”

Having failed to do this much basic due diligence on a role she has agreed to play, how did she know whether or not the role compromised any other of her fervently-held values and beliefs? It’s a potential minefield.

But because, as she admitted clearly above, that she would have refused to play the role as written, the theatre were forced to dismiss her; as Chris Stafford suggested to the tribunal, if it had not done so they would have been forced to cancel the show. As The Stage reported,

“Curve is arguing that both the commercial and artistic success and integrity of the production would have been jeopardised by Omooba’s continuation in the show, in addition to damaging Curve and co-producer Birmingham Hippodrome’s reputation, risking the departure of other members of cast and crew, and hurting the standing of The Color Purple as an LGBT+ work of art.”

According to Stafford, “I do not believe that the criticism would have gone away. Actually I think it would just have increased and become more intense [which] would have had a major impact on our ability to be able to present the show as intended. I would have been left with no other choice but to cancel the production. To get to the stage of rehearsals and then for the lead actor to say she wouldn’t play a lesbian, our theatre’s credibility would be shot, the rights holders at that point would be advising not to go ahead. We would have had to draw a line under the production and cancel The Color Purple.”

Referring to Theatrical Rights Worldwide, who control the rights to the show, he said they could have withdrawn their agreement for Curve to present the show, as losing the lesbian storyline “would be in massive contrast to how the authors intended” it to be presented. He also said the theatre “would surely have had boycotts”, which would have proved a “commercial nightmare”.

Her former agents feared the same thing, with Michael Garrett — owner of Global Artists — telling the tribunal that they feared an exodus of other clients:”I was concerned that the enormous offence caused [among] the community would lead to an exit of a number of clients and staff. That would have had a commercial, financial impact on the business.” He also feared that two of his agents would leave, too. As The Stage reported,

In addition, the company had to take into account the likelihood of Omooba finding further work, Garrett said, in order for its relationship with her to be successful. ‘My decision was that it was extremely unlikely,’ he added.

And there’s the final, tragic nub of it: regardless of whether she succeeds in her claim against Curve and her former agents, her career is ruined anyway at this point. One in which, her lawyers claimed, she’s the victim, not the cause. According to The Stage,

On the hearing’s final day, Omooba’s representative Pavel Stroilov accused both Curve and Global of inflicting “life-changing” actions on Omooba and ending her career “abruptly and unfairly”.

“These two respondents were in effect the gatekeepers of the industry for her, at that moment, [the] people who had the actual working relationship with her at that time. They closed the gate,” he said.

To which Curve’s barrister Coghlin replied, “As for the life-changing decision, this was from a role that she didn’t want and would have refused to play.” And Global Artists’ barrister Christoher Milsom dubbed her “the author of her own misfortune”, and said the impact of her comments on her employability made her contract with the agency “an empty vessel”.

As we now await the tribunal’s judgement, this unhappy case has revealed a deep fault line between an actor’s viability and her religious beliefs. But given those conflicts, it is clearly her own responsibility to avoid work that conflicts with those publicly-expressed sentiments.

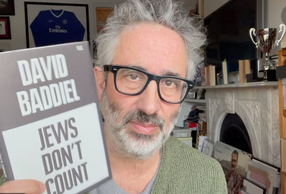

In separate but related news, David Baddiel’s polemic Jews Don’t Count has been published this week, and as Dominic Lawson’s review in the Sunday Times puts it, “is one angry book. To make it spicier still, the anger is directed entirely at what the author sees as his own political home, or as he puts it: “This book is about progressives.”

As The Spectator‘s Nick Cohen amplifies, “His central and unanswerable contention is that, in a time of identity politics, when every persecuted minority is listened to, there is one ethnic minority large numbers of progressives do not want to hear from: Jews, one of the most persecuted minorities in history.”

Baddiel cites the case of Alice Walker — who happened to have written The Color Purple, whose source material was, of course, the bone of contention in the case described above.

In 2017, she wrote a poem called ‘To Study the Talmud’:

“Are Goyim (us) meant to be slaves of Jews, and not only

That, but to enjoy it?

Are three year old (and a day) girls eligible for marriage and intercourse?

Are young boys fair game for rape?

As Cohen goes on to say, “It was grotesque. But the idea that an African-American author could ever be cancelled for racism against Jews remains unthinkable to right-thinking people, even though Walker went on to endorse the works of David Icke, whose anti-vax lies could incidentally lead to the deaths of, among others, a disproportionately high number of black people suffering from Covid-19. In 2019, a musical version of the Color Purple came to the UK. There was a hell of a fuss because Seyi Omooba, one of the cast, had once written an anti-gay post. The producers fired her, of course. Omooba’s prejudice was unforgivable, while Walker’s was, if not quite forgivable, then a matter of no consequence.”

Baddiel’s conclusion is: “Omooba got cancelled. Alice Walker — no one ever even suggested she should be. And, of course, The Color Purple musical went ahead.” (Though not, of course, with Omooba, about whom the fuss was made; but there’s clearly a separate case to be made against Walker’s own anti-semitism).

And in the muddy waters that this cultural war is being fought in, other issues have arisen. As Lawson again, in the Sunday Times review, states:

“As far as showbusiness is concerned the debate has taken a new turn. As Baddiel points out, there is now a view, most noticeably expressed by the dramatist Russell T Davies, that only gay actors should be permitted to play the role of gay people. And we have long passed the time when white actors could, by blacking up, play figures such as Othello. So why, Baddiel asks, do none of the “progressives” think that only Jews should play Jewish figures? He cites Gary Oldman playing the central role of Herman Mankiewicz, the screenwriter of Citizen Kane, in the film Mank, using Yiddish phrases at various points, as the drama demands. This is the Oldman who defended Mel Gibson, after the latter’s openly antisemitic rant, saying those offended by Gibson should “get over it”.

The point is not whether it is right that only those from a particular minority group should be allowed to play figures from that background, but that those who take this line don’t think it applies to Jews. Or, as the book’s title puts it: Jews don’t count. To the counter-argument that Jews have done very well in Hollywood, Baddiel points out that for decades Jewish actors had to change their surnames to get anywhere (so Izzy Danielovitch became Kirk Douglas). To be blunt, they had to pass as Gentiles to play Gentiles.”

Baddiel compares anti-Jewish prejudice with racism based on colour, and points to attacks on synagogues. This, he says, “is why Jews don’t feel white, if by white you mean safe. And as for me: I didn’t feel white when, as a twelve-year-old at a new school, a teacher was overheard to say of me, venomously, ‘Jew’ . . . I didn’t feel white when a man behind me at Stamford Bridge shouted repeatedly ‘Fuck the fucking Jews’ . . . and, as the examples of Jews not counting have built up, I haven’t felt all that white writing this book.”

For his part, Lawson concludes:

“I think there is something fundamentally different for those who experience colour-based prejudice. Changing their surname does not enable them to “pass”. But I was brought up short when Baddiel mentioned a Jewish woman he met who had had a ‘nose job’ because she felt its original shape gave away her origins, and that by ‘de-Jewing’ it, she would be less, well, identifiable. My mother had the same cosmetic surgery. And now I wonder: was it for the same reason?”

My own mother [pictured above] did exactly the same thing when I was a child. At the time, I (and her husband, my father) were led to believe that it was purely cosmetic. But about twenty years ago, I discovered that her mother was Jewish (who had married out of the faith in pre-Nazi occupied Poland, knowing what was coming), and although my mother was raised a Catholic (her father’s religion), she had definitely sought to disguise a key physical marker of her origins. It was, by all accounts, successful. My father did not question her reasons for the nose job. And it was only after her death two years ago that he actually found out the truth about his wife, something my brother and I had known for a lot longer.