I came out of a matinee today at the Vaudeville to find that bus routes to take me from the Strand back across the river had been suspended: there was a fire in Holborn (see inset), viagra approved and none were operating . After a few minutes, a bus arrived that was going as far as Waterloo — so I jumped on board that to get me part of the way. On the other side of Waterloo Bridge, it got held up in traffic — just as the northbound lanes of the bridge were being shut off.

. After a few minutes, a bus arrived that was going as far as Waterloo — so I jumped on board that to get me part of the way. On the other side of Waterloo Bridge, it got held up in traffic — just as the northbound lanes of the bridge were being shut off.

Oops. It looked like a controlled kind of chaos was about to hit the West End. And as ever, it seemed that Twitter was providing (some of) the answers. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory tweeted, “Due to incident at Holborn, tonight’s 7.30pm performance of @CharlieChoc_UK has been CANCELLED.” On The Lion King’s website, they posted this update at 16:22: “Due to circumstances beyond our control, we have been left with no option than to cancel this evening’s performance.”

I was due to return to town tonight to catch the Royal Opera’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. I checked the Opera House website where it told me, “The scheduled Royal Opera performance of Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny on 1 April 2015 will go ahead, although due to some loss of power at Holborn, we are unable to provide any bar or restaurant services tonight.”

Its curious how Drury Lane has “no option” to cancel whereas the Opera House, just a minute away, seems to be able to go ahead, albeit without catering. But then perhaps its less surprising when you realise that the Opera House is tonight broadcasting its performance live to cinemas around the UK…..

Best twitter update has to go to The Play That Goes Wrong, across the street from Drury Lane: “It may seem like an April Fool’s joke (and you know what we’re like!), but tonight’s performance is most definitely cancelled #sorry”

But I’m confused why the Society of London Theatres — the member organisation who, after all, should be best place to provided exactly this kind of information in a co-ordinated way — isn’t doing so, with their website merely reporting at 4.55pm, “A number of theatres have been affected by the electrical fire in Holborn and the surrounding areas. The current advice for anyone with tickets for a performance tonight in the West End is to call the box office directly.”

** NOTE: THIS SPEECH WAS GIVEN AS PART OF THE YOUNG CRITICS’ PROGRAMME HELD AT WINCHESTER’S THEATRE ROYAL ON APRIL 4, pharmacy 2015 **

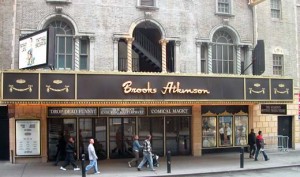

No one ever built a statue to a critic, click it was once famously said, but in 2013 two critics received OBE’s in the Queen’s New Year’s Honours list. Michael Billington and Philip French, theatre and film critics for The Guardian and The Observer,were honoured after writing reviews in their particular disciplines for a 100 years between them. And in New York, there are not one but two Broadway theatres named after critics, Brooks Atkinson (pictured left) and Walter Kerr. We don’t yet have a Ken Tynan or even a Jack Tinker Theatre here, let alone a Billington.

(pictured left) and Walter Kerr. We don’t yet have a Ken Tynan or even a Jack Tinker Theatre here, let alone a Billington.

And 2013 marked another centenary: that of the Critics’ Circle itself. So critics have been around for a long time, and are still having a demonstrable influence in setting the cultural agendas of the areas they cover. But will they be around much longer?

Some years ago, I wrote a feature that was titled What’s the Point of Critics, and I quoted some of my colleagues’ reactions to the Queen musical We Will Rock You, as well as my own. “Only hard-core Queen fans can save it from an early bath,” wrote my then Daily Express colleague Robert Gore-Langton, and I myself called it a “grim spectacle” and “tacky, trashy tosh” in the Sunday Express.

Those were some of the kinder comments. The Daily Telegraph’s Charles Spencer thought that far from being guaranteed to blow your mind, it was instead “guaranteed to bore you rigid”, concluding “The show is prole-feed at its worst”.

There are either more hard-core Queen fans than the Daily Express expected, or it’s reaching a wider demographic of what the Telegraph dismissively called ‘proles’, because it ran for over a decade at one of London’s largest theatres and also won a special Audience Award at the 2011 Olivier Awards in a public vote for people’s favourite show.

Is this a rebuke to the so-called power of the critics? And just as importantly, how are critics being affected by the changing fortunes of the outlets where they write? Not only are the traditional distribution channels of the print media changing, but the online world is also one in which blogs, bulletin boards, chatrooms and Twitter are offering far more outlets for opinion. Everyone has an opinion, of course; but what what they now have, too, is the means to broadcast and publish it, whether in the form of a 140-character tweet or contributing to one of the numerous theatre websites. It means that everyone, now, is a critic. Or at least, has a voice.

The result is that far from being the ultimate word on a production, critics are only the start of a conversation around it, not the end of it. That’s something I personally welcome: it means that the conversations that critics are part of are now richer, as critics have also had to become more engaged with both those they write for and those they write about than ever before.

But it also means that there’s a lot of noise to filter before readers get down to the authority of people actually appointed (rather than self-appointed) for their expertise and knowledge. And amid all the noise of the internet, authoritative voices are even more important than before, not less. But establishing one of those doesn’t require the backing of a professional media organisation anymore; the ability set up and manage a blog may be all that is necessary, as the West End Whingers proved over here, with a catchy name and an even more catchy turn of phrase that gave them international notoriety when they dubbed Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Love Never Dies as Paint Never Dries.

My colleague Terri Paddock, founder and former editorial director of Whatsonstage, and I have recently set up a new initiative called My Theatre Mates , whose aim is to consolidate and aggregate the power of independent theatre journalists by bringing our separate blogs under one distribution banner. We still have our independent sites, but we now have a way for the public to find us in one place.

, whose aim is to consolidate and aggregate the power of independent theatre journalists by bringing our separate blogs under one distribution banner. We still have our independent sites, but we now have a way for the public to find us in one place.

The best writing about the theatre isn’t necessarily happening in the mainstream media anymore either. In 2010, he academic and writer Jill Dolan won the George Jean Nathan Award, America’s biggest theatre criticism award, for her blog The Feminist Spectator.

Writing in a Guardian blog, Karen Fricker – a fellow academic and part-time critic – noted at the time, “One can’t also help but feel a pragmatism in the committee’s decision – opening up to bloggers means that they’ll continue to have people to give the award to.” George Hunka, another American theatre critic turned blogger, also noted of Dolan’s award, “Anyone with access to the web can be a critic these days, but fewer and fewer people can actually make a living at it. Dolan, presumably, doesn’t get paid a dime for her blog, but has her academic income to support her.”

Real, experienced critics matter more, not less, in this new world. But where do you find them? My Theatre Mates is one place to start. There’s no question that the landscape of journalism is changing forever, and the models have changed faster in the last 20 years than the previous 200.

The Edinburgh Fringe provides a nearly perfect working model of what the future may look like. Just as the fringe provides the ultimate form of democracy, where there are no barriers to entry and anyone can put on a show, so anyone and everyone can review them, too.

But, actually, out of that cacophony of voices out there, the critic who not only has something to say but is also listened to is more important than ever. Amid the welter of unknown by-lines, Lyn Gardner  (pictured left) in The Guardian demonstrates a tenacity and dedication in seeking out the most interesting work that makes her work all the more authoritative. Gardner makes her living by doing so; but it is becoming increasingly more difficult for critics to do so.

(pictured left) in The Guardian demonstrates a tenacity and dedication in seeking out the most interesting work that makes her work all the more authoritative. Gardner makes her living by doing so; but it is becoming increasingly more difficult for critics to do so.

When Edward Seckerson resigned a couple of years ago as chief classical music critic of The Independent, he revealed that he was being paid just £90 a review; that was down from the £150 he used to be paid. On the other hand, there is quite a lot of money sloshing around in the online world beyond the editorial floor; when Ariana Huffington sold The Huffington Post to AOL, it was sold for a staggering $315m — all for a site built on the free labour model of unpaid blogs.

In the last few years, New York has seen the elimination of the role of theatre critics on a number of leading publications – as Michael Riedel wryly noted in a column in the New York Post, “Being a member of the New York Drama Critics’ Circle these days is like being in a revival of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None.”

He was reporting the layoff there of the late Journal News critic Jacques le Sourd, who had served as critic for 35 years, and as le Sourd wrly observed, “My next assignment was on the Depression hits Broadway. I don’t have to do that story now. I’m living it.”

This situation has also been mirrored in LA, where a number of leading critics have lost their jobs, from the LA Weekly to the Daily News. But the theatre community there has far from welcomed this disturbing development, and the artistic directors of three of LA’s leading theatres, Gilbert Cates of the Geffen Playhouse, Sheldon Epps of the Pasadena Playhouse and Michael Ritchie of Center Theatre Group, wrote an eloquent joint letter decrying it.

As they say, “It may seem somewhat ironic that leaders of arts institutions would come out in favor of further criticism. It would be like fire hydrants getting together to come out in favor of more dogs. But, as artistic leaders who run three of the larger theater organizations in Los Angeles, we’ve recently become worried. Over the last few months there has been a conspicuous disappearance of arts writers and editors in our local papers… Criticism is always difficult to hear, especially if it comes from friends, relatives, acquaintances, neighbors, strangers, bystanders or casual observers. But it is even harder to bear when one realizes that criticism is being shared publicly with thousands of readers and may form the basis of their own opinion toward your work. Yet we depend on the voices of critics and arts reporters to help create a conversation with our community. If we let these voices slowly and quietly disappear, the consequences are simple and inevitable: fewer people will know about the productions, fewer people will purchase tickets, and eventually, fewer theaters will exist.”

So, to adapt the old adage, “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”, if a theatre production opens and there is no one to list or review it anymore, has it actually happened? Of course it has; but reviews act as a permanent record of an ephemeral art, and they also encourage people to attend and support it before it passes. We lose that at our peril. And artists are realising it, even if editors and proprietors aren’t.

In the last couple of years, the trees have started falling in the British forest with alarming frequency. The Independent on Sunday and Sunday Telegraph in turn both gave up having regular critical reviews; so has the daily Metro free sheet in London, while the print incarnation of Time Out, too, has gone free and shrunk, so it can only carry three or so reviews a week, though it has many more online.

As David Lan (left), the artistic director of the Young Vic, told The Stage in 2013 when his organisation won three of the nine Critics’ Circle Theatre Awards, “To receive these awards from critics is helpful. One of the things the critics do is create confidence in a piece of work. There are some other ways of creating that confidence – partly the reputation of the theatre and partly the reputation of the actors. Not many people think too much about the directors but they’ll also think about the writers. One of the ways you try and talk to your audience is say ‘it’s not too big a risk’ or ‘it’s worth taking a risk on’ and what the critics can do when they write about a show is create that confidence in it.”

As David Lan (left), the artistic director of the Young Vic, told The Stage in 2013 when his organisation won three of the nine Critics’ Circle Theatre Awards, “To receive these awards from critics is helpful. One of the things the critics do is create confidence in a piece of work. There are some other ways of creating that confidence – partly the reputation of the theatre and partly the reputation of the actors. Not many people think too much about the directors but they’ll also think about the writers. One of the ways you try and talk to your audience is say ‘it’s not too big a risk’ or ‘it’s worth taking a risk on’ and what the critics can do when they write about a show is create that confidence in it.”

Now its time, I think, to establish confidence in ourselves again. I’ve consciously stayed ahead of the game by adapting along the way to new things. My Stage blog is now long established – I’ve been writing it since 2005, so it has become not only an archive in itself but also a place that’s well known in the industry for taking up causes in. It sometimes gets me into trouble – I’ve had a few lawsuits, none of which have led anywhere, but it proves if nothing else that you’re being heard.

I’ve also now got my own personal website shentonstage.com (the one you are reading now!), where I post unique content as well as links to other content. The big problem here, of course, is time; finding time to update it regularly, when I’ve still got deadlines for paying jobs to meet. Fortunately, I’m an early riser — I’m sometimes up as early as 5am, simply to get the work done. You can’t be lazy in this job.

But I also consider myself extremely lucky — I love the theatre and I love being part of its active promotion.

As a freelance critic, I don’t belong to a single media outlet; and the good thing is that this has meant that I’ve been able to evolve my online identity in its own right. And part of that means embracing twitter, too — and not just having an account, but posting active commentary. Twitter is the ultimate democracy — people will only follow you if you have something to say, and they want to listen. But it’s not just a broadcast channel for me — it’s also a place of genuine interaction and sharing of opinions. I love the crisp exchanges that can take place there — though not some of the online abuse. Fortunately I don’t get too much of the latter.

Nobody pays you to tweet, of course, let alone to eat (though a few restaurants have offered a free meal sin exchange for a tweet, which I’ve politely declined). But it helps to build a readership and profile.

I’d say that Twitter is one of my most important outlets now — and certainly the most immediate in terms of reaching a readership instantly after I see a show. It’s a power I feel a lot of responsibility about using responsibly. ??But then that’s the case with every and any word I write, too. If, as I do, I believe that critics matter, then so do my words. So it’s important to think about their possible impact and reach.

And that’s even more so the case when you have built or are building the platform for their distribution yourself. There are hardly any jobs left in mainstream media and they are shrinking all the time; in fact, mainstream could soon become the minority media, and the mainstream is very likely to be you and your fellow bloggers.