Ring out the old and ring in the new: we’ve already seen some pretty major cultural shifts thanks to the last year, like the way cities are inhabited and used, that may make a return to the way things used to be impossible.

OK, I know I’m just one guy; but even I, a lifelong city dweller, from my native Johannesburg to the age of 16, then London ever since except for my three years at Cambridge, and with a foothold in New York as well, have decided next month to make a move with my husband to the countryside. As a friend of mine recently commented, New York is only the centre of New York; there is life beyond it.

And some overdue changes are coming to the theatre, too. We’ve already seen the cries for institutional change that were ignited by #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter. And of course it is the younger generation that is hungriest for change, and most eager for opportunities to claim the space that has been held, very tightly, by the older generation.

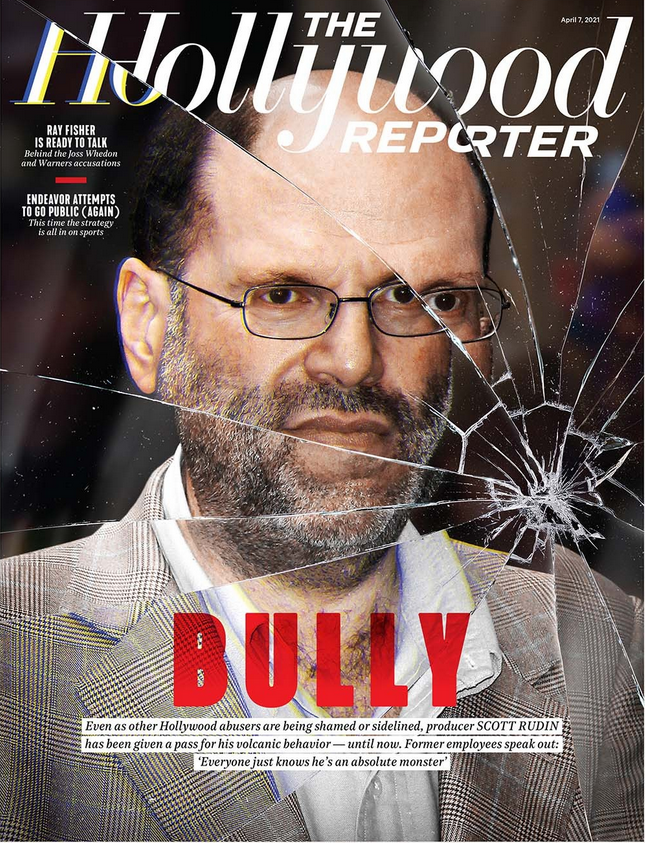

We’ve just seen the very precipitous fall from grace of Broadway’s single most prolific and powerful producer Scott Rudin, that I’ve already itemised in detail in various columns here over the last three weeks since the Hollywood Reporter first published a devastating expose of his bullying of his own staff, stretching back across over a quarter of a century, that included a trip to the emergency room being required by one assistant after Rudin had smashed a computer monitor onto his hand; we’ve also hear from the twin brother of a former assistant of his who committed suicide after working for him.

Following these sickening revelations, Rudin has retreated and stepped back from his day-to-day responsibility for his productions — including in London, where Sonia Friedman was his person on the ground and will now lead without him — as well as resigning from the Broadway League. It is not yet known what exactly all of this will mean; will he still be a silent partner in his shows, reaping the rewards of the productions, while not running them? As it is, however, he is unlikely to be able to negotiate for future shows from the position of overwhelming strength he has previously occupied; he had an informal ‘lock’ on at least a handful of prize Broadway houses every season for his shows in a sweetheart deal with Broadway’s most powerful landlord, the Shubert Organisation, that gave him automatic access to the Shubert, Booth, Schoenfeld and Golden Theatres, all along the same 45th Street block.

With him off the scene, this may enable other producers the opportunity to book those theatres instead.

And in London, there are similar murmurings of change on the horizon. Some of this may take a while to reach fruition, but three brand-new production companies have emerged in the last few weeks, and there’s some serious partnerships amongst them. At the beginning of the month, it was announced that a new transatlantic outfit called Wessex Grove — “set up by Benjamin Lowy and Emily Vaughan-Barratt in 2020 to produce and general manage innovative and exciting work of the highest quality in the West End, on Broadway, and worldwide”, according to the press release — have partnered with the Donmar Warehouse in a multi-year development deal to create new stage projects and invest in their life there.

Lowy previously ran a production company in New York that was a co-producer of the Broadway transfers of Jamie Lloyd’s West End production of Pinter’s Betrayal and the Public Theatre’s double-bill of two British one-act, one-actor, plays Seawall/A Life; while Vaughan-Barratt was a producer at Ambassador Theatre Group for eight years, including all the Jamie Lloyd Company shows that included Macbeth with James McAvoy and the aforementioned Betrayal.

In their press statement announcing their new partnership, Lowy and Vaughan-Barratt commented,

“Wessex Grove was founded on the principle of being led by great artists, and we are excited to collaborate with brilliant Artistic Director Michael Longhurst and Executive Director Henny Finch. Now more than ever, Wessex Grove is committed to supporting innovative artists and their works and the Donmar has always been at the forefront of creating, developing, and showcasing the best of British theatre. We hope to be able to give many of these productions a future life, and enable their work to reach wider audiences both here in the UK and across the world. Wessex Grove is proud to support the Donmar in their mission to change society for the better through excellent entertainment.”

(This is not, of course, the first time the Donmar has struck a first-look deal with a commercial producer; they previously had relationships with other producers when previous artistic and executive directors were at the helm).

And last week, another new theatre and film production company called Kindred Partners was launched by a powerhouse of partners, led by Adam Kenwright (formerly in charge of his own transatlantic advertising and marketing company AKA and then a senior executive at ATG Theatres) and Diane Borger (formerly executive director at the Royal Court and more recently at American Repertory Theatre), along with Amanda Murray, Chris Ryan, Claudia Brunning and Luke Johnson, all of them experts in their fields. (I knew Chris Ryan when he was commercial director at Encore Tickets, when I contributed to the website LondonTheatre.co.uk that they owned, but no longer do now that Encore is owned by TodayTix in New York, and the editor based there has decided on bringing in new voices, or at least old ones that aren’t me).

And last but not least, a new production company called S&S Theatre Productions was also recently launched by Caroline Underwood (now an independent agent representing British and American musical theatre writers, but formerly long-time head of Head of Standard Repertoire and Musicals at licensing house Warner/Chappell Music) and writer Warner Brown, together with producers Jenny Eastop, Kent Nicholson and the brilliant and innovative musical theatre writer Joshua Schmidt.

All of these, however, are already established career professionals; what of a younger, even hungrier generation? This is where Nica Burns has brilliantly come in. Long a promoter of young talent, from the days when she ran the Donmar Warehouse in the 1980s (before it became the producing theatre powerhouse that it now is) and founding Edinburgh’s premiere Comedy Awards (originally called the Perriers, after the then-sponsor), she is now Chief Executive and co-owner of the West End’s Nimax chain of six beautiful theatres, including three on Shaftesbury Avenue — the Lyric, Apollo and Palace.

The Palace, of course, is awaiting the return of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child; but meanwhile is available seven nights a week. Also currently without a full-time tenant is the Vaudeville, while the Lyric and Apollo will see the returns of Six and Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, but both are of course dark on one night a week.

So she’s invited 23 first-time West End producers (some of whom are pictured below with her, middle front) to book short runs, from one nighters to a week, at her venues, in a festival called Rising Stars. Last weekend she told The Observer,

“These talented young producers are people I have been watching who have had their careers held back for the last 12 months. So it seems a fantastic opportunity to give them a boost that will now actually put them ahead of where they might once have hoped to be now.”

As she also commented,

“Without producers, there are no shows. The public don’t always realise that, but if these enterprising producers are the future of the West End, it’s looking good.”

This is a real investment in theatre’s future, putting her theatres where her mouth is to allow these producers the opportunity to actually open a show in the West End — but without the need for the massive capitalisation and risk that a full run might require.

The sort of shows they are all producing — with significantly lower prices than most West End fare — may also be the sort that bring in new audiences, too. So it’s a win-win situation.

I am proud to play my own small role in nurturing the producers of the future — I sit on the bursary panel for Stage One, the West End’s own training scheme for aspiring producers that runs seminars and facilitates mentorships, and is able to offer small grants to fund their office expenses as they develop new projects. So I’ve seen the pitches that some younger producers have made, as they face an industry panel that comprises existing West End producers — and me! — to test out their viability.

I know that it must be intimidating for them to meet a critic face-to-face in this way; but it is also healthy, as one day I may be reviewing one of their shows, so it helps for them to meet a face behind the name.

And now thanks to Nica Burns, I’ll be seeing many of them in West End theatres, as well as the Off-West End ones I’ve already encountered most of them in already.