A new weekly diary column of theatre-related headlines

A PHOTOGRAPH THAT’S WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS (AND SEVERAL THOUSAND POUNDS)

Splashed across pages 25 and 26 of yesterday’s Guardian was a double page photo spread of Anything Goes, currently in previews at the Barbican Theatre ahead of an official opening next Wednesday (August 4). You couldn’t buy advertising like it; and yet the show has won this for the cost only of arranging a photoshoot — the picture was supplied by Ian West for PA.

Theatre photography is an often under-rated art; while productions almost always employ a dedicated photographer to secure promotional, press and display photography, even more unsung are those freelancers who turn up for a show’s open photocall, where they are invited to photograph a much more limited range of set-up scenes. And since they are all taking essentially the same picture, there isn’t much to choose between them. So no wonder that newspapers now generally rely on the production hand-outs, for which they don’t have to pay a fee either. This has made theatre imagery for productions pretty generic; the same shots, or variations of them with different cropping, will be carried everywhere from WhatsOnStage to The Guardian.

So it’s lovely to see a theatre photograph making a splash in every sense, that hasn’t come from an established brand-name theatre photographer, of which there are an increasingly diminishing number anyway. My good friend Bob Workman recently retired; still working at the coalface are such legends as Nobby Clark and Tristram Kenton.

I’ve long said that the profession may miss theatre critics when we’re gone, but I’m beginning to fear that we’ll miss theatre photographers even more. There are so few left.

CRITICS PLAY CRITICS AND GET REVIEWED….

Yesterday, The Guardian reviewed one of its own — Michael Billington, playing a critic himself in a zoom production of the 1852 play Masks and Faces.

As Mark Fisher noted in his review, “Victor Kiam liked his shavers so much he bought the company Remington. The Guardian former chief theatre critic Michael Billington liked Masks and Faces so much he ended up in it. During his five-decade stint at the Guardian, the critic praised this 1852 comedy by Charles Reade and Tom Taylor in a “surprising revival” at London’s Finborough theatre. “I particularly liked the two critics, Snarl and Soaper,” he wrote, little knowing he’d one day land the part of Snarl opposite fellow critic Fiona Mountford as Soaper in a remotely recorded YouTube reading” (pictured below).

As for their performances, Fisher only says this: ” As for the two ingenues, I won’t comment on their future stage careers, but I will say Mountford beats Billington at the singing.”

THEATRICAL LEADERSHIP: BEHIND THE SCENES AT THE RSC

Once upon a time theatres were primarily run by actor-managers. Up to and including Laurence Olivier, who was the first artistic director of what became the National Theatre, it was actors who led from the front. But since he stepped down nearly fifty years ago, in 1973, he’s been succeeded only by directors (though the current incumbent Rufus Norris was a former actor).

But old habits die hard, and every now and then a working actor will try to re-establish the tradition. The closest we have to a successful transition is Daniel Evans, who is now at the helm of Chichester Festival Theatre (where his current production of South Pacific shows a director at the peak of his game), but has continued to perform a bit. And at the Globe, Michelle Terry is about to appear on its stage in its new production of Twelfth Night.

And during Peter Hall’s tenure in charge of the National the mid-1980s, Ian McKellen and Edward Petherbridge were put in charge of a company of actors that produced three plays, one in each of the NT’s auditoria; with half of a double bill in the Olivier directed by Sheila Hancock, thus making her the first woman director to work on the Olivier stage.

More recently — and it turns out more notoriously — American screen star Kevin Spacey took charge of the Old Vic for a mostly successful decade, but that legacy has been overshadowed by the accusations made of his inappropriate behaviour with young male actors and other theatre workers during his tenure.

Theatre is full of more ‘What Ifs’ of ambitions that are never realised. When Nick Hytner was stepping down from running the NT, Kenneth Branagh had been approached as a possible successor, as Anthony Hopkins revealed at the time: “He wrote me an email and told me he’d been offered the directorship. I said do it, because he’s the only actor who could replace Olivier today. I told him he must accept. You see, Ken has got the teeth and the guts to do it.”

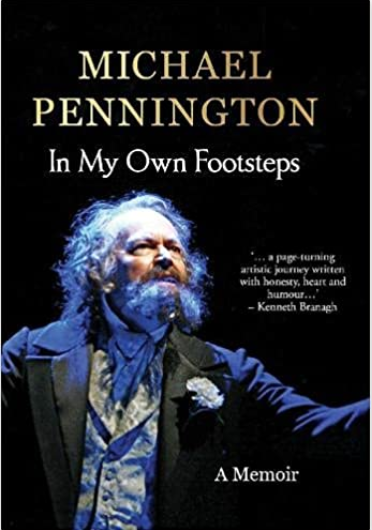

And in his new memoir ‘In My Own Footsteps’, available on Amazon here, veteran actor Michael Pennington reveals in fascinating detail his attempt to secure the artistic directorship of the RSC, after Adrian Noble stepped down from the job in 2002, in unseemly haste shortly after directing Chitty Bang Bang in the West End. Pennington ended up on a short-list of four: Michael Boyd (who would actually get the job), Greg Doran (who would get his turn, in turn, after Boyd), and a joint application from director John Caird and Simon Russell Beale.

All of this was taking place against the backdrop of a plan being advanced by the company to either entirely demolish or re-purpose its Stratford-upon-Avon main house. In advance of his formal interview, he details, indiscreetly, meeting the RSC’s then-chair Lord (Bob) Alexander of Weedon, and the RSC’s principal benefactor Lady Susie Sainsbury (whom he writes has made an astounding financial contribution to the RSC, currently standing at over £26 million and placing her in the ranks of the UK’s greatest cultural philanthropists”).

But something disconcerting happens on the way to the forum — and he reports that “both she and Bob seemed a bit distracted, and I felt simultaneously like their initiated favourite and an interloper. All that they were doing something unorthodox by meeting in me in advance like this. Then things took a surprising turn. Both asked me if I thought the list of questions he’s prepared for the forthcoming big interview covered the ground; in other words, I was to approve my own cross-examination.”

Such cronyism, as we are constantly reminded by the daily machinations (and serial malfunctions) of the currently Conservative government, are the way things are done in the top echelons of British society, and theatre is no exception.

But theatre is also, of course, powerfully powered by gossip, too, and Pennington is full of this, too. “As we summed up, the unspoken form of fury with Adrian [Noble] (but was it real or assumed?) for his wilful defection, for his ‘bullying’, mainly because it cause the two of them to miss the first night of Antony and Cleopatra (though they pretended afterwards they’d been there), because they were having to find an urgent way overnight to announce his sudden resignation to the press. We were well behind discretion here, and I wasn’t even sure I sympathised; even if I agreed, I felt instinctively protective of him him as a colleague.”

It’s wonderful getting insights into the behind-the-scenes processes of such a important appointment, but also of the personal as well as the political. He reveals, “On 27th June, with relief, I had dinner with my dearest of friends, John Shrapnel. Since keeping secrets his fun, I enjoyed his categorical view that Greg Doran would get the RSC job, there was no alternative. I nodded, both wisely and dishonesty. The next morning, however, I broke the rule and told all the above to Annie Firbank, an equally old friend, on the phone.” And she was much more enthusiastic: she “saw excitedly that it might even happen.”

It doesn’t, of course; but there’s as much fascination in the failure of his attempt as we cannot now know what he would have brought to the company. Suffice it to say that Michael Boyd turned out be both a seriously safe pair of hands, whose own History cycle was one of the RSC’s major triumphs of the century so far, and also presided over the RSC transformation of its Stratford-upon-Avon HQ with serious skill (along with executive director Vikki Heywood). And unlike Adrian Noble, he never once chased commercial success on his own account (though saw the RSC score a major success for director Matthew Warchus and the company with Matilda).